Lancaster History

The history of Lancaster and specially selected photographs

Lancaster has a long and rich history. That history is mainly about people: those who visited and those who stayed, those in business and commerce and those who laboured in businesses, honest and upright people and people who committed a variety of crimes, those who came to learn and those who came to teach.

Some of the first people to visit Lancaster were the Romans. It was about AD 70 when the first Roman commander would have looked out on the scene from the top of the hill where the castle now stands. Over the following years, he and his successors would see change to the town; the Roman fort would be built, and maybe there are more Roman buildings now hidden under ground below the priory church and nearby. Below, near where the bus station stands, he would see the Roman ships at the port on the River Lune, which then followed a different course.

The Roman fort was not a major fort, but an auxiliary one; it was built on a drumlin, or ridge, left by a retreating glacier at the end of the last ice age, and stood above the lowest crossing point of the River Lune. One place where the river may have been crossed at that time is Scale Ford, below Carlisle Bridge; the other would be somewhere near the Millennium Bridge or Greyhound Bridge. The Roman name of the fort is not known, but the name Lancaster itself is derived from the river name, 'Lune' or 'Loyne', and 'castrum', the Roman for 'camp'.

If he left his fort by the east gate, the Roman commander would pass through the gate and follow the road down what is Church Street today, which in his day was the ‘vicus’ or civilian settlement. There, he and his men would be able to trade with the local people. At the end of that road he would be able to turn right along another road, now Cheapside, formerly Pudding Lane and Butchers Lane. At the end of the road there would probably be a wall, and beyond it he would see the graveyard - the Romans buried their dead outside town walls. Various artefacts have been found here during archaeological digs over the years.

By the end of the Romans’ time here, Lancaster had become Christian, and it is believed that there was a church around where St Mary's church, the priory church, now stands. Beyond the present church are the remains of the Roman bath-house, which are still to be seen in the field to the right when walking from the castle past the church and down to the river. To the left, the shape of the land shows that it was part of the old fort - three were built on the site over the years.

Following the Norman Conquest, the Normans compiled the Domesday Book in 1086, a survey of England for taxation purposes: in it Lancaster is listed two parts, Lancaster and Church Lancaster. It was the Normans who made the Forest of Bowland a royal forest or hunting ground, and subject to very strict forest laws.

Roger of Poitu, a relative of William the Conqueror, was given lands covering most of Lancashire, and in around 1093 he built himself a stone castle, no trace of which survives. In 1094 he founded the priory on the hill by the old Roman fort. Monks came over from his home town of Seez in Normandy to run it. Because Roger was granted his estates, which were known as the Honour of Lancaster, directly from King William Rufus, he was a very powerful man, and he held his own court to dispense justice at least once a year. At those courts, the freeholders of his manors could not sit, but had to stand bareheaded. It was at this time that the county of Lancashire was formed, and Lancaster became the county town.

In 1199 Lancaster received its first royal charter from King John. This changed what had been a village to a borough, and gave Lancaster some special privileges, including permission to take wood from the forest of Quernmore for building; it also gave the burgesses the right to graze their animals in the forest as far from the town as they could return home within the day.

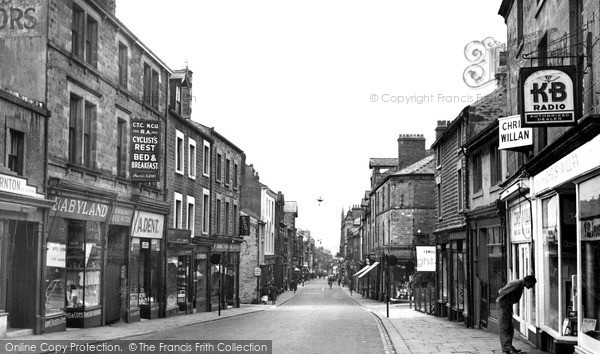

The main houses lining Lancaster's streets in medieval times each had its own strip of land, known as burgage plots. (The word 'burgage' relates to tenures of land in towns held for the king or another lord). Sometimes there were passageways between the plots. This can still be seen in Penny Street, where the plots go back to Mary Street, with an ancient passage remaining as a right of way by the Halifax. There were once attempts made to close the passage, but a Lancaster businessman fought for its retention.

Lancaster Castle was, in theory, the residence of the lord of the Honour of Lancaster. Only parts of the old building remain: the principal features are the Norman keep and the much altered Adrian's Tower (also known as Hadrian's Tower). Above the gateway into Lancaster Castle is a statue of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1340-99). John of Gaunt visited Lancaster in 1385 and 1393 for a total of nine days, and they were the only times he came in his life. It is very unlikely that his horse cast the original of the shoe in the pavement at Horse Shoe Corner – the shoe is more likely to have originally announced the coming of a horse fair. John of Gaunt's son Henry Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV, built the impressive gatehouse of the castle around 1400, and to a large extent it took over the role of the keep. It is still the main entrance. It was Henry's estates that became the Duchy of Lancaster, which have belonged to the Crown ever since.

in 1362 Lancaster was made the seat of the assizes and the 'Principal Town of the said County', and so it assumed its judicial importance that continues today; courts are still held in the castle.

Lancaster itself did not particularly take sides during the Civil Wars, but the town was of strategic importance with its castle and also its position on a major north-south route, together with the crossing of the Lune. It also had great symbolic value as the county town. It is odd that although there were Royalist supporters further up the Lune valley, neither the castle nor the town were garrisoned by them in 1642. As a result, in February 1643 a company under sergeant-major Birch came up from Preston and took the surrender of the castle for the Parliamentarians.

This was not the end of the Royalist cause. The Earl of Derby then decided it was important that his forces should retake Lancaster; he set out from Wigan on 13 March, possibly having decided to do so because of the wreck of a Spanish vessel off Rossall Point in the Fylde - its 22 cannon had been taken to Lancaster Castle. On the way to Lancaster he added to his numbers by gaining troops from the Fylde. He arrived on 18 March, entering the 'Towne of Lancaster several waies' and meeting very little resistance, for the Parliamentary troops had retreated into the security of the castle. As a result, the town was open to plunder and burning. Penny Street in particular suffered, its timber and thatch buildings soon being set ablaze, the garrison having abandoned them to their fate. It is estimated that ninety premises were lost; in 1645 Parliament made a grant of £8,000 as compensation for them, but with strings attached. Later in the war, a 'rude company of Yorkshire Troopers', whom even the Parliamentarians admitted were a problem, garrisoned the castle. After the Civil Wars it was decided to demolish the castle so that it could not be garrisoned, but to retain those parts used for the courts and the prison. This left the gatehouse and the buildings on the south and west sides.

Lancaster was under the head-port of Chester until 1732, and its officers were appointed as deputies of those in Chester. The original Custom House was above the old bridge, and in 1732 a new Custom House was built below the bridge. By the 1740s, the town was desperately in need of a proper quay for its shipping to load and unload, and in 1749 the Lancaster Port Commissioners were established by an Act of Parliament. A year later the construction of St George's Quay was begun - a wall was built at the low tide line and the space behind was filled in. Houses, shops and warehouses were built; the older warehouses were of three storeys, rising to five storeys for the newer ones.

A space was left between the warehouses, presumably in anticipation of a new Custom House. This was built in 1762 to Richard Gillow's design. At ground level was the Weigh House, where goods were weighed before being placed in bonded warehouses. Boatmen and others would wait here when on call. The first floor could not be reached from indoors, but only by using the outside steps. These led straight into the Long Room, where the clerks sat and where the business with the ships' masters and the merchants were transacted. Beside it was the Collector's office for collecting the dues, together with other offices.

Lancaster became wealthy in Georgian times, resulting in the erection of fine Georgian buildings, many of which still stand today. Local stone was readily available, in particular where polished freestone was needed – this was sandstone rubbed to a flat finish. Mainly, this stone came from Lancaster Moor, where there were a number of quarries in the 18th century, including Scotforth and Ellel.

The old bridge over the Lune was reached down Bridge Lane, which began by Covell Cross at the top of Church Street, and passed by the Three Mariners – at this point there is the only remaining part of the original road to St George's Quay. Particularly since 1745, when the parapets had been demolished, the bridge had become unsafe, and there were a number of accidents. On one occasion a woman was leading a horse and cart full of coal across the bridge when the linchpin on one of the wheels broke and they all fell over the side of the bridge. The horse was killed, the cart smashed and the woman 'a good deal hurt'. A new bridge giving better access to the town needed to be built, and on a route that was less congested than having to cross over the Quay to reach it. The architect Thomas Harrison had designed bridges in Rome, and he won the competition for the new Skerton Bridge. He designed a bridge with five arches, but with a level roadway, the first in this country - previous bridges had been bowed at the centre. Another special feature is the five relieving arches to increase the water flow at times of heavy flooding. Harrison's bridge cost £14,000, and was opened in October 1788.

Another of Harrison's works was the rebuilding of Lancaster Castle; he was commissioned as architect for the work in 1788. It is mostly his work that we see today. He altered Hadrian's Tower, removing the ceilings and raising it to its present height. His Grand Jury Room is perfectly round, and it is believed that Harrison insisted that the two doors be constructed with a curve to conform to this. His work also included the magnificent Shire Hall, the Crown Court and the barristers' rooms. He was responsible for part of the prison, and most of the exterior walling – he made the castle larger than it was in medieval times. The Grand Jury Room and the courts were largely furnished by Gillow’s, and are a tribute to their craftsmen.

By the late 18th century many other towns had become linked to each other by canal, but Lancaster was out on a limb. A canal between Kendal, Lancaster, Preston and beyond had been discussed several times over the years, and surveys had been made. By 1791 patience was running out, and on 4 June thirty Lancaster merchants and traders petitioned the mayor to convene a public meeting to consider the making of a canal linking Lancaster to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Only four days later, on 8 June, it was resolved to promote a canal, and a subscription list was started.

The Canal Committee was not satisfied with the earlier lines surveyed, and in October 1791 they appointed John Rennie to survey a route. A broad canal was needed to carry larger and longer boats than those on some other canals. This would enable coal to be carried from south Lancashire through to Kendal, and large quantities of limestone in the opposite direction. John Rennie’s survey included a deep cutting to the south of Lancaster, and a lower crossing of the Lune than in the earlier surveys. The next stage was another meeting in the town hall on 7 February 1792, when it was unanimously resolved that an Act of Parliament be obtained to build the Lancaster Canal, running from West Houghton in the south of the county through to Kendal. The construction of the canal started in 1793, and went ahead not without its problems. It was not until January 1794 that works started on John Rennie's Lune aqueduct. The original specifications of the aqueduct are signed by John Rennie and by Alexander Stevens from Edinburgh. Stevens and his son were architects from Edinburgh, and responsible for the building of the bridge.

John Rennie's Lune aqueduct is 600 feet long. Piles about 20 feet long were driven into the bed of the river to make a foundation for the piers, which go down to 20 feet below Skerton Weir. The piers alone cost just over £14,790. Rennie wanted to build the aqueduct of brick, but the committee would have none of that, for Lancaster was built in stone. This greatly increased the costs, so that there was too little money to cross the River Ribble; this resulted in there being no link by water between the Ribble and the main canal system until the opening of the Millennium Ribble Link in July 2002. The original estimate for building the aqueduct was £18,618 16s, but the final total was £48,320 18s 10d.

The Lancaster Canal was formerly opened between Preston and Tewitfield on 22 November 1797.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Lancaster History in Photos

More Lancaster PhotosMore Lancaster history

What you are reading here about Lancaster are excerpts from our book Lancaster - A History and Celebration by Robert Swain, just one of our A History & Celebration books.