Then I Bought A Boat.

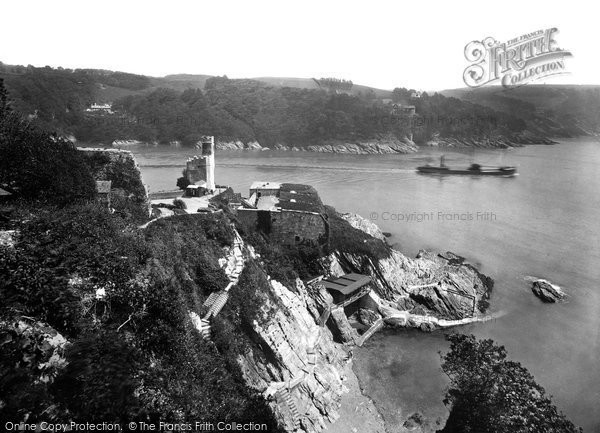

A Memory of Dartmouth.

For some time I had been thinking it would be nice to own a boat, and with this in mind I would keep my eyes open. It was only then I discovered boats for sale were very few and far between. You might think in a place like Dartmouth there would be plenty of boats for sale, but as post-war private boat building had yet to get into full swing, there now appeared to be a shortage of second hand boats for sale.

Imagine my excitement when my friend Mike told me he knew where there might be a boat for sale. His friend, Mike Barratt (MB) owned a boat and was thinking of selling it. M.B lived in Dartmouth and went to the same boarding school in Exeter as my friend Mike. I questioned Mike, what type of a boat was it? Where was it kept? Did it have an engine? How much did he want for it? Mike replied the boat was an eleven foot clinker built dinghy with an outboard motor and was kept in the boat-float at Dartmouth. The asking price was £35.00.

Mike’s description of the boat sounded it was just the sort of boat I was looking for. I talked it over with my dad he said it sounded alright. I had saved my paper delivery money so there seemed no reason why I shouldn’t go ahead and have a look at it. We all met at the boat float (small boat harbour) in Dartmouth where Mike introduced us to his friend M.B. With introductions quickly over, M.B pointed out the boat where it was gently floating in about three feet of water. I was pleasantly surprised; it was just what I had in mind. The boat looked sleek and graceful, its varnished coat setting it off nicely. It was secured both ends with a bow-line tied to an iron ring in the harbour wall and at the stern a disappearing line to the mud below. The boat looked a treat, just what I was looking for, I asked M.B where the outboard motor was, and he replied it was at his house, which was at the top of Dartmouth. The motor was an ancient ‘Seagull’ and was precariously clamped to the side of a nearly over full water tub, the idea being to start the motor and prove to everyone’s satisfaction that it worked. I must confess I had my doubts about embarking on such action as it all looked a bit Heath Robinson to me. M.B began to explain. To start the engine a strong cord with a handle is automatically spring loaded around the flywheel, all that is needed to get it going is a short sharp tug. To my amazement, after two or three tugs, the engine roared into life, immediately soaking everyone present. Hilarious laughter burst out as each of us shook off water like a dog. With everyone satisfied, it was hand-shakes all round, it was a deal, and the boat and engine was mine.

I was still living in Dartmouth at the time but later we we were to live in Kingswear; I hadn't given much thought as to where I would keep the boat but I think I had already made my mind up to keep the boat in the creek in Kingswear, after all, this where I spent most of my time. The creek was an ideal place to start, until I could come up with something more permanent in the river itself.

Looking back, I’m surprised how naive I was about how things should be done, for I assumed it would be ok for me to keep my boat in the creek just because everybody else did, it never occurred to me someone owned the land and permission would have to be sought and possibly a fee paid. I had no idea there was such a thing as harbour fees or mooring rights - such was the blessed ignorance of youth. In no time at all the boat was settled in its new home on a grassy bank by the railway sidings, the motor was kept in the shed at home, and whenever needed, was carried on my shoulder down to the river.

I hadn’t had the boat long when a former neighbour from the Midlands came down to call on us as he was on holiday in the area. His name was Pete and was a few years older than me and a wizard with things mechanical. I took him on a trip in my boat on the river and gave him a go at the controls. Pete asked me if the engine had a reverse gear, I said it had but it didn’t work. He said he would have a look at it when we got back.

Back home, he stripped down the gear mechanism and in no time at all pointed out the problem. The metal on the gear shift had been worn by the prop shaft and was not locating in reverse gear. He thought it could be remedied fairly easily, I hoped he was right as it would be very useful to have a reverse gear.

We took it to the local garage but they said they couldn’t help, I thought of the blacksmith down by the cinema and we tried there. Adjusting our eyes to the gloom, we found ourselves back in time, for this place was like a scene from history. We explained to a pleasant burly man in shirtsleeves, wearing a heavy leather apron tied in the middle with string, he seemed confident he could fix it. I watched with keen interest as he went to work using tools positively ancient. We could not but admire his skill as he fashioned and braised new metal to old; soon declaring it was the best he could do. We thanked him and went our way. Sadly, when we tried out the motor the metal soon wore away again, it was simply not hard enough to withstand the grinding of the propeller shaft against it. I continued to use the motor without the reverse gear for the remainder of the time I had it. I did not even miss it. As for the blacksmith’s shop down by the cinema, I thought it had long since gone, but I learned a few years ago it was still there. As I write, I suspect they both might now be gone.

Mr Penwarden was the chief goods clerk at the local railway station at Kingswear where I had just started work. We immediately became firm friends which is strange really as he was old enough to be my father and then some. I already knew he had a motor boat which he kept in the creek, and he in turn knew that I had recently acquired a boat of my own. Pen (as he was universally known) had been a boat owner for many years and during our conversations he gave me lots of tips and advice, in fact the help he gave me with my boat was invaluable. It was late in the year and I planned to soon lay up the boat for the winter in preparation for the following spring.

In the time honoured manner, the boat was heaved out of the water, turned on its back and chocked up with timbers. With scrapers and sandpaper, lead paint and varnish I set to work. Surprisingly, within a short time I began to get the hang of things, considering I had had no experience in such matters I was becoming confident and part of the local boat scene. Seeking advice here and there, sometimes just talking and discussing, I quickly picked up the jargon and the way things should be done. Ideally, the boat need sealing with caulk string but really didn’t feel I knew how to do it so I compromised and coated the bottom with a thick coating of bitumen supplied courtesy of the packers. (Permanent Way gang)

Everything else looked straight forward, just keep scraping and scraping until all traces of old varnished was removed, both inside and out. When this was done, sand down sufficiently smooth to start painting and applying varnish. Easier said than done, it was well into the new-year before I could give it a final coat of varnish. Winter gave way to spring and my boat was ready, well almost, there was one final thing to do. I had long decided what the boat’s name would be, I had decided to name it ‘Sea Fever’ from Masefield’s poem, which we did at school. To finish the job off I wanted to paint the name on the stern seat board. I gave much thought to the design and took care over the choice of colours to be used. I was well satisfied with end result.

Things had gone well, my boat, now resplendent, bobbing in the water waiting to be taken out.

The creek was certainly a good place to keep a boat but there was however one drawback, it was tidal! This meant you could only take the boat out and back according to the state of the tide. You can imagine the inconvenience this caused. The only thing to do was try and find a mooring on the river where you could come and go as you pleased, but this in itself caused a further problem where new moorings would have to be set up. Though the river was still tidal, this could be overcome by using a running mooring which enabled you to access your boat at any state of the tide. I consulted my friend and work colleague Mr Penwarden, and as if my magic he obtained permission for me to moor my boat off the footbridge across the railway lines. Underneath the bridge was a small brick built shelter, which was just handy to store my outboard motor. Pen also acquired all necessary mooring equipment, such as pulleys, hundreds feet of rope and an anchor weight. But above all, he gave me access to his great fund of knowledge. It was surprising how quickly I became skilled at preparing and handling the boat, either by rowing or with motor, I enjoyed doing both. If I planned not to go far I would row, but if I was going any distance then I would use the outboard motor.

One summer’s evening I was messing about in the creek, the tide was fully in and the translucent green water dead calm. I was fascinatedly peering into the transparent water. All alone, I started to slowly row and was surprised how deceptively quickly the boat was slicing through the water, I kept increasing my speed till I was going really fast - regatta style, I was heading for under the bridge and into the river.

Way up above on the steeply wooded slopes of the creek I could hear gin clear voices from someone’s garden. I decided to give them an exhibition of rowing and put my head down, paddling pell-mell. So engrossed was I had forgotten to check my course for the bridge and the next thing I knew there was an almighty crash as I smashed into the railway embankment wall. I was catapulted forward in a heap, the oars flew out of the boat and into the air, splashing down into the water skimming away in different directions.

I had hit the railway bridge wall! Badly shaken I gathered my senses in time to see if the people up above had seen what had happened, they had! They were still there looking down. I had never felt so embarrassed in my life; it served me right for showing off. Surprisingly the boat was not damaged and neither was I, except for my bruised ego.

This was the coronation year 1953. The new royal yacht Britannia sailed into Dartmouth, with its equally new queen, and moored in the middle of the river. One evening, my Dad, me and the dog went out to have a closer look, we found ourselves among a few other assorted craft doing the same thing. We got quite close, what a beautiful ship, it was gleaming as we could see the reflection of our boat as we passed by. As we circled, we could see the ships barge come alongside to take someone important ashore. With smartly dressed sailors piping their passenger aboard it was an impressive site. That someone was Prince Philip on his way to the Royal Yacht Club. As the Royal Yacht’s barge majestically passed close by my Dad waved to him, Philip ignored him. My dad was miffed and never thought much of him after that.

A day out on nearby Lighthouse Beach found us fishing with my boat. With me were my elder brother and John Memory. I was fishing from the shore while my brother and John were out in the boat, they would come in to the beach when I signalled that I wanted my bait taken out to a given spot. The boat came in stern about and I carefully handed John the baited treble hook, I gave the all clear and the boat pulled away with me releasing the line from the reel. As the line was gradually taken out, I shouted and signalled to John to drop the bait into the water, there was no response. I shouted again and a panic ridden voice came back that the hook was stuck in his hand and he couldn’t let go! The momentum of the boat continued forward and soon all the line was spent - what was I to do? There was only one thing, I started to wade out as quickly as I could and then threw the rod into the water where it continued and sank. My imagination was working overtime, what were John’s injuries? How badly was his hand torn? Truth to tell I cannot remember, I do not even remember if he went to hospital, alas, I cannot ask John himself what happened as he is no longer with us, for I have heard John passed away some time ago.

Another visitor came to stay with us, this time it was a friend from my old school. His name was Bob, and we shared the same interests. We were eager to explore the area for sea birds eggs. I had decided to take him to a place where I knew there was a colony of rare seabirds. With the boat loaded with rope we set off. After an uneventful journey of about an hour we found ourselves landing on Scabbercombe beach. Scabbercombe is a small secluded bay hemmed in by high cliffs. It was on these cliffs the seabirds nested. We dragged the boat up the beach to safety and unloaded our piles of rope.

Each laden with huge coils of rope, we must have looked like Himalayan Sherpas as we staggered up the steep grassy slopes to the top.

It was a really hot day with unbroken sunshine and soon we were sweltering, we needed several breaks to gain our breath on our way to the top. Finally we made it, collapsing in a heap of rope, exhausted! The idea was somehow to secure the rope at the top and throw the rope down the cliff-face to where the eggs were.

Looking around, we could see it was not going to be as easy as we thought. From down on the beach the cliffs looked almost sheer, but this view was deceptive and not the case. At the top, large areas sloping down to the cliff edge were waist deep in fern and brambles making it hard going carrying the heavy rope, it was almost impossible to tell where the edge of the cliff actually began. We tied one end of the rope to a trunk of a tree and tried to throw the rope down.

This was far more difficult than it sounds, the heat of the sun making every move tiring. We finally managed to heave the heavy bundle of rope over the edge in the hope it would reach the rocks below. It took a great deal of manoeuvring to try and align the rope to where the eggs were below, but it was hopeless, the only way was for me to go down to the beach and boat and row out to where the rope was dangling. Soon I was rowing the boat out to where I could see the dangling rope. As I rowed I could see Bob a distant figure at the top. Nearing the rocks I could see the rope’s end dangling invitingly. I managed to grab hold of the rope and tie it to the stern of the boat, I then rowed away from the rocks and the rope tightened. I signalled to Bob to do his bit and between us managed to place the rope exactly where we wanted. I signalled Bob to come down and join me, by which time it was past midday. Between us we examined the next move and soon found another problem, the eggs were on a ledge about 30 feet up under a huge overhang not unlike a cave entrance. The rope hung vertically from the top of the overhang which meant one of us would have to shin up the rope to reach the eggs. During all of this my boat was bobbing about in fairly deep water nearby.

I managed to get Bob to volunteer to shin up the rope whilst I held the bottom taught so he could climb more easily, well that was the theory anyway. Bob set off and did very well to get level with the ledge the eggs were on, trouble was, no matter how he tried he could not reach them, for the eggs were inches away from his fingertips. He held on trying as long as he could but had to come down, he was simply drained. So near yet so far, surely we hadn’t come all this way only to go home empty handed. Then I had an idea!

What we needed was something on a stick to scoop the eggs off the ledge without breaking them. I knew just the thing, a child’s fishing net. My dad had a dozen or more in his shop.

There was no alternative but to walk back to Kingswear by road to get the fishing net which I knew my Dad had in his shop, it was a gruelling six mile round trip in the heat of the midday sun and by the time we got back to the beach it was mid-afternoon. We found everything just as we had left it, the rhythmic pounding of the surf of thousand years each wave progressing further up the beach.. Apart from our village trip we had not seen another soul all day, it seemed we had been here for hours and so we had.

Now armed with a child’s fishing net we headed for the rope’s end, still gently swaying in the now onshore breeze. Bob wasted no time in climbing the rope to the ledge, this time there was no problem, everything worked just as I thought it would and not a single egg was lost. With our task completed, Bob decided to take a further look round as he’d spotted some guillemots further up the cliff, where the cliff face was sheer and crumbly. Meanwhile down below, I was in my boat, holding steady in fairly deep water, watching Bob way above me edging limpet-like across the face of the cliff. His feet were inching along, arms outstretched, hands gripping flimsy rocks, dislodging showers of fragmenting rocks splashing down around my bobbing boat. I became fearful that he would fall. I remember shouting up to him that if he lost his footing he should try and kick himself away from the cliff face and attempt to find deep water where I would pick him up. Luckily he did not have to.

It was time to go home.

We loaded the boat and pushed it into the surf and scrambled aboard, it was Bob’s task to man the oars and try and keep the boat head on to the incoming surf whilst I tried to get the motor started, it was not an easy task as the boat was being buffeted by a lively incoming breeze and butting surf, I was trying to balance myself while attempting to get the engine started, all the time the boat being flung back by the waves and strong wind. Bob was not finding it easy to make headway and gain sufficient depth to start rowing. Something told me things weren’t right, something had changed since the morning, it must be the tide or the wind or both, conditions had certainly changed and making things difficult. We had been so busy during the day we hadn’t noticed, but now it was only too obvious. The boat was bucking like a bronco and Bob was struggling, a large wave hit us and the boat lurched wildly as an oar skidded into the surf, I grabbed the other oar and splashed after it, I lunged out and somehow managed to pluck the oar from the water. It was obvious I had to get the engine going quickly.

Trying to keep my balance I wrenched the pulley to start the engine, to my horror flames started to lick from around the fuel tank.

I could see immediately the fuel cap had come off, and a spark from the plug had ignited the fumes, the tank could blow at any moment. In desperation I frantically picked up the first thing I could lay my hands on which was a cloth used for mopping up any water in the boat, luckily the cloth was soaking wet with all the water we had taken on board, I quickly threw the soaking cloth over the fuel tank and the flames died and went out. I quickly screwed the fuel cap (which was attached to the neck of the tank by a short chain.) tightly back on and thoroughly wiped the engine dry. Dare I pull the cord again? With no time to think I whipped the cord and the engine kicked into life, I feared flames would instantly appear but there were none.

I opened the throttle and the boat butted its way into deeper water, we had made it - we were on our way.

A flawless blue sky, cotton wool clouds, the steady droning of the outboard made us feel drowsy and content. What a day!

I pointed the boat homeward. Keeping parallel to the coastline on the starboard side the cliffs would guide us into the river and home. It was a spectacular summer’s day, an azure sky hosting floating cotton wool clouds, the sun’s heat tempering fine spray from the boat’s bow forward. With the boats engine beating a steady rhythm, we relaxed and settled down, Bob lying flat on his back, spreading across the seats face to sun. We were about a quarter of a mile from the shore, myself sat steering on the stern seat. I played back the day’s events as I followed the contours and the beauty of the coastline. We ran parallel to the coast between the Mewstone on our left and Brownstone Battery on the right. My eyes roamed to the pine clad cliffs with its vivid greens and backdrop blue, truly a scene of rare beauty.

As we ran between the shore and the Mewstone I noticed the topography of this seascape forms a tidal phenomenon whereby the placid water rose and dropped by some 10 feet or more. Such conditions are called a ‘swell.’ I was jolted horrified when I witnessed a huge hole appear a few feet away revealing jagged rocks not far from where we were. Had we been over that portion of the sea we would have dropped like a stone and been smashed to pieces. The sea rose up quickly and covered the rocks as suddenly as it had dropped.

Bob had been oblivious of the gaping hole. We motored on between the castles, we would soon be home.

Addendum.

This was the first time I had been out to sea in my boat albeit keeping close in to the shore line. As a rule, I usually kept to the confines of the river. I have to pinch myself to realise how naïve I was, for anything could have happened, there wasn’t even a lifebelt on board. I had no idea what was under the boat at sea. On our return from Scabbercombe there was a moderate swell off the Mewstone when something caught my eye in the water, the boat was gently rising and falling several feet with the swell, as the boat rose up with swell a massive trough formed nearby to the boat revealing a huge mass of barnacle encrusted rock with wicked jagged edges, that would have ripped into my boat had I been nearer. What had caught my eye was the tip of the rock causing a mere ripple on the surface. I cannot recall whether Bob noticed this near miss or not – he never mentioned it.

There was a similar occasion when I went fishing one evening on my own; I was anchored up between the castles just of the Kingswear side. It was a calm evening with little boat traffic and I was quietly fishing when I heard a commotion coming from a few away to my left. I couldn’t make out what I was seeing and then it disappeared, only to reappear a little further away, I was given a repeat performance for a huge whale like tale rose into the air and crashed down onto the surface of the water, this action was repeated several times in quick succession before disappearing again. By this time I had reeled in my line, threw down my rod, hauled up the anchor, and started the outboard all in quick succession. I have never moved so quick in my life. I opened the throttle and sped off not looking behind me.

Back on land, I told and retold my story to anyone who’d listen, only to be met by a puzzled look and furrowed brow, all whilst backing away from me. What’s the matter with these people, why didn’t they believe me? Was it me? Then another chap heard me down on the jetty, he nodded sagely, ah! Yes; that would be a thresher shark he said, they feed on mackerel this time of the year, they get among the shoal and stun them with their tale, and then Hoover them up. Thank you that man, I was beginning to have my doubts.

Coming from a Midland industrial town, I had started out completely ignorant of things nautical, neither water nor boats, I had come a long way since then.

Note.

It wasn’t long before I had to leave Kingswear to serve my National Service, (June 1956) this would mean I would not be able to look after my boat and would have to sell it. I had messed about in my boat for three years and it had given me enormous pleasure. You would think it would have been a sad loss for me when it came time to part with it.

Strangely, I cannot recall any of it; I don’t even remember who I sold it to or what became of it. My Dad could tell me if he was still with us, but he’s not, and now I shall never know. Funny that!

I have often wondered what my boat’s history was. The outboard motor was old and of simple design but of excellent build and endurance. The boat, as already described was a clinker built and 11 feet in length. Sleek in looks with a varnish finish, it was a classic of its day. How old was it? I do not know, same can be asked of the Seagull outboard. The Kingswear and Dartmouth of those days were very redolent of the 1930's, my time there was a one off time warp, a missed decade of the war years gave me a once in a lifetime adventure. The 50's and 60's were ahead.

Thanks to the wonders of Google I learn that Seagull manufacture began in 1931 and are astonishingly, still being made. I would like to think both boat and outboard were of 1930’s vintage, for that is the era they invoked in me.

End.

IG.

Add your comment

You must be signed-in to your Frith account to post a comment.

Add to Album

You must be signed in to save to an album

Sign inSparked a Memory for you?

If this has sparked a memory, why not share it here?

Comments & Feedback

Be the first to comment on this Memory! Starting a conversation is a great way to share, and get involved! Why not give some feedback on this Memory, add your own recollections, or ask questions below.