Bournemouth History

The history of Bournemouth and specially selected photographs

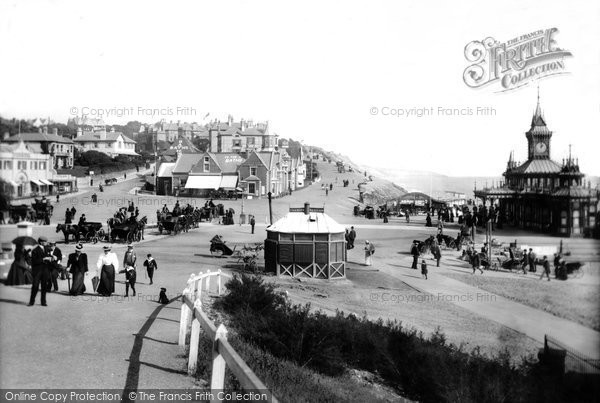

Standing on Bournemouth sea front on a summer's day, when it is most alive with the sights and sounds of thousands of tourists and motor traffic, it is hard to grasp that less than two hundred years ago there was little to be seen in this spot except miles of wild heathland, and no sounds but the cry of the birds and the murmur of the sea.

For Bournemouth is a town of recent origin. Had Mr Lewis Tregonwell decided to build his holiday home elsewhere in 1810, there is a possibility that the Bournemouth we know today might never have existed. It was to take a further eighty years before this town even approached its heyday as a family seaside resort.

If anywhere should have become a resort it was neighbouring Mudeford, patronised as it was by regency notables such as Sir Walter Scott, Southey and Coleridge. But the flow of history, perhaps fortunately, passed Mudeford by. No doubt because of the iron-handed restrictions of the landowner of that time Sir George Rose who barely tolerated visitors unless they behaved with exceptional propriety.

No doubt seeking peace and quiet, other wealthy gentlemen followed Tregonwell's example; but even by 1841 there were still only some thirty houses scattered around the heathland. It was probably not until the arrival of the railway in 1870 that Bournemouth finally opened its doors to the mass-invasion of tourists, many of whom subsequently took up residence. But that is not to say that a significant minority had not already discovered its considerable charms.

For many years the town catered for what the Victorians called "the better class of visitor"; few others probably came, given the town's distance from the growing urban settlements. Local villagers and agricultural labourers would simply have never been able to afford the prices at the original hotels and boarding houses.Those who wandered into Bournemouth in pursuit of their trade must have been bewildered by the fineness and exclusivity of the strange new settlement.

Unlike resorts which had grown up around older industries such as fishing and merchant shipping, Bournemouth dedicated itself from the start as a venue for holiday pleasures, spurred on by the enterprising Sir George Gervis, a wealthy landowner who had arrived soon after Tregonwell. Under his guidance the first real hotels began to appear, a library and reading room were established, and the first villas - available for hire at four guineas a week - began to line the clifftops. An early travel writer lauded his approval: "the magic hand of enterprise has converted the silent and unfrequented vale into the gay resort of fashion, and the favoured retreat of the invalid".

But the whole project might still have foundered had it not been for the timely arrival of the famous Dr Granville, connoisseur of favoured watering places and eventual author of the standard Victorian guide to their health benefits Spas of England and Principal Sea-Bathing Places. Bournemouth's wily planners gave a dinner in the good doctor's honour, seeking his help in keeping the momentum going. Granville responded magnificently, announcing that the resort was superb for the treatment of consumption, but urging the gathered dignitaries not to allow the burgeoning new town to go downmarket.

On his advice the flowing waters of the Bourne Stream were captured and transformed into the tamer, decorative water feature we see today. The wilder parts of the vale were turned into gardens and walkways. Villas sprung up along the slopes of the hills and the clifftops, each one standing in its own health-giving grounds - just as the doctor ordered. Grateful valetudinarians, but only those who could afford to come, flooded into the area. The results probably were conducive to better health even if, as the consumptive Robert Louis Stevenson put it some years later, life there "was as monotonous as a weevil's in a biscuit".

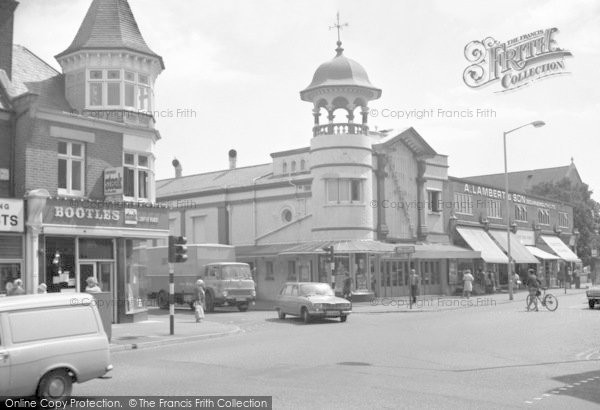

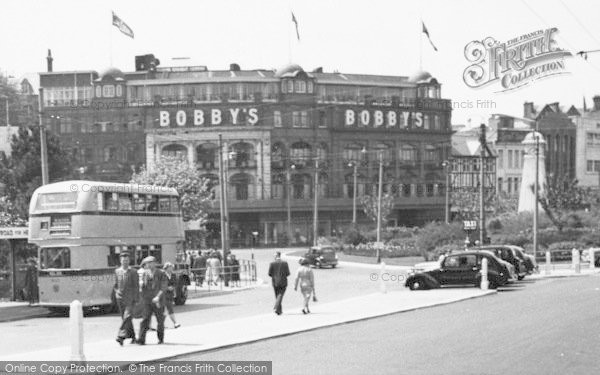

As time went by and social attitudes changed people arrived in Bournemouth for the sake of enjoyment alone. A wider choice of hotels and boarding houses became available. A pier was constructed and a theatre and beach entertainments provided. To cater for the huge increase in population and the massive influx of tourists a huge variety of shops opened. Bournemouth became something in character to what we see today.

This is not to say it plunged rapidly downmarket. It continued to attract very well-heeled visitors and hotel advertisements of the 1890s boasted the patronage of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), the Empress of Austria, the King of the Belgians, Empress Eugenie - "and all the leading Personages visiting Bournemouth".

Happily, a wider section of society enjoys Bournemouth today, for leaving aside its own delights and fascinating social history, it could have been tailor-made as a touring centre for Dorset and Hampshire. The new City of Bournemouth, together with Christchurch and Poole, makes up the largest urban mass on the Dorset coast.

Despite some modern buildings and the vast sprawl of its suburbs, this is still essentially a resort that Gervis and Granville would recognise - though the snobbish doctor would probably not approve of the influx of 'ordinary people' who come back year after year to enjoy the long miles of beaches or linger in the flower-filled gardens.

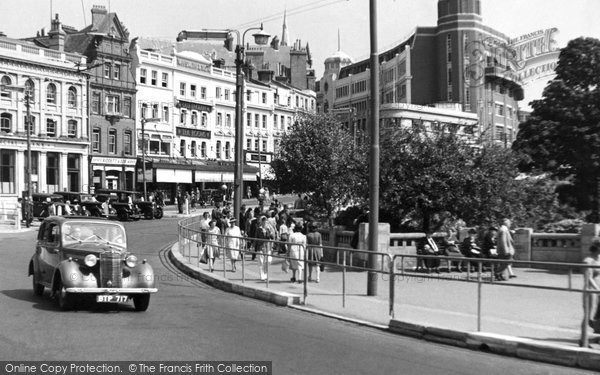

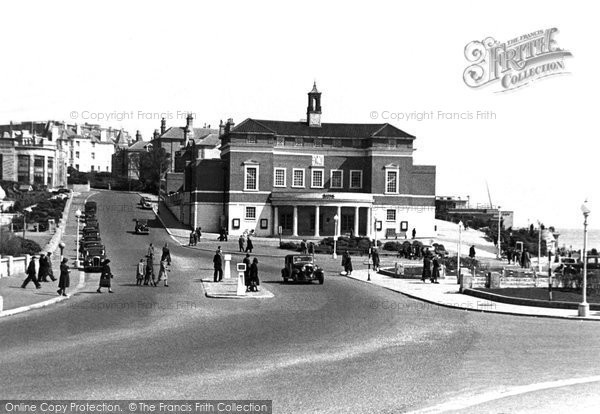

Bournemouth is a part of the holiday memories of millions of Britons and travellers from further afield, a proud city and now a university town. The photographs of Bournemouth in The Francis Frith Collection, taken at important staging posts in its history, give us some idea of how the transformation from wild heathland to bustling resort came about.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Bournemouth History in Photos

More Bournemouth PhotosMore Bournemouth history

What you are reading here about Bournemouth are excerpts from our book Bournemouth Photographic Memories by John Bainbridge, just one of our Photographic Memories books.