Cheltenham History

The history of Cheltenham and specially selected photographs

Cheltenham adorns the borderland between the western escarpment of the Cotswolds and the broad plain of the Vale of Gloucester like some architectural jewel - a perfect Regency health spa, almost untouched at its heart by the unkind developments that ruined so many British towns during the 20th century.

Three centuries ago Cheltenham was a not very distinctive country community; "a market town in the vale" commented the Tudor topographer Leland when he called there during the reign of Henry VIII; a place visited mostly by shepherds with their flocks, wool packers, and later stagecoaches and sundry travellers on their journey to somewhere else. Cheltenham enjoyed little fame except as a town at the back of beyond.

Yet, people have lived on this site since Roman times. Saxon armies marched this way and Anglo-Saxon kings established a religious house, perhaps not grand enough to be called a monastery, in the immediate vicinity - a building probably burnt out of existence by Danish marauders who ravaged the fledgling community on the banks of the little River Chelt. In medieval times much of the surrounding land belonged to the church, local people earning a living from the wool trade and the growing of crops. It was around this time that the market that Leland visited was established. It is quite likely that the stone for the more substantial buildings of the town was taken from quarries in the neighbouring hills, just as the Georgian builders of the spa obtained it centuries later. But most of the everyday residences probably would have been made out of wood from forests that were still being hewn down and pushed back at the time. The population at around the time of Leland's visit would probably have been around a thousand.

The future spa town's first mineral spring was discovered in 1715 by a careful observer who had spent some time watching the watering habits of the local pigeons, who always seemed so fat and full of life. A pump room was constructed in 1738 and towards the end of the 18th century, King George III gave the growing town the royal seal of approval by bringing his family to take the waters. Business boomed and when the town of Cheltenham Spa became a city, its grateful citizens incorporated a pigeon into its crest.

Clearly, the old Cheltenham could not provide either the ambience or the practical facilities to cater for its new upmarket clientele, who were beginning to grumble about the quality of ancient inns and small boarding houses. So, a calculated campaign of redesign and rebuilding was inaugurated. The hillside quarries were plundered once more for their stone, and the subsequent building boom was to give us the beautiful and elegant Cheltenham that we know today, with its wide avenues, handsome terraced houses and luxury villas.

The old line of the town had followed the ancient route that is now High Street, but the great open spaces on either side were now incorporated into the settlement. Assembly rooms were opened so that balls and entertainments might be held to amuse the growing number of visitors, after they had spent the day taking their water treatment. Walks and formal rides were laid out for beneficial exercise and roads eventually paved to allow long-gowned ladies to avoid the usual mud of the thoroughfares.

Cheltenham came into its own upon receiving the patronage of the royal family. The long drawn out Napoleonic Wars, which closed off the Continent to wealthy visitors, brought a great influx of visitors to the spa. Several new mineral springs were opened; many with elaborate pump rooms designed to cater for the most fastidious of tastes. In the aftermath of the war, the town began to spread across what had been green fields and open common land as its citizens attempted to absorb this increased number of patrons. Cheltenham's population grew substantially at this time as many visitors, who had fallen for its charms, decided to settle.

The 19th century saw the town expand as retired empire builders, colonial civil servants and pensioned military officers sought refuge after a lifetime in warmer climes. Not everyone was impressed. The social commentator William Cobbett in his book 'Rural Rides' considered Cheltenham to be a "nasty ill-looking place", full of "East India plunderers, West Indian floggers, English tax-gorgers, gluttons, drunkards and debauchers of all descriptions, female as well as male." Cobbett hurried on to critically examine other places. His judgement may seem harsh, but all fashionable resorts at that time probably attracted an equal measure of exploiters and hanger-on, given the rich pickings that were to be had.

Evidence suggests that Victorian Cheltenham was a calmer place. New streets were laid out, houses built and churches founded. The importance of the town began to depend as much on the fortunes of its residents as visitors. This was particularly the case with the development of Cheltenham as a renowned seat of learning. The first colleges, founded early in the Queen's reign, were private concerns, effectively companies, with the shareholders entitled to nominate pupils. Many of the original boys were the sons of army officers and their education was designed to equip them for a future career in the services. By the middle of the 19th century, the colleges had acquired considerable reputations throughout the British Empire, so much so that families in far-flung corners of the Empire were starting to send their children across the waters to gain a Cheltenham education.

Cheltenham Ladies College came into existence to cater for the daughters of the newly affluent middle-class, who to a certain extent were being communally educated for the first time. Headmistresses such as the pioneering Miss Dorothea Beale took up the challenge, providing a real and substantial education, very different from the simpler acquirements of the earlier girls boarding academies or the skills passed on by governess' and private tutors. Miss Beale believed that girls should be able to compete with boys, at least academically. She saw her college as a preparation for a university education and added to Cheltenham's groundbreaking reputation as a centre for the proper education of women. A number of her pupils went on to achieve entry to the women's' colleges that were opening at Oxford and Cambridge.

The presence of these educational establishments gave Cheltenham the atmosphere of a university town, though there has always been a local debate as to whether or not the architectural merits of the college buildings match that of the standard of education.

In the last century, Cheltenham became a busy city with its modern industries, world-famous music and literature festivals, and National Hunt Racecourse - home of the Cheltenham Gold Cup. Despite the reduction of the city's importance as a spa, Cheltenham has continued to attract tourists who find the place an admirable touring centre for the Cotswolds and Vale of Gloucester. Much of the Georgian and Regency heart of the old town has remained intact; for developments and industries have tended to ring the town rather than invade its old centre.

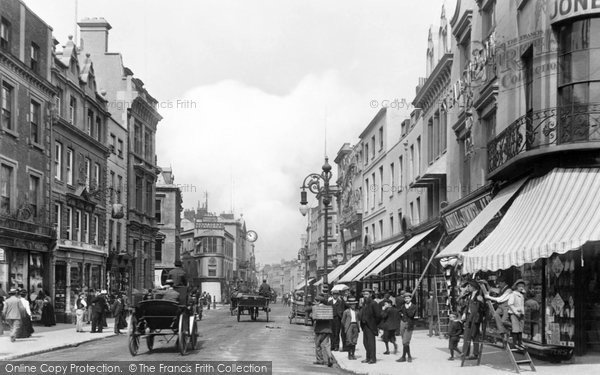

The Frith photographers captured these scenes of Cheltenham at a perfect time, before its streets became too cluttered with the intrusive presence of the motor car, and with the old spa town relatively intact and not so very different in appearance from the health resort so loved by earlier generations of visitors.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Cheltenham History in Photos

More Cheltenham PhotosMore Cheltenham history

What you are reading here about Cheltenham are excerpts from our book Cheltenham Photographic Memories by John Bainbridge, just one of our Photographic Memories books.