Stirling History

The history of Stirling and specially selected photographs

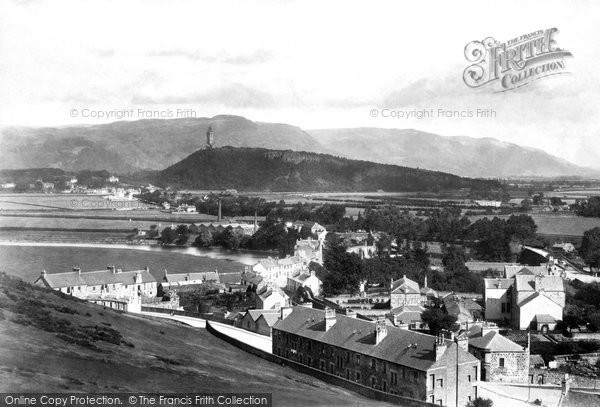

Sometimes described as ‘the brooch which clasps the Highlands and the Lowlands together’ and the ‘gateway to the Highlands’ because of its strategically important position between the Scottish Lowlands and Highlands, the city of Stirling is clustered around one of Scotland’s greatest royal fortresses, Stirling Castle. It was there that both James II and James V were born, and where Mary, Queen of Scots and James VI both lived for a number of years – in fact, Mary was crowned in its Chapel Royal.

Stirling is the last place where there is a bridge over the Forth before the river widens into a tidal estuary with ferocious currents. Anyone coming from or to the Highlands would almost certainly cross the river here. Consequently, Stirling, its castle and its bridge have been fought over on numerous occasions through history, and Stirling Bridge was the site of one of the most important battles in Scotland’s story. In 1296 the English king Edward I, ‘the hammer of the Scots’, invaded Scotland to assert English control, sparking off the Scots’ long battle for independence and freedom from English rule. A confident English force led by John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, and Hugh de Cressingham, Edward’s treasurer, marched north in 1297 to find themselves on the south bank of the Forth, facing the Scots, led by William Wallace and Andrew de Moray, on the northern side of the river.

It was from a commanding position on the slopes of Abbey Craog that Wallace launched his attack against de Warenne’s troops as they attempted to cross the narrow wooden bridge that then spanned the Forth – it was only broad enough to let two horsemen cross at a time. Wallace held back until about half the English force, cavalry and infantry as well, had crossed. Then he sent his spearmen rapidly down to hold the bridgehead and separate the two halves of the English force. The heavy cavalry were bogged down in the marshy ground by the bridge and cut to pieces, and then the Scots fell on the English infantry. English losses were high, and many of the foot-soldiers threw off their armour and swam back to the river – or drowned. Cressingham fought on until he was cut down. De Warenne had stayed south of the river, and he still had command of a large force of archers; he could have held a strong position there and denied the Scots access to their territory across the Forth. But his confidence was shattered, and he retreated south, leaving the triumphant Scots to regain possession of Stirling Castle. The Battle of Stirling Bridge was their first decisive victory in their long struggle for independence.

Stirling Castle sits on a commanding and strategic position on top of a crag with cliffs on three sides, and is one of Scotland’s largest and most important castles, both defensively and architecturally. Nearly all the castle buildings seen today were built between 1490 and 1600, at the time when it was an important royal residence of the Stewart kings James IV, James V and James VI. The architectural style derives from that of England and the Continent – the Stewarts wanted their palace to reflect Scotland’s international importance. Several of James V’s masons, for instance, came from France, and two were Dutch. The Great Hall (or Parliament Hall), one of the first examples of Renaissance architecture in the country, which was built for James IV and completed in 1503. Over the next 100 years it bore witness to feasts, banquets and two sessions of the Scottish Parliament. It is the largest great hall in Scotland, and has been described as ‘the greatest secular building erected in Scotland in the late Middle Ages’.

In the 19th century Stirling Castle became a military barracks (and is seen in this role in the Frith photograph 44697 in the Stirling selection) and the Great Hall was remodelled; many original features were removed, including its specatular hammerbeam roof. The army left Stirling Castle in 1964 and the historic Great Hall has now been fully restored to its medieval glory. A feature of its interior is the magnificent new oak hammerbeam roof, which was constructed without a single nail. The exterior of the hall has also been ‘harled’, as it used to be in medieval times, with a thick waterproofing layer of lime plaster applied to its surface.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Stirling History in Photos

More Stirling PhotosMore Stirling history

What you are reading here about Stirling are excerpts from our book Britain's First Photo Album by Terence Sackett, just one of our General Interest books.