Sheffield History

The history of Sheffield and specially selected photographs

Sheffield began life as a town rather than a village under its Norman lords. When the Norman lords and their retinues entered South Yorkshire shortly after their success at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, they were entering an area that was heavily settled and peopled. We know this from the Domesday Survey, conducted 20 years later in 1086 by William the Conqueror to find out about ownership of the land before and after the Conquest, and to determine the value of each property (called a manor). Although there are some notable omissions, what the Domesday Survey did was to record many places for the very first time. In what was to become the parish of Sheffield, Sheffield itself, Hallam (recorded as Hallun), Attercliffe and Darnall were recorded for the first time, as was Grimeshou, later changed to Grimesthorpe. In neighbouring Ecclesfield parish, which together with Sheffield parish became known as Hallamshire, besides Ecclesfield itself the Domesday Book also recorded Holdworth above the Loxley valley, Ughill, Worrall and what today is the tiny hamlet of Onesacre. But 16 berewicks (dependent small settlements within a manor) in Sheffield manor, which were said to exist in the survey, were tantalisingly left unnamed. Other places beyond Hallamshire but now within the city boundaries were recorded in the Domesday Survey. These include Tinsley, which was incorporated into Sheffield in 1921, and the villages formerly in Derbyshire: Beighton, Mosborough, Norton, Totley, and Dore, the latter name being recorded as early as AD 828.

The Norman town was established immediately to the south-west of the confluence of the rivers Don and Sheaf where, in the 12th century, William de Lovetot built a motte and bailey castle with a stone and timber keep, possibly on a site continuously occupied since at least the Iron Age. Excavations carried out on the castle site in the 1920s found not only the remains of a timber-framed Saxon building but also Roman pottery. The two rivers formed a natural moat to the Norman castle on the north and east. This motte and bailey castle which had descended to the de Furnival family at the end of the 12th century was destroyed by fire in the second half of the 13th century during the baron’s revolt and was replaced by Thomas de Furnival with a stone keep and bailey castle about 1270. This stone castle was largely demolished in the late 1640s by Cromwell’s government following the Civil War, when it was garrisoned for the king until it surrendered in 1644. Following its demolition it was plundered by the local population for building stone, and other buildings occupied the site. For these reasons precise details of its layout have not survived. The excavations carried out in the late 1920s - when the Brightside and Carbrook Co-operative Society was building new business premises on the corner of Waingate and Exchange Street, and Sheffield Corporation commenced building work on the Castle Market site - revealed stretches of stone wall, a circular bastion next to the main gateway, possibly part of the gatehouse and its drawbridge support and many interesting medieval artefacts in what had been the moat. At its greatest extent this outer bailey is thought to have run south from the moat up the slope as far as the modern Fitzalan Square.

The medieval market town of Sheffield grew up under the protection of the castle. In 1281 Thomas de Furnival was asked by a royal enquiry into the rights of landowners on what grounds he believed he had the right to hold a market in Sheffield, and he replied that his ancestors had held it since the Norman Conquest. He put this right to hold a market on a more formal footing 15 years later when in 1296 he obtained a royal charter for a market every Tuesday and a fair at the Feast of Holy Trinity, which fell in either May or June.

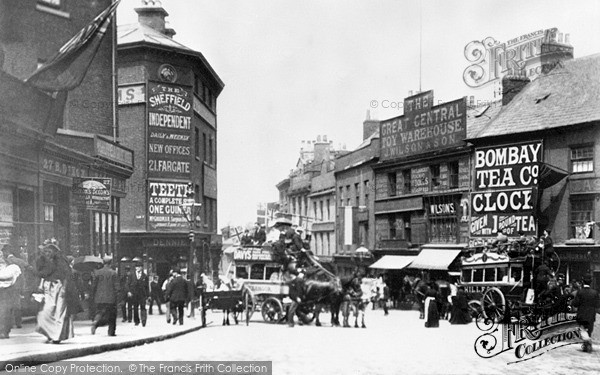

Beneath the castle walls, in a tight cluster of narrow streets including what is the modern Market Place, Haymarket (formerly called the Beast Market and before that the Bull Stake), Waingate (formerly called Bridge Street), Castle Green, Castle Folds, Dixon Lane, Snig Hill, and the now lost Pudding Lane, Water Lane and Truelove’s Gutter (which was also an open sewer), lay the oldest part of the town which had probably first emerged at the same time as William de Lovetot’s motte and bailey castle. Surviving documents from the late 16th century give the impression, 500 years after its first creation, of a tightly knit collection of houses, cottages and shops with their outbuildings, gardens, crofts and yards.

Before the 17th century all the houses in the town would have been timber framed. A detailed set of accounts has survived relating to the building of a new house for William Dickenson, the agent for the Earl of Shrewsbury’s Sheffield estate. The accounts give details of 16 trees that were purchased and payments that were made for ‘posting’ the timber (ie squaring and preparing joints in the main timber components), ‘leading’ the posts and beams from the wood to the house site, ‘rearing’ the house (ie lifting and securing the timber framework in position) and ‘dawbinge’ (ie covering with a mixture of straw and clay the panels between the vertical timber posts, which would have been filled with wattle or very thin stone slates). On the day the house was reared Dickenson spent the relatively large amount of 48 shillings and 8 pence on ale to celebrate the occasion.

The central area immediately to the south and west of the castle was the town’s main retail area. Here too was the market cross and the Bull Stake where the town bull may have been tethered for hire. In nearby Pudding Lane, a narrow lane between the Market Place and the Bull Stake (Beast Market), was the public bakehouse where, as late as 1609, one of the ‘paynes’ (by-laws) agreed by a jury at the manorial court stated that all the householders within the town of Sheffield should bake their bread there.

From this central core beneath the castle walls, the town spread out in all directions. To the east along what became known as Dixon Lane the way led to the River Sheaf where a stone bridge was built in 1596 and which led to the castle orchards. To the south-west the town spread along what is the modern High Street but until the late 18th century was known as Prior Gate because it contained properties belonging to Worksop Priory that had provided a vicar for the church in return for one-third of Sheffield’s tithes. Beyond High Street was a lane that became known as Fargate (gate (gata) being the Danish Viking word for a lane). Along both sides of High Street and the southern side of Fargate today can still be seen the evidence of the late medieval and early modern expansion of the town in the form of long narrow building plots sometimes separated by long alleys such as Change Alley, Mulberry Street and Chapel Walk.

No account of early Sheffield would be complete without describing the beginnings of its staple industry, the light steel trades, which sustained its growth and prosperity for centuries.

No one knows when the light steel trades of Sheffield were born. The oft-quoted 13th line of Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Reeve’s Tale’ in his ‘Canterbury Tales’ - ‘A scheffeld thwitel baar he in his hose’ suggests that in the late 14th century (‘The Canterbury Tales’ were written between 1387 and 1400) the author believed that reference to ‘a pointed Sheffield knife’, used for cutting and spearing food and kept in a sheath at the waist, would be as familiar to his readers then as a Melton Mowbray pie or Harrogate toffee would be today. If this is the case, then it can be confidently said that in the late 14th century Sheffield already had a national reputation for its cutlery manufacture. There is a reference as early as 1297 in the tax returns of Robertus le coteler - Robert the cutler of Sheffield. By the late 14th century, about the time that ‘The Canterbury Tales’ were being written, there were a good number of references to cutlery making and allied trades. In the poll tax returns of 1378-79 for Sheffield and Handsworth, for example, 20 smiths were listed together with three taxpayers, Thomas Byrlay, Johannes atte Well, and Thomas Hank, who were specifically described as cutlers. In neighbouring Ecclesfield six smiths were listed, together with Ricardus Hyngham, ‘cutteler’ and Johannes Scot, ‘arismyth’ (arrowsmith).

By Elizabethan times the town had overtaken its provincial rivals at Thaxted in Essex and Salisbury in Wiltshire and lay second only to London in cutlery manufacture. The term cutlery embraced not only the making of knives but also other articles with a cutting edge such as scissors, shears, sickles and arrows (but not forks which until the second half of the 17th century were regarded as an Italian, and somewhat feminine, affectation). There are several convincing literary references to the importance and reputation of Sheffield’s cutlery manufacturers. For example John Leland, the topographical writer who visited Sheffield in 1540, wrote that ‘Ther be many smithes and cutelars in Hallamshire’. And in 1569, the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury wrote to Lord Burghley, Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, informing him that he would be receiving ‘a case of Hallamshire whittells, being such fruictes as my pore cuntrey affordeth with fame throughout this realm’.

As the cutlery trades of Sheffield and its surrounding area developed rapidly in the 16th century they came under the regulation of the manorial courts, which dealt with matters such as apprenticeships, the issuing of trade marks, the drawing up and supervision of work practice regulations and the settlement of disputes. There was, therefore, an organisational, and in many respects restrictive, framework within which the growing industry operated, together with the personal interest and patronage from successive lords of the manor, particularly from the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (lord of the manor between 1560 and 1590), and the 7th Earl (1590-1616) under whose lordship new and more detailed ordinances were drawn up in 1590. The first marks known to have been recorded were in 1554 and by 1568 about 60 marks had been registered.

This organisational framework nurtured an industry which was based firmly on the exploitation of the local resources of coal measure ironstone from which the earliest metal articles were made, and easily reached shallow coal seams and charcoal (from the large number of managed woods throughout the manor) for smelting and smithing fuel. Grindstones from the coal measure sandstone quarries were also available for putting the cutting edge on the finished articles. And, most importantly, many water-powered sites could be created on the fast flowing Don and its tributaries to power the forge hammers and grinding wheels. These local resources were supplemented by better-quality imported steel in the 16th century from northern Spain and in the 17th century from central Europe via the Rhine and the Baltic coasts of northern Germany, and from Sweden.

‘… the most remarkable place in England for cutlerywares…’ – this was the tribute paid to Sheffield by Charles Burlington in ‘The Modern Universal British Traveller’ in 1779. The reputation of Sheffield for its cutlery and edge tools grew and grew throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and by the early 19th century it had an international reputation second to none.

The first great industrial step forward took place in 1624. In that year the cutlers of Sheffield presented a successful bill to Parliament. The bill – ‘An Act for the Good Order and Government of the Makers of Knives, Sickles, Shears, Scissors and other Cutlery Wares, in Hallamshire, in the County of York, and the parts near adjoining’ - was passed by the House of Commons in April and by the House of Lords in May. Thus the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire came into being. At the time of the passing of the Act there were 498 master craftsmen in Hallamshire: 440 knife makers, 31 shear and sickle makers and 27 scissors makers. Later in the century other specialist craftsmen were admitted and in 1682, when there were over 2,000 master craftsmen who had become members of the ‘communality’, they included scythe makers, file smiths and awl-blade makers. By the mid 17th century some 60% of working men in Sheffield worked in the cutlery trades. Many of these workmen were ‘little mesters’ who ran their own businesses with the help of apprentices and journeymen (workers who had completed their apprenticeships but had not set up their own firms) from small workshops attached to their cottages. Here might be a coal-fuelled smithy where blades were forged or small rooms where the handles were fitted or ‘hafted’ and where knives were finally assembled after the blades had been taken to a riverside cutlers’ wheel to be ground on a grindstone. Some cutlers might specialise in forging, grinding or assembling.

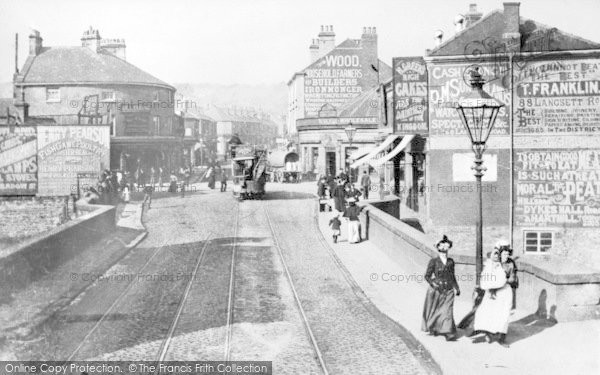

Sheffield has been famous since the 14th century for making cutlery, but it was local clock maker Benjamin Huntsman’s discovery in the 18th century that steel could be purified by using a crucible that led to Sheffield becoming the steel capital of Britain. Forges, metal-working shops and steelworks in the area came in all shapes and sizes, from those employing just a handful of men to the industrial giants like Firth Brown and Hadfields. There were other important industries in Sheffield too, such as the Yorkshire Engine Co, which built railway locomotives, and there were also several collieries within easy reach of the city centre.

Sheffield was badly damaged during the Second World War, particularly on the night and early morning of 12-13 December and the night of 15 December 1940. There was heavy damage to property, with 2,849 houses being totally demolished. Civilian deaths amounted to 668 and another 513 were seriously injured. Following the wartime devastation much of the city centre was rebuilt. Little now survives of the pre-Victorian era, save for parts of the cathedral and a handful of houses.

In the second half of the 20th century foreign competition in the cutlery industry was affecting Sheffield’s trade, not only from the traditional rivals of the USA, France and Germany but also from the Far East and South Korea. The crash came in the 1970s, and most of Sheffield’s great names disappeared. Viner’s, the largest cutlery firm in the country, went out of business in 1982; its name and trademark were sold, and now they appear on imported Korean cutlery. The silver and electro-plate companies fared no better, and the workshops and factories of many of the traditional old Sheffield companies have been demolished, or converted for new uses. Sheffield’s heavy steel industry also went into severe decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Employment in the steel works in the Lower Don Valley declined from 40,000 in the mid 1970s to 13,000 ten years later.

However, the lower Don Valley was rejuvenated in the closing years of the 20th century. It now contains, for example, a renovated canal basin (renamed Victoria Quays), a technology park, the Don Valley Stadium (the biggest athletics stadium in the country), the Arena which holds 12,000 people, and the Meadowhall shopping centre with 270 stores and parking for 12,000 cars.

‘Smoky Sheffield’ is now a thing of the past. The 21st-century city prides itself on being an attractive and confident place in which to live and work. After the decline of its traditional industries in the 1970s and 1980s, Sheffield has now turned the corner with a much more varied economy and with large parts of its townscape regenerated and renewed. The £130m Heart of the City scheme is revitalising Sheffield’s city centre. It has already seen the opening of the Millennium Galleries, the Winter Garden and the re-designing of the Peace Gardens, and the transformation of the entry into Sheffield outside the railway station by the creation of a new public plaza with water features and a 90m-long steel sculpture representing a knife blade will ensure that the city’s proud industrial heritage is never forgotten.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Sheffield History in Photos

More Sheffield PhotosMore Sheffield history

What you are reading here about Sheffield are excerpts from our book Sheffield - A History and Celebration by Melvyn Jones, just one of our A History & Celebration books.