Brighton History

The history of Brighton and specially selected photographs

Old Brighton was a coastal fishing village bounded by West Street, East Street and North Street, that area of town now known as 'the lanes'. There was once a South Street, and indeed a whole 'lower town' on the beach, but they were claimed by the sea in the early 18th century. To the east of East Street, a marshy valley, the Steine (pronounced 'Steen') with a little stream, the Wellesbourne, ran down to the coast. Here fishermen would spread their nets to dry, and here was the farmhouse where the Prince Regent (later King George IV) stayed. He took a liking to the place, and ended up building the Royal Pavilion, Brighton's best known building, which is now listed Grade 1.

Brighton was a 'spa' town before the Prince arrived, thanks to a treatise on the use of sea water by Dr Russell of Lewes, published in 1754. Royal patronage ensured that it became the fashionable place to 'take the waters', and the town developed apace. Up went the Regency terraces, squares and villas for which Brighton is famous, a style of building which continued here well into the Victorian era. The Steine became the place to 'promenade', and various improvements took place with the building of the North and South Parades. In 1823 the Steine was enclosed with tall iron fencing, and the following year it was provided with gas lights.

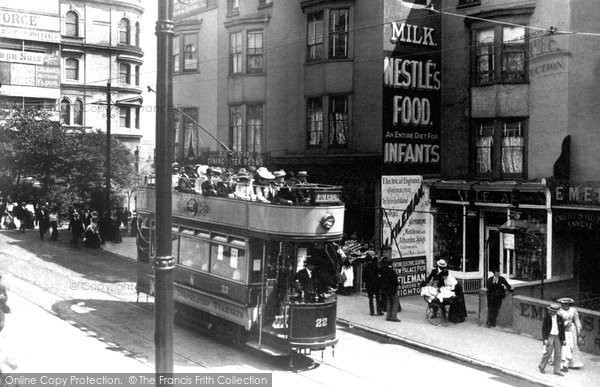

When the railway arrived in Brighton in 1841 it brought with it a new kind of visitor, the 'tripper'; the town grew greatly in size, filling up with hotels, boarding houses, cafes, restaurants and theatres. North Street and East Street, the principal shopping streets, bustled with activity. Brighton was also famed for its schools, which took advantage of Brighton's reputation as a health-giving place; they found perfect accommodation in large Regency villas.

Brighton's parish church, St Peter's, was built in the 1820s at Richmond Green, just north of the Steine, and designated as the parish church in 1873. It was originally a chapel-of-ease to the old parish church of St Nicholas, set up on the hill to the west; this was the burial place of Brighton worthies like Martha Gunn, the most famous Brighton 'dipper', and Phoebe Hessell, who had disguised herself as a man to fight in the British army alongside her lover. St Peter's was designed by Sir Charles Barry, later the architect of the Houses of Parliament.

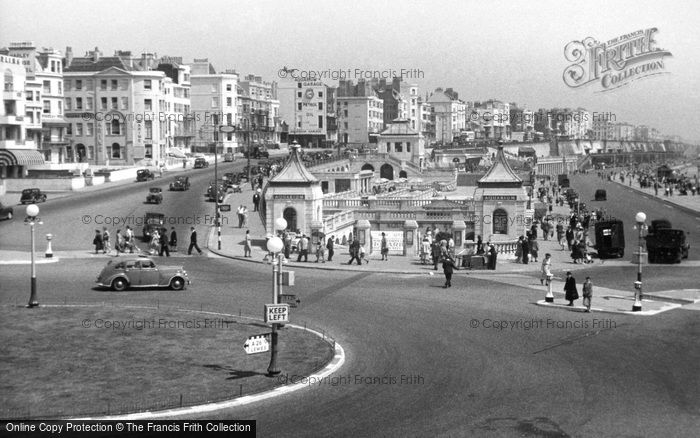

Busy, breezy 'Doctor Brighton', where the crowds came to take the waters and be dipped in the sea, is epitomised by the pictures in The Francis Frith Collection of the seafront from the Palace Pier westwards to Hove. King's Road, the seafront road of west Brighton, is named after George IV, who opened it in 1822. It was part of the principal 'carriage drive' of the town, and as such was not surfaced with tarmac until 1910. It was widened in the 1850s and 60s, and again in the 1880s, when the King's Road Arches were constructed beneath it and the birdcage bandstand built.

There is notable architecture in West Brighton, although the 20th century has punctuated and interrupted the majestic sweep of Regency and Victorian buildings. Big hotels like The Grand, The Norfolk and The Metropole still face seaward, but modern developments have replaced the old Bedford and the famous Mutton's, which closed in 1929. Regency developments like Brunswick Terrace (Hove) and Regency Square lend their elegance to West Brighton.

The Lower Esplanade from Palace Pier westwards to the lawns of Hove has always been the 'honky tonk' part of Brighton's seafront, the haunt of stalls and entertainers and later of private beach chalets, cafes and amusement arcades. The Western Lawns beyond the bandstand were laid out in the 1880s; they were improved in 1925 with the addition of a boating pool and putting green, and again for the Festival of Britain in 1953.

Beach donkeys were a feature of the Brighton seafront until the Second World War. They plied the lower esplanade with their youthful mounts, since the pebbly beach made it impossible for them to be ridden there. Dark rumours hung around these donkeys in the mid 19th century, for they were reputed to be used clandestinely by the local smuggling fraternity to carry contraband spirits. Goat carts were available for children to hire from the 1830s - they were expensive, costing one shilling per hour by the mid 19th century. The beach was always busy, and beach entertainers, including 'minstrels' with blackened faces, were very popular, though frequently of dubious merit. From 1891, pierrots in their black and white costumes were introduced from France. During the 19th and early 20th centuries there was a great vogue for boat trips from the beach; many former fishing vessels were thus employed, notably the 'Skylark', a boat that became so famous that 'Skylark' became a generic term for the pleasure boats of Brighton.

A walk to the end of the pier has been an essential ingredient in a Brighton holiday since the Chain Pier opened in 1823. The pier was designed as a landing stage for the cross-channel trade (Brighton to Dieppe was on the quickest route between London and Paris), but it was immediately popular with 'promenaders', who paid 2d, or one guinea annually, to walk the 13 ft wide, 1,154 ft long wooden deck. Brighton's Chain Pier was the first pleasure pier ever built, with kiosks contained in its towers and other attractions, including a camera obscura, at the shore end. The pier stood just to the east of the present Palace Pier, but today nothing remains. In its day it was a particularly fine structure, and both Constable and Turner were inspired to paint it. The entrance was via a new esplanade along the foot of the cliff, where the Aquarium (now the Sea Life Centre) now stands. The Chain Pier's popularity then took a tumble; in 1891, the Marine Palace and Pier Company was given permission to build a new pier (the Palace Pier), on condition that they demolished the Chain Pier. The company did not have to fulfil this condition - it was completely destroyed in a storm on 4 December 1896.

The West Pier, by the famous pier designer Eugenius Birch, opened in 1866, providing a fashionable promenade pier for the western side of Brighton. Initially there were few building on the pier, but in 1893 the pier head was widened and a large pavilion built. This was converted to a theatre in 1903 (it had its own repertory company during the 1930s) but in 1945 it was turned into an amusement arcade. A concert hall was added in the centre in 1916. Day trips to France from the West Pier were popular during the inter-war years.

The Palace Pier opened in 1899 and was straightaway a huge success. In 1901 it was embellished with a landing stage and an oriental-style pier head pavilion. The pavilion was remodelled as a theatre in 1910-11 at the same time as the bandstand (now the cafes) and the Winter Garden (now the Palace of Fun) were added. The theatre was demolished in 1974 after severe damage by a barge associated with the demolition of the landing stage. Pier head slot machines and funfair rides took its place. The Palace Pier has always been extremely popular, rising to its apex in 1939 when 2 million people visited it; 45,000 visited in just one bank holiday.

Since the early 19th century Brighton has been synonymous with fame and fashion, so perhaps it is only natural that nearby Hove prides itself on its gentility. Hove has developed from a number of hamlets to the west of Brighton. It has ancient roots, but it only started to grow in the 19th century when it began to fall into the gravitational pull of its big sister. The waters of St Anne's Well, a chalybeate spring, were recommended by Dr Russell in his treatise and brought visitors to Hove. Brunswick Terrace, perhaps the most magnificent Regency development in Britain, was completed in 1830, and further seafront terraces and squares followed. It says much that when you stand on the beach near the West Pier, the Hove seafront stands out as totally unspoilt, and little changed from the pictures in The Francis Frith Collection.

Beyond the seafront, Church Street is Hove's main commercial street. Up until 1966, it was dominated by the old Hove Town Hall. Although this has now gone, Church Street retains a discreet and gentle air. Hove has some particularly fine churches. The old parish church of St Andrew's nestles incongruously under the Victorian gasometer, and dates back to medieval times. All Saints, built at the end of the 19th century, is a superbly grand affair. St Leonard's, Aldrington, went up in the 1870s, and St John the Baptist's, which was built in 1852 to serve the Adelaide Crescent development, adds an elegance with a soaring spire of about 1870.

To the east of Brighton is Rottingdean, a coastal village sheltering in a little combe, and still largely untroubled by the presence of its noisy neighbour. If Hove is Brighton's genteel suburb, Rottingdean is Brighton's country cousin. Since the growth of Brighton, Rottingdean, with its 12th-century church built on Saxon foundations, and its tranquil village pond, has long been a magnet for artists and authors. During the Victorian era many were drawn to its peace and solitude, almost cheek by jowl with Brighton. The most famous were Rudyard Kipling and Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Their houses still stand.

Behind Brighton to the north rise the smooth, rolling South Downs. It was inevitable that Brighton's visitors would turn inland and discover their beauty. The magnet was the Devil's Dyke, one of the highest points on the Downs, which has magnificent views over the Weald. A branch railway put the Dyke on the map, and other strange conveyances - a hair-raising cable car across the Dyke and a funicular railway down the scarp slope of the Downs - added to its attractions. All have long since closed.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Brighton History in Photos

More Brighton PhotosMore Brighton history

What you are reading here about Brighton are excerpts from our book Brighton and Hove Photographic Memories by Helen Livingston, just one of our Photographic Memories books.