Northampton History

The history of Northampton and specially selected photographs

Northampton prospered as a river port and trading centre in Anglo-Saxon times, despite being burnt in 1010 by a Danish army under the command of one Thorkil, and burnt again in 1065 by the rebellious northern earls Edwin and Morcar as part of their revolt against the then Earl of Northumbria, Tostig.

Northampton’s physical situation, where the River Nene cuts through the limestone ridge and turns northwards along its west edge, provided an ideal defensive position, as well as the control over a river crossing where key routes converged from all directions. After the Norman Conquest, the strategic value of the town, virtually in the centre of the kingdom, was recognised by the building of a castle.

The building of Northampton’s Norman castle was undertaken by the town’s overlord, Simon de Senlis (or St Lis), about 1086. It was probably originally an earth and timber stockaded construction, which was rebuilt in stone over the next two centuries. The castle was taken over by the king in 1130, and was used as an occasional royal residence. Northampton’s castle is now no longer to be seen, for it suffered not one but two cruel fates: the first was after the Civil War and the Commonwealth, for in 1662 the newly-restored Charles II took vengeance on the pro-Parliamentarian town by ordering the castle to be slighted, so that it would not be of any future military use to rebels against the throne. A fair amount of the castle survived this treatment, only to succumb in the 19th century when the railway station was built across its site in 1879. A plaque commemorates the castle in Chalk Lane, which runs curving north along the course of the castle’s eastern moat.

Medieval Northampton stretched eastwards from the river and castle, with Market Square as its focus. The medieval town walls, demolished as well as the castle at the orders of Charles II in 1662, enclosed about 245 acres (98 hectares), with St Giles’s Church near the east gate and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre towards the north gate.

Northampton has a long civic history which pre-dates the first recorded charter in 1189 (during the reign of Richard I, ‘the Lionheart’) when the burgesses or merchants paid 200 marks to hold their town ‘in chief’, that is, direct from the king. By the time of William the Conqueror’s great survey of the wealth of his new lands in 1086 that came to be known as the Domesday Book, there were 87 royal burgesses holding their tenements direct from the king, as well as 219 holding theirs from other lords, so the town was already large and had its own reeve and bailiffs. In 1215 King John authorised the appointment of William Tilly as the town’s first mayor. He also ordered that ‘twelve of the better and more discreet’ residents of the town should join him as a council to assist in the running of the town. The importance of Northampton at this time is underlined by the fact that London, York and King’s Lynn were the only other towns in England which had mayors by this date.

There were various monasteries and friaries in medieval Northampton. These included a wealthy Cluniac monastery, St Andrew’s Priory, founded by Simon de Senlis around 1100. Although it is long gone, it is commemorated in the names St Andrew’s Street, off Broad Street, and Priory Street. There was also a house of Augustinian canons, St James’s Abbey, which stood west of the river, which is commemorated in the area of Northampton known as St James. There were three friaries: a Franciscan friary founded in 1226 is now remembered in the name of Greyfriars Street near the bus station; a Blackfriars (Dominican) friary, founded around 1230, and sited near Horse Market; and a Whitefriars (Carmelite) friary, founded in 1271.

Markets and fairs were a major element in medieval Northampton’s trading and manufacturing economy. The first reference to a fair is to one which was held c1180 on All Saints’ Day in All Saints’ Church and churchyard. In 1235 the fair moved to a waste area north of the church. This waste became the present spacious Market Square, described in 1712 as ‘look’t upon as the finest in Europe; a fair spacious open place’. The fair grew into an annual event which lasted all of November. The town also acquired various weekly markets, with a charter of 1599 confirming Wednesday, Friday and Saturday as market days. Street names in the town give a fair indication of the trades and market centres in the town, for example, Corn Hill, Malt Hill, Mercers Row, Sheep Street and Horse Fair. Market tolls were a major source of the town’s income, and market rights were jealously protected, hence the numerous charters obtained over the centuries.

Northampton witnessed many important events during the Middle Ages. It held both the forerunner of parliament (which was more of a great royal council) and full parliaments, before these finally settled in the royal palace of Westminster after following the king around the country. The royal council first met in Northampton from King Stephen’s reign (1135-54). The first parliament attended by burgesses or merchants, the forerunners of the later members of the House of Commons, was held at Northampton in 1179. After the Barons’ Wars of the 1260s, when the town was besieged and captured from Simon de Montfort, the barons’ leader, several parliaments were held here, including the notorious one of 1380 when the first poll tax was passed. This nationally-hated measure provoked the Peasants’ Revolt of the following year.

During Henry II’s reign the town was host to the council that arraigned Thomas a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry’s one-time friend and chancellor. Thomas a Becket was a great disappointment to the king, who had hoped that he would be a willing ally in bringing the Church under royal control. He was wrong, and Becket was arraigned in Northampton Castle in 1164. After his trial for treason at Northampton in 1164, Thomas a Becket escaped from St Andrew’s Priory. By an ancient tradition, he is supposed to have stopped at a well on the Bedford Road for a drink before continuing on his way, eventually taking ship for France and exile. He later returned to England, and was famously martyred in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170, when he was murdered by four knights who may have taken Henry II’s angry outburst ‘Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest!’ a little too literally - or so the king later claimed. The well, marked on the 1610 John Speed map of Northampton, had its well-house rebuilt by the corporation in 1843 in Gothic style.

The town suffered a devastating Great Fire in 1675; this disaster destroyed much of the historic heart of the old town, and left relatively few buildings standing that date from before the fire.

Three of Northampton’s medieval churches survived the Great Fire of Northampton of 1675, and two of them, Holy Sepulchre and St Peter’s, are of particular interest. Holy Sepulchre, in the north of the walled town, has a circular nave whose plan copies that of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem; it is a direct link with the Crusades, when the Holy Land was the scene of campaigns by knights from western Europe. Simon de Senlis, Earl of Northampton, had himself been a crusader, and founded this most unusual church upon his return from Palestine, at some time between 1100 and 1112. There are very few round churches in England. The church was enlarged with a fine 13th-century chancel and later chapels to its east, and a 14th-century tower and spire added to its west. Equally astonishing, for its sculptural richness, is St Peter’s Church, near the castle site; it dates from around 1170 (built by the grandson of Simon de Senlis, another Simon), and is built in the ornate Norman style. The stone carving in this church exudes an almost barbaric air: the capitals are full of curious foliage inhabited by mythical winged creatures, writhing figures and animals, and the arches are a profusion of geometric decoration. The third surviving medieval church is St Giles’s, at the east end of the town, which has a Norman crossing tower with the rest later medieval.

Much of the medieval All Saints’ Church was destroyed in the town fire of 1675, though the tower survives from this earlier building, as does the chancel crypt. The church was rebuilt in the classical style, probably designed by Henry Bell from King’s Lynn, and was completed in 1680. The medieval tower, formerly a crossing tower, was retained, and a forecourt or square was created in front of the portico on the site of the medieval nave. The cupola on the tower was added in 1704.

For many centuries boot- and shoe-making were major industries of Northamptonshire. This was influenced by two major factors - lush grassland and extensive forests. The bark of oak trees provided the tanning materials, and the flocks and herds grazing on the Northamptonshire grassland provided the leather. By the early 18th century the town of Northampton had already become a noted supplier of footwear to the army, as well as to civilians and the American colonies. Daniel Defoe commented on Northampton’s famous footwear in his ‘Complete English Tradesman’, published in 1726, when he listed all the English towns which contributed to the making of a suit of clothes:

‘If his coat be of woollen-cloth, he has that from Yorkshire; the lining is shalloon from Berkshire; the waistcoat is of callamanco from Norwich; the breeches of a strong drugget from Devizes, Wiltshire; the stockings being of yarn from Westmorland; the hat is a felt from Leicester; the gloves of leather from Somersetshire; the shoes from Northampton; the buttons from Macclesfield in Cheshire, or, if they are of metal, they come from Birmingham, or Warwickshire; his garters from Manchester; his shirt of home-made linen of Lancashire, or Scotland’.

Brabner’s Gazetteer of England and Wales listed the industries of Northampton in 1895, showing that boot- and shoe-making and the associated trades were still one of the mainstays of Northampton’s economy: ‘Immense quantities of boots and shoes are still made for the supply of the army, the London market and for exportation. A large trade is also carried on in the tanning and currying of leather. The breweries of Northampton are among the largest in the kingdom, and there are several important maltings and large flour mills. There are also some extensive iron foundries, and bricks and tiles are made to a considerable extent around the town’.

In 1965 it was announced in Parliament that Northampton was to become one of the ‘New Towns’ to accommodate London’s overspill, and in 1968 the Northampton Development Corporation was established. A Master Plan was drawn up and work started on new housing and industrial estates and centres, initially to the east and south of the old town; the aim was to more than double Northampton’s population on 120,000 by 1981. The nearby M1 put the expanding town at the hub of the national road network, with direct links to London, Birmingham and the north, and Northampton now has a population of over 200,000.

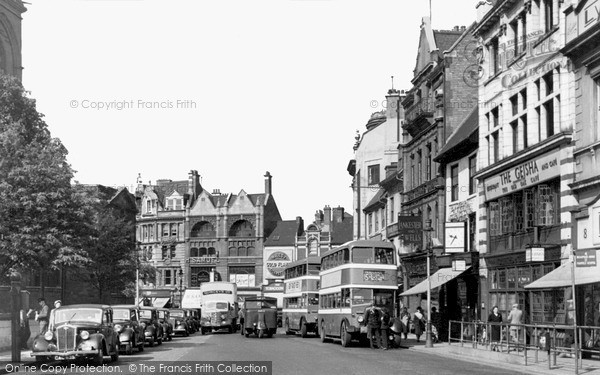

In the last decades of the 20th century the old town centre of Northampton was subject to much redevelopment, in common with the rest of the country, when many old buildings were demolished and town centres were redeveloped. Northampton before ‘modernisation’ was a town in which small brick factory buildings and foundries co-existed with shop, offices and houses, and smells wafted over the town from the tanneries and breweries. This was before much of the town’s fabric surrendered to the motorcar and lorry, and before the inner ring road turned the old Horse Market, Broad Street and Gas Street into a dual carriageway cutting Mare Fair off from the town centre. Fortunately, the town had enough density of historic buildings to weather the storm with much of its character intact, and enough of the town’s pre-1960 fabric remains to make the town centre worthy of inspection. There is no doubt that moves such as the pedestrianisation of much of Abington Street and the retention of Market Square as a real market place have helped to give the town back to the people.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Northampton History in Photos

More Northampton PhotosMore Northampton history

What you are reading here about Northampton are excerpts from our book Northampton Town and City Memories by Martin Andrew, just one of our Town & City Memories books.