Bristol History

The history of Bristol and specially selected photographs

Once the second most important city in England after London, Bristol's early wealth was built on shipping with trade routes to France, Spain, and other European countries, though it would become famous for its involvement in the Guinea, or slave trade, between West Africa and the American colonies. In the late-18th century the city supported the American colonists in their pleas to Parliament and it was at Bristol that the first American Consulate in Europe was opened in 1792. The city also played an important role during the Civil War, and was later one of the towns, along with Nottingham and Derby, to be noted for its Reform Bill riots.

This famous old city situated seven miles up the Avon from the Bristol Channel was to rise to become the second most important city in England after London. As early as the 10th century there was a mint and in 1373 it was created a county in its own right. But it was the navigable Rivers Avon and Severn that gave Bristol the competitive edge; by the 12th century there was an established wine trade with the Bordeaux region which was soon extended to Spain.

In 1445 the Mariners' Guild was founded and there was a Fellowship of Merchants set up in 1500. In 1552 the Merchant Venturers were incorporated and from the on sea-going Bristol ships theoretically might be found anywhere in the known world though most were involved in the trade with Spain, though during the grain shortages of the 1580s several ships made trips to the Baltic.

During the Civil War the possession of Bristol was vital to the King's cause. While the Royal Standard flew over the second most important city in England after London, the diplomatic initiatives to obtain foreign military assistance had currency. If it fell then the King's cause would be seriously undermined. On 15 March 1643 Sir William Waller with a force of less than 2,000 Parliamentary troops had managed to secure the city, but the following July he was badly defeated at Roundway Down and his army all but destroyed. Prince Rupert marched on Bristol whose garrison had been stripped by Waller prior to his defeat, and summoned its defenders under Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes to surrender. Fiennes rejected the offer and two days later the Royalists attacked. Despite an outstanding defence which inflicted heavy casualties on the Royalists, Fiennes had little hope of holding out and had no alternative but to ask for terms. Magnanimous in victory, Rupert allowed the garrison to march out of the city with the full honours of war; drums beating and flags flying. Despite his stand Fiennes was tried the following August and condemned to death though he was later reprieved. Bristol now became the major Royalist base in the West Country for both land and naval operations, and a port for blockade runners bringing weapons and supplies from Europe. Mindful of Fiennes' experience in defending a city with a large perimeter, Prince Rupert set about strengthening the defences which included the construction of the Royal Fort on Windmill Hill.

Following Marston Moor, Rupert returned to Bristol in October 1644 to organise defences and prepare for an expected siege which came the following August after the Royalist disaster at Naseby. Ordering the burning of Clifton, Bedminster and Westbury, Rupert pulled his forces into the city. Though Rupert wrote to the King promising to hold Bristol, his own combat experience must have told him that it was a hopeless case. After putting up stiff resistance the parleying for terms began on 4 September 1645, the final surrender occurring on the 10th. With the loss of Bristol it could be argued that the war was lost.

Privateers and Slavers

During the 18th century a large number of Bristol vessels undertook voyages as privateers. Sailing under letters of marque, a privateer was a privately armed vessel authorised to wage war upon the king's enemies, in return for prize money. During

the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War the wet dock at Sea Mills was used as a privateer base. During the American War of Independence 157 Bristol ships sailed under letters of marque and during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars the city furnished a total of 63 privateers.

Not all the slaves handled by Bristol were from Africa. From the early years of the 17th century thousands of men and women were sentenced by English courts to servitude on the colonies of the New World, the majority destined to end up working on plantations. It was soon realised however that if the plantation system was to be maintained and expanded an alternative source of labour had to be found and by 1619 the first cargoes of negro slaves were being landed.

Until the Restoration, slaving was carried on by English, Dutch and a few colonial ships, but the majority of merchants involved in the Guinea trade as it was called were more interested in gold and ivory than human cargo. Things changed in the 1660s with the establishment of the joint-stock Royal African Company. From now on slaving would become the main traffic. The Royal African Company tried to maintain a monopoly on the slave trade, and though a few Bristol merchants held shares in it most were for free trade, and were of the opinion that any competent captain could cruise the West African coast, slaving at will. And this is precisely what most of them did. Despite a petition from the Royal African Company, Parliament threw the slave trade open to anyone prepared to pay 10 per cent tax on a voyage.

In 1707-08 of the 52 ships that cleared Bristol to take part in the Guinea trade, fifty were free traders. In 1725 Bristol cleared 63 ships with a total capacity for 16,950 slaves and though twenty years later the number of ships had been reduced to 47 the carrying capacity had dropped by only 310 slaves. Though Bristol and London controlled slaving they were soon to be eclipsed by a new player, Liverpool. With a different pay structure in operation Liverpool ships were more profitable per voyage than their rivals at London and Bristol. In 1753 Liverpool cleared 63 slavers, Bristol 27, London 13, Lancaster 7, Glasgow 4, Chester 1, and Plymouth 1. Between 1756 and 1786 a total of 588 slaving voyages were made from Bristol while Liverpool vessels made 1,858.

The slavers did not always have it their own way. In 1759 a slave ship operating along the Gambia River was attacked and boarded by natives. The captain who was badly wounded and seeing that his ship was about to be overrun, made his way to the powder magazine and fired his pistol into it. The ship blew up killing everyone aboard. In May 1750 the Bristol slaver King David was overrun by slaves who had managed to break into the arms locker. The captain and five crewmen were killed, the rest took refuge in the hold. The leader of the slaves, who spoke good English, told the surviving crewmen that if they came up on deck they would be spared, but as each man came topside he was put in irons and given Jonah's toss (thrown overboard). The mate was the last to come up, and was only spared when it was realised that there was no one else left who knew how to handle the ship or navigate.

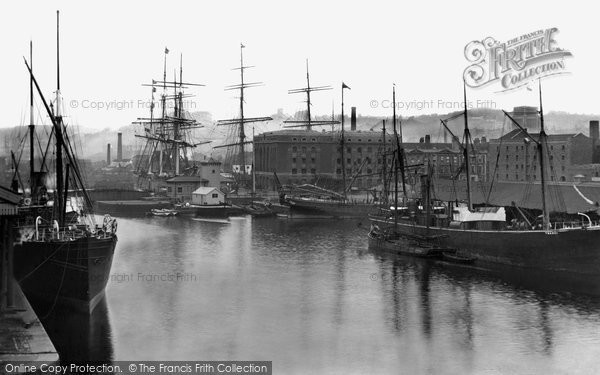

Bristol continued to send ships to West Africa that were unconnected with the slave trade but there were never many of them. In 1840 some of the ships clearing Bristol included 45 for the West Indies, 14 for Newfoundland, 14 for West Africa. 9 for Canada, 7 for Australia and 3 for the East Indies. In 1835 a cargo of tea was landed direct from Canton, but attempts to establish the Bristol Tea Co and offer an alternative port to London failed. By the early decades of the 19th century Bristol was suffering and loosing out to the likes of London, Liverpool and Hull due to the high charges imposed by the dock company. In 1840 Bristol had at least seven ships operating on the route to Australia, but dock dues, which were seven times greater than that charged by Liverpool killed the traffic. Exports to Australia remained but on a small scale.

It was only in the 20th century that Bristol, thanks to the development of Avonmouth managed to return to something like its bustling days of the 18th century. In 1890 it was selected as the UK port for the fortnightly Imperial West Indies mail service and from 1921 liners from Rangoon and Colombo were making scheduled calls at Avonmouth. An important boost for Avonmouth came in 1901 when Elders & Fyffes inaugurated their fortnightly service to Port Limon, Costa Rica. For over sixty years the banana ships would use Avonmouth and involve the railways in operating over 400 special banana trains a year.

Following the completion of the Royal Edward Dock in 1908, Avonmouth continued to expand. In 1911, twenty-seven oil storage tanks were installed near the docks and an oil basin was added in 1919. Between 1922-23 the eastern arm of the Royal Edward was built alongside which were constructed large transit sheds and granaries.

In 1938 the docks handled 51 ships carrying 231,000 tons of fruit, oilseeds, rice and tea etc from India, Burma, Ceylon and Malaya, while a further 86 ships discharged over 200,000 tons of cargo from Australia and New Zealand. The total for the year was 354 ships and over 1 million tons of cargo landed.

Matthew's Bristol Directory of 1828 states that 'Bristol is ranked the second city in England in respect of riches, trade and population.' Things were about to change. Industrialisation would see obscure places like Middlesborough which than had a population of less than fifty people expand in less than one hundred years to a town of over 90,000 inhabitants. In 1700 Bristol's population was approximately 20,000 which would put it in third place behind London and Norwich. By 1800 with a population of 60,000 it had slipped to sixth place and by 1850 with 137,000 inhabitants it would be ranked seventh. In terms of being a port, Bristol was in 1700 the second largest in England. By 1800 it had dropped to eighth but by 1855 had pulled back to sixth largest but ranked twelfth in terms of overseas trade.

By road and rail

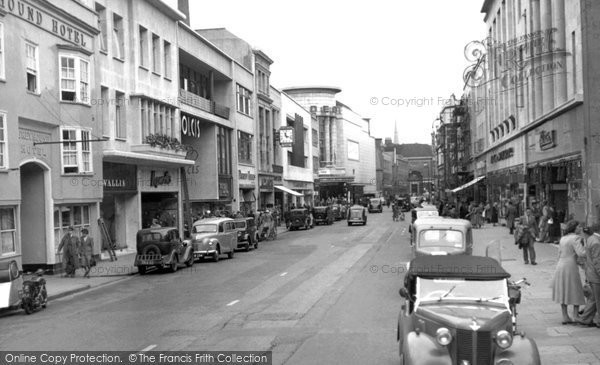

By the beginning of the 19th century the Bristol Mail from London offered a fast service, the 105 miles from Hyde Park Corner to York House on the outskirts of Bath being covered in just eleven hours. The coach was scheduled to arrive at York House at half-past seven in the morning, and after a change of horses proceeded through Bath and on to the Bristol road. At this time this section of road was considered to be the best in all England thanks to John Macadam. He had moved to Bristol around 1803 and later became surveyor to the Bristol Turnpike Trust.

On crossing the Bristol Bridge the coach continued up the High Street and then turned into Corn Street where the post office was situated, the scheduled arrival time being four minutes past nine. Bristol had one of the busiest provincial post offices in the country. There were daily Mails to London, Oxford, Birmingham and Portsmouth as well as a Welsh Mail and a West of England Mail. The office was also responsible for initial sorting of overseas mails to and from the Americas, Portugal and most Mediterranean ports. From the various inns in the city such as the White Hart and the Bush it has been estimated that over two hundred coaches arrived and departed daily. Bristol also had a considerable number of haulage firms operating scheduled services as far as Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire.

The railways came to Bristol in 1835 with the opening of the southern section of Bristol & Gloucester Railway which involved the construction of the 515 yds-long Staple Hill Tunnel. The Bristol terminus was at Avonside Wharf on the Floating Harbour. The second railway to enter the city was the Great Western, whose first train ran on the Bristol to Bath section on 31 August 1840. Ten trains operated on the first day carrying nearly 6,000 passengers and generating revenue the tune of œ476. The line to London was completed in June 1840. The third railway was the Bristol & Exeter, with twelve Bristolians on the sixteen-strong board of directors, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel appointed engineer. The line was worked with GWR locomotives and rolling stock, and when it opened throughout in May 1844, it was the longest main line in the country, the distance between London and Exeter being 194 miles.

Clifton Spa

As well as being a large prosperous city and port, Bristol, or more accurately Clifton, developed as a spa, the Hotwells proving popular with high society especially after the discovery of a second spring in 1702. During the 18th century Clifton became a fashionable resort and in this part of the country was second only to Bath. The resort had all the amenities one would expect; a pump room and assembly rooms were built in 1722: even branches of London shops would open there for the season. When Thomas Newton was Bishop of Bristol from 1761 to 1781, the Hotwells were popular with fashionable society, some of whom were Roman Catholic. England at that time Protestant in all things and those of the Catholic faith were in some situations legally proscribed against. On hearing that there was a plan to open a masshouse at the Hotwells, Bishop Newton called in Bristol's lone Catholic priest Father Scudamore for a friendly chat. Having taken government advice on the matter Bishop Newton left the priest in no doubt whatsoever that if he went ahead then the full weight of the law would be dropped upon him from a very great height.

In 1870 the Docks Committee ordered the demolition of most of the facilities, but even up to the outbreak of the Great War it was estimated that around 350 people a day went to take the waters. The well was finally closed due it being contaminated by river water which was seeping into it. A couple of bore holes were drilled, the aim being to strike the spring further back where it was hoped it would be pollution free, but they were unsuccessful.

In 1828 Isambard Kingdom Brunel was staying at Clifton for his health, spending much of his time on sketching expeditions along the Gorge. By coincidence in October 1829 the Merchant Venturers advertised for plans to bridge the Gorge, money having been left for the purpose by William Vick in 1752. Despite competition from experienced engineers such as Thomas Telford, one of young Isambard's sketches was selected. Brunel's original estimate had been œ52,966 but by the time the final design was ready the price had gone up to œ57,000. Vick's legacy would not be enough and it would be August 1836 before the foundation stone was laid.

Brunel's steamships Great Western and Great Britain were built at Bristol though both were too big to be able to use the Floating Harbour. The Great Western, which pioneered transatlantic steamer services, was a wooden paddle-steamer of 1340 tons, and though she was based at Kingroad near the mouth of the Avon, the money grabbing Bristol Dock Co still demanded full port dues on her. The Great Britain, being a much larger vessel and built of iron was immediately based at Liverpool where she was joined by the Great Western in 1842. Both ships drew large crowds when they were first towed out of Bristol and through the Gorge at Clifton.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Bristol History in Photos

More Bristol PhotosMore Bristol history

What you are reading here about Bristol are excerpts from our book Around Bristol Photographic Memories by Clive Hardy, just one of our Photographic Memories books.