Grimsby History

The history of Grimsby and specially selected photographs

Grimsby, or more correctly Great Grimsby, situated on the east coast of the nation's agricultural heartland of Lincolnshire, is a fascinating town. At one time the largest fishing port in the country, the town and its nearby settlements add a vital and exciting chapter to the cultural heritage of the country.

But where did it all start?

In pre-Roman times, the Lincolnshire Wolds and its surrounding environs were home to the Celtic tribe of the Coritani. The capital of their civilisation, though based in Ratae Coritanorum (Leicester), extended over the Lincolnshire Wolds and right out to the coastal areas that encompassed the regions now covered by Grimsby and the south bank of the Humber estuary.

The Romans began their conquest of Britain in the mid first century AD. They established a military fortress at Lindum (now Lincoln) on the Wolds, and set up posting stations at nearby Owmby and Caistor. In these times, the area surrounding Grimsby was a source of salt (which was got by panning), and this was a reason for the Romans to extend their dominion into the area as far north as Caistor, some 12 miles south of Grimsby. Coming northwards from here, around AD 100 a small group of Roman workers appears to have settled at an unnamed site on the Humber bank - this in time formed the nucleus of Grimsby today.

However, it was the advent of the Danes that first saw the founding of the town upon which its history is founded. These seafaring aggressors appeared on the southern bank of the Humber towards the end of the 9th century. Reputedly, 'Grimsbye' was the point of disembarkation for the first Danish invasion fleet to arrive on British shores.

The most frequently documented references to the history of Grimsby take their origin from ‘The Lay of Havelok the Dane'. This poetical tale, the earliest known version of which dates back to 1170, some 834 years ago, tells the tale of a Danish fisherman named Grim, who legend says was responsible for the founding of the settlement of Grimsby.

Grim is alleged to have come to the area and settled at a point where the local river Haven entered the Humber estuary, and here at 'Haven's lock' he formed the 'village of Grim'. The Haven was so named because it formed a natural haven for boats to shelter from the storms, and as news of the settlement spread, more Scandinavians came to the area from across the North Sea, integrating well with the local people; the village became a thriving centre for fishing. The newly naturalised Scandinavians traded their produce with other towns and villages to the north and south of the Humber area, as well as across the sea to nearby France and Flanders.

The truth of the tale of Grim is like most historical narratives, open to conjecture. Havelok, a hero of medieval romance, was the orphan son of Birkabein, the King of Denmark. Amidst the complexity of Danish medieval politics, the young boy Havelok was cast adrift on the sea by his evil and treacherous guardian Godard, and doomed to a watery grave. This unpleasant fate was infinitely preferable to that of Havelok's two young sisters. Godard cold-bloodedly cut the throats of the fledgling princesses.

Legends tells us that a raft bore Havelok to the coast of Lincolnshire, where the fisherman Grim found and adopted him, raising him as his own son. Havelok in turn discovered the truth of his heritage, and married Goldburga, the princess daughter of King Athelwold of England, who lived in nearby Lincoln as a ward of Alsi the King of Lindsey. Havelok eventually returned to his homeland, where he became king of both Denmark and of the part of England held in trust by King Alsi for Goldburga. Havelok is reputed to have helped Grim distribute and sell fish; by virtue of his phenomenal strength, he could manhandle enormous fish baskets that were beyond the strength of ordinary men. When a period of drought and famine forced Havelok to seek work further afield, he joined the court of Alsi, the King of Lindsey, at Lincoln as a porter and scullion in the royal kitchens. He soon became renowned for his feats of strength. King Alsi, the ward of his niece, Princess Goldburga, had promised to marry her to the strongest and fairest man in the land. At a stone-throwing contest, Havelok managed to lift one great stone higher and hurl it further than anyone else, and thus he won the hand of his wife. The Havelock Stone sits outside the Welholme gallery in Grimsby, though whether this is the very stone reputedly thrown by Havelok to win the hand of Goldburga is for romantics to believe. In the fullness of time, King Havelok is said to have financially rewarded the ageing Grim for his kindness, and with this money the fisherman built Grim's town or Grimsby. A statue of the fisherman Grim stands today in the grounds of the Grimsby College of Technology at the Nuns Corner junction of Weelsby, Laceby and Scartho Roads.

Many scholars place ‘The Lay of Havelok the Dane' at the end of the 13th century, between 1280 and 1290, a fact supported by a surviving transcript of the poem held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. References to Havelok abound locally – for instance, Havelock School.

The settlement of Grimsby, conveniently sited at the confluence of the river Haven and the Humber, rapidly prospered as a fishing centre and as a centre for commerce. The town gets a mention in the Normans' Domesday Book of 1086, where it is named, alongside the nearby village of Swallow, as being a part of the lands belonging to Ralf de Mortemer. De Mortemer, Drew de Beurere and the better-known Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the half brother of William the Conqueror, were the biggest landowners in a region which at that time boasted a gallant population of just eighty-seven householders.

Grimsby prospered, and was to grow considerably. By the advent of the 12th century, the town’s population was between 200 and 250 souls, and an Augustinian abbey had been founded. In 1114, Henry I (who reigned from 1100 to 1135) granted St James's church to Robert Bloet, Bishop of Lincoln – it had previously been held by Osbert the Sheriff. Henry I also founded Wellow Abbey on the outskirts of the town. By the time Henry II took to the throne in 1154, the town had grown to become the twelfth largest in the country in commercial importance when assessed according to the level of taxes due to the crown.

Grimsby was respected as a port, and it was an established market town that could boast not one but two churches, as well as a mill and a ferry. It is therefore not surprising that King John granted Grimsby a royal charter in 1201. This was one of the oldest such charters in Britain, and with it the town was permitted to run an annual fair, and to manage its own court and local government. By 1218 prosperity had further enlarged the population to some 1,500 to 2,000 souls, who by now included the town's own mayor.

By this time, international trading links were still strongly connected to the Scandinavian countries. In 1230, the main trading cargoes from Norway included pine and boards, the beginning of the timber trade that has continued as a staple of commercial Grimsby docks traffic for 800 years to date. Other imports included wines from France and Spain, whilst coal was transported down the east coast from Newcastle. The main export was grain from the Lincolnshire regions and wool.

Underlying these enterprises, the rich fishing grounds of the North Sea provided a seemingly endless bounty.

By the 1920s Grimsby had grown into the largest and most prosperous fishing port in the world. A huge tonnage of cod, haddock and herring from the North Sea and the Icelandic fishing grounds was processed in the town to supply the length and breadth of the nation. During the inter-war years there was exceptional growth of the steam trawler fleets based in both Hull and Grimsby. These ships, with their port registration letters ‘H’ for Hull and ‘GY’ for Grimsby, are seen in many of the photographs of the docks at this time. It is an astonishing fact that Grimsby alone, from this time and until the mid 1970s, provided one fifth of all the fish consumed in the UK. The eventual decline in the industry came as a result of the fishing limitations that Iceland placed on their fishing ground, which resulted in the aptly named ‘cod wars’ of the 1970s. The outcome was a huge decline in fish landings and the eventual loss of the deep sea trawling fleet - the Grimsby fishing industry was decimated. Fortunately though, Grimsby people adapt. Smaller shallow-water seine fishermen took over, and with a substantial fresh fish processing and cold storage facility in town, fish was still brought overland to Grimsby for sale and processing. The overall difference in fish tonnages passing through Grimsby is much reduced, but it has not spelt a death knell for the docks.

In recent years the Grimsby and Cleethorpes region has become one of the big commercial success stories, and the area has enjoyed unprecedented levels of inward investment. For several consecutive years the massive twin ports of Grimsby and Immingham have been confirmed as the largest and busiest ports in the UK. Internationally they are the sixth busiest port complex in Europe, whilst Immingham alone is the second busiest ferry terminal in the country. Over 10% of the nation’s foodstuffs passes through the ports each day. Grimsby has set a standard as Europe’s food capital, which keeps the docks especially alive and flourishing, and trade in Grimsby’s £14 million state-of-the-art fish market is busy. Grimsby is now both the UK centre for buying, selling and freezing fish, and one of Europe’s premier fishing and fish processing centres, with the largest frozen storage capacity in Europe.

Appropriately for a place with such a strong fishing tradition, the multi-award-winning National Fishing Heritage Centre opened at the Alexandra Dock Grimsby in 1991. The trawler ‘Ross Tiger’, which is moored outside the centre, is an excellent reminder of the proud heritage that built the town.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Grimsby History in Photos

More Grimsby PhotosMore Grimsby history

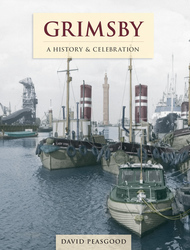

What you are reading here about Grimsby are excerpts from our book Grimsby - A History and Celebration by David Peasgood, just one of our A History & Celebration books.