Exeter History

The history of Exeter and specially selected photographs

You can arrive in Devon by plane, train or car. Travelling along the A30 trunk road, you will be following a course similar to that chosen by the Romans two thousand years earlier. You can come along the A38 from the Midlands or use the modern M5 which actually bypasses the city. Motorways are undoubtedly fast and convenient for the long-distance traveller; but what they do not do is allow you to discover this lesser-known treasure of England, the ancient city of Exeter.

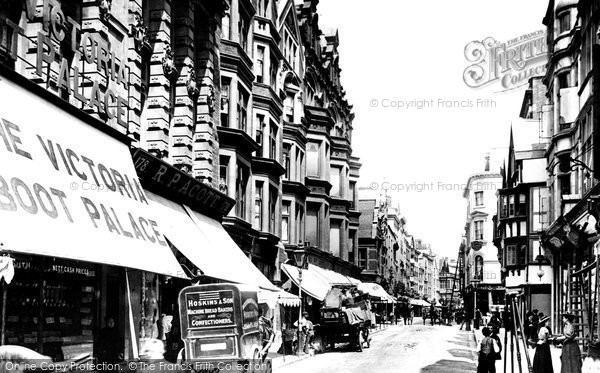

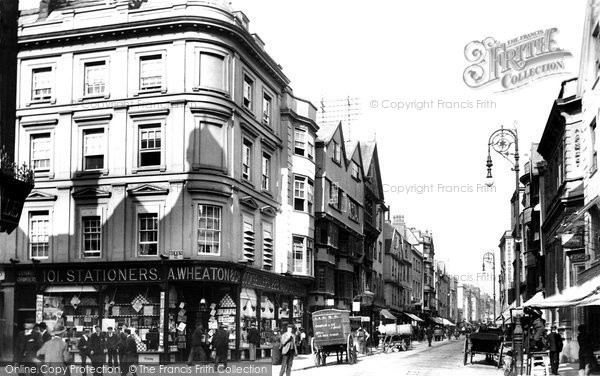

The Romans established their most westerly fortress here in 55Ad when Isca Dumnoniorum was chosen as a base for the 2nd Augustan Legion. The formidable barrier of Dartmoor must have been something of a deterrent to detailed exploration beyond, although there are many examples of Roman development further west. Later, a walled town was built here, and there are many remains of those Roman days still to be seen within the city. Even the main thoroughfare - High Street - is believed to be based on the old Roman road.

After the legions were forced to leave Britain, there is a hiatus in our knowledge of the Exeter area, lasting nearly two hundred years. Then, in the 7th century, there are records of a monastery; by the 9th century, Alfred the Great was fighting the Danes out of Devon, and is believed to have spent time here.

As is the case in so many of our great cities, it was the establishment of religious settlements that became the catalyst for real development. Before the Normans arrived, Exeter had become a see with its own bishop. For well over a century, the see in this corner of Devon had been in Credition. It was Bishop Leofric in 1050 who obtained papal permission to move his see behind the walls of Exeter. The magnificent cathedral was built a century later, and subsequently various priories and friaries were established.

Exeter had a mayor by 1205; it was second only to Winchester in provincial cities, and the establishment of a port had much to do with the wealth created hereabouts. But a combination of a silting river and a weir constructed by a local noblewoman saw trade move downriver towards Topsham. It was not until the opening of the canal in 1566 that it was possible to trade directly into the city again.

Because of its proximity to good sheep country, wool has always played a major part in the economy of Exeter. The Worshipful Company of Weavers, Fullers and Shearmen of the City of Exeter ruled the roost for many a long year; Tuckers Hall still exists on Fore Street.

But this part of Devon had also displayed something of a stubborn streak over the centuries. The city resisted the advances of William the Conqueror in 1068 and was under siege for eighteen days before it fell. Rougemont Castle, on the highest point in town, was constructed as a result of that fracas. The city was attacked again in 1497 when the Flemish pretender to the throne, Perkin Warbeck, tried to enter with his small army. He failed at that time, but soon succeeded in making an entry - in chains. Henry VII held him here before removing him to the Tower of London and a date with the executioner.

After the Henry VIII's Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries of the mid 16th century, a large portion of the populace rejected the new religious changes, wanting to stay with Rome. This occasioned more bloodletting. But it was nothing to the gore that flowed after the Monmouth uprising of the late 17th century. It was during the reign of James II that the Duke of Monmouth rebelled and was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor in Somerset in 1685. Some of the rebels were brought to Exeter, where the infamous Judge Jeffries held one of his Bloody Assizes: 80 rebels were hanged here.

Peace and prosperity then reigned until a frightening event took place in the spring of 1942 during the Second World War. On the explicit instructions of Adolf Hitler, several of England's more attractive cities were targeted for what he called 'reprisals'. He claimed that the British bombing of the port of Lubeck had caused many casualties, and that therefore the German's terrorising of the civilian population was justified. On three successive nights at the end of April and again in May, bombs rained down on Exeter. 1,700 buildings, including some of the finest Regency houses in the city, were destroyed in these raids. A further 14,000 were damaged, and civilian casualties were heavy. The cathedral suffered from the effects of a 500lb bomb which demolished three bays of the south choir aisle. Luckily, much of the precious ancient glass and portable objects had previously been moved to a place of safety; the cathedral would be rebuilt and the valuables eventually returned.

With the coming of peace, rebuilding the centre of Exeter became a priority. It is sad that lack of flair and unsuitable building materials have created several areas of utter boredom. Gone are the flowing Regency lines, which are replaced by bland red-brick and dirt-streaked concrete. But overall the city is still a place of compelling attraction. Because the old centre is so compact, a walking tour of the whole place is easy to undertake.

Beyond the town centre, the river is a focus of attention, followed by the canal. This was the first artificial navigation with locks in this country. It brought a degree of wealth and prosperity to the city, and created its own little world around the canal basin. Much of this can still be seen today. The Customs House was the first brick house in Exeter, and is now preserved. Several of the surrounding buildings create an authentic atmosphere much admired by both film and television producers looking for locations for their period pieces. One of the most famous - the television series 'The Onedin Line' - was filmed here. It is sad to report that activity on the canal is now minimal. The Museum has dispersed, and the only commercial trade - a ship carrying sewage slurry out to sea for dumping - ended at the end of the last century.

The other major transport revolution was, of course, the arrival of the railways. This part of the country was the domain of that greatest of early railway engineers, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The Bristol and Exeter Railway opened in the spring of 1844, and the continuation towards Torquay and Plymouth was opened in 1849. Exeter would become a rail cross-roads with branch lines to both north and south; with the arrival of the London and South Western Railway in 1860, expansion would continue as this company moved into northern Devon and Cornwall. In later years, these lines would become known as 'the withered arm' of the Southern Railway.

Topographically, the Exeter area is dominated by the valley of the River Exe. Indeed, it was at the lowest crossing point of the river that the Romans built their fortress. It is surprising to discover that the Exe rises way up in the north of Devon, only a few miles from the Bristol Channel. The Yeo and Culm join the Exe just north of Exeter.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Exeter History in Photos

More Exeter PhotosMore Exeter history

What you are reading here about Exeter are excerpts from our book Exeter Photographic Memories by Dennis Needham, just one of our Photographic Memories books.