York History

The history of York and specially selected photographs

York is just less than 220 miles from London, and is located within the boundaries of North Yorkshire in the beautiful Vale of York. The population is 177,350 - a portion of this is made up of the student body that attend the relatively new university. Much of the surrounding area is still very much agricultural; a substantial amount of the economy derives from the food industry as well as from tourism. Once an encampment, and originally built at the confluence of the River Ouse and the River Foss, the city now spans a much wider area on both sides of the two rivers. Until the Industrial Revolution, which largely passed it by, York was once the most important town in the north of England.

In Roman times, York was the principal military base in Britain, and in the 9th century it was the capital of a Viking kingdom. Because of its importance in the scheme of things, some records have survived; these records, along with what has been excavated, have enabled historians and archaeologists to piece together a vast amount of York's past. Its rich history spans more than nineteen centuries. York began in 71 AD as a Roman camp, which was home to some 6,000 soldiers. The Romans named the outpost Eboracum, which is thought to have meant 'a place of yew trees'. The location would have been chosen because the rivers would help protect it from attack; ironically, centuries later, the Vikings used the rivers as their gateway for invasion. Near the soldiers' encampment a civilian town sprang up, which was peopled by the traders and their families who supplied the soldiers with clothing, food and the things necessary to life. One Roman building that still stands is the Multiangular Tower; there is also a column that stands 30 feet high which was found during excavations to the Minster in 1969, lying where it had fallen. The York Civic Trust had it erected in the Minster Yard in 1971. A public house called the Roman Bath Inn has a floor made up of panels of glass where one can look onto the remains of a Roman bath house that was excavated in 1930.

During the Saxon period, Eboracum became known as Eoforwic. This period is the least documented, but we do know that the Saxons were instrumental in the spread of Christianity and established the foundations for many of the churches. In 866 the Vikings invaded, and changed the name of the town to Jorvik. Some of the place names, such as Micklegate and Goodramgate, are inheritances from the occupation, although the Vikings were here for less than a century. As with the Romans, not many of the buildings above ground have survived, but excavations have turned up many well-preserved artefacts. The Jorvik Viking Centre, a huge tourist attraction which brings millions of visitors every year, is built upon the site of an excavated Viking settlement, and the artefacts found here have been used in the museum. Even the Viking rubbish dumps were a treasure trove to the historians: shoes, utensils and bits of clothing that had been discarded all serve to show the Viking way of life. The impression we have formed of these people is of frightening-looking men with huge beards and horned helmets who spent their lives burning, raping and pillaging; but the excavations of their settlements show a different picture. The Jorvik Centre proves that once the Vikings put down roots in an area, they had a settled family life.

During the Norman period, in 1089, a large cathedral was built; many churches were built too, some of which have survived. The 13th century saw building begin on a new cathedral replacing the earlier edifice. The building of the present Minster was spread over a period of 250 years. Recently an enormous amount of restoration work has been carried out all over York. There are approximately 1,000 listed buildings in the city, and about twenty of these are churches. The Georgians and then the Victorians have also left their legacies in many of the wonderful buildings that still remain.

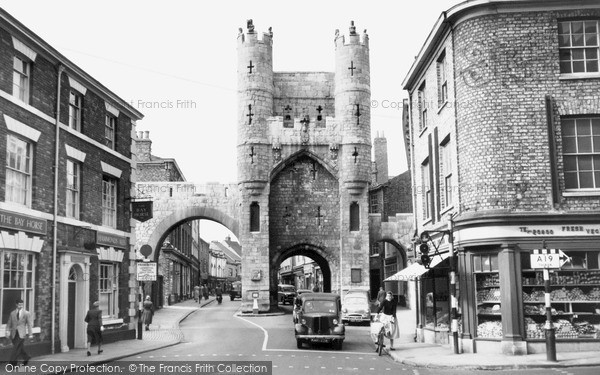

The Romans had built walls spanning nearly three miles in an almost complete circuit around their encampment; chains were stretched across the rivers where they prevented the continuation of the walls. Thus the outpost became a fortress town. The Vikings covered these walls with earth. Then, in medieval times, the walls that still stand today were built on top of the original ramparts with magnesian limestone brought from Tadcaster. The four main entrance gates still survive.

Oil lamps were used until 1824, when gas lighting was introduced to the streets. How the people must have rejoiced to be able to walk the streets in comparative brightness instead of in the murky light of the old lamps. It is said that well over a hundred ghosts can still be seen or heard in the city; the popular Ghost Walks take visitors on a tour of public houses, churches and other buildings as the sad tales behind the hauntings are told. One story is of the Towpath Ghost, a white headless lady who is said to wander up and down the Ouse towpath looking for the people who robbed and killed her while she was strolling along the riverbank. Her body lay hidden for so long that the head had separated from the body. Another story is of children crying; they were supposed to have been killed by the wicked master of a ragged school. Whether one believes in ghosts or not, in a city with such a long and sometimes quite violent history, with so many tears and so much laughter, with so many births and deaths, something must surely remain. Perhaps the spirits of the people that have lived here through the ages are impregnated into the walls and buildings.

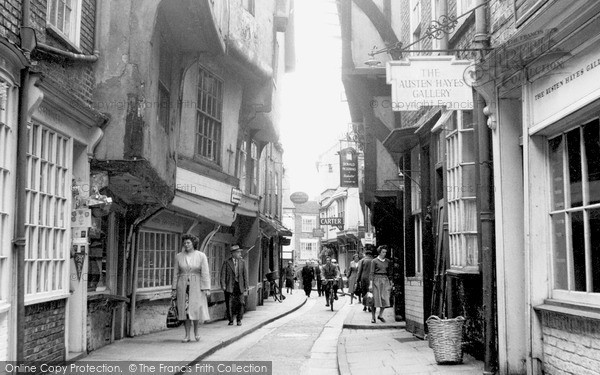

Besides the hauntings, there are many stories of the people who made their mark on York's history, names that will never be forgotten. They include Roman soldiers and emperors, Vikings such as Eric Bloodaxe, and the Dukes of York, six of whom were crowned king; more recently there was Guy Fawkes, who was born here, Dick Turpin, who spent his last days in the condemned cell of the prison, and Margaret Clitherow, who was proclaimed a saint. She was married to a butcher from the Shambles in the 16th century. Arrested for harbouring priests and refusing to plead, she was tried at what was then the Common Hall (now the Guildhall) and sentenced to death by pressing. A house in the Shambles is now set aside as a shrine to her.

Tradition still plays a key role here. At Christmas the high altar in the Minster has mistletoe placed upon it as decoration; the plant said to have magical properties and its associations are pagan, so it is unknown how this practice came to be. Displays of sword dancing are held in St Sampson's Square on Plough Monday, the first Monday after 6 January; again the origins of this custom are unknown - the dancing was once performed by farm labourers. The Mystery Plays are performed in the Minster Yard, usually by amateur groups; 'mystery' derives from the word 'mastery', and all the plays are biblical.

The pride of the city, and one of the most famous buildings in the world, is York Minster, York's cathedral, which was completed in 1472 and restored between 1967 and 1972. An enormous edifice, it boasts wonderful Gothic architecture, woodwork and stonework, and also stained glass, 128 windows in all, spanning 800 years of glass painting. One part of a medieval glass panel shows that the painter had a sense of humour - it depicts what is known as the Monkey's Funeral. A number of monkeys are pictured: the deceased is carried shoulder-high by four pallbearers, while a bell-ringer leads the procession with a cross-bearer behind. The bereaved young monkey is in the centre foreground, being comforted by a friend. Last but not least, one monkey is sampling the wine at the funeral feast. The Minster is still used for daily worship, as well as for services on important occasions. The organ music is known world-wide. Scholars come to study the Minster's history and to use the library, and tourists flock from all over the world to wonder at its beauty.

Although the chimney stacks and the large dull grey buildings relating to heavy industry never made a serious impact on York, the sweet industry made its mark. The origins of Rowntree Mackintosh's and Terry's chocolate empires began in retail businesses in the 18th century. The businesses eventually developed into large-scale confectionery manufacture; in the late 1930s they were employing over 12,000 people. Both these firms are still major players in the confectionery and food industry today. Glass works and instrument-making were also once big business. The coming of the railway had a huge impact, and brought prosperity to many. George Hudson, dubbed 'the Railway King', was instrumental in the development of the railway and its related buildings. He was three times Lord Mayor, but eventually crooked wheeling and dealing with funds brought his downfall; for over a century his name was shunned in York. In recent years, however, his input has been recognised, and a street and a building have been named after him.

There was a long wait for a university in this city, but once plans were approved, work went ahead quite quickly. Some older historical buildings were incorporated into the structure of the plans and the first two colleges were opened in the 1960s, with others following over the next few years.

Such is the wealth of preserved history here, that days rather than hours are needed to tour this amazing city. On turning a corner, beautiful old trees, some older than the buildings, stretch their branches to the sky where you would least expect it.

The ruins of St Mary's Abbey stand in the peaceful, well-manicured Museum Gardens, giving an insight of how harsh life must have been: the thick stone walls and open fires were the only protection from the cold. There is a wealth of medieval stained glass in some of the churches and in many of the buildings, as well as in the Minster. Along the snickelways, we can look above the shop fronts and see public house signs, tea shop signs, statues, carvings, gargoyles and so on - they show what the buildings were once used for or who once lived there. As we walk along the walls, we can see breathtaking views of the rivers and the city. Many buildings that have been preserved or painstakingly restored are open to the public; some are instantly recognisable in this compilation of photographs taken more than a century ago. At dusk many of the buildings are now floodlit. Modern gift shops and cafes now line the little streets, and millions of visitors from every corner of the world tour the city every year, but that does not take anything away from the magical atmosphere - indeed, it seems instead to enhance it. Whatever we do or see here, it gives us an unforgettable experience of a journey back in time.

Just as the tides of the rivers have ebbed and flowed unrelentingly through the ages, so has the history and prosperity of this ancient city. Although the buildings from so many different eras and of differing architectural styles are side by side, somehow they all live together in perfect harmony. They give the impression that here the past merges into the present, and also that the city of York will endure to give pleasure to future generations - and also to teach them that knowing about their heritage can help to shape the future.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

York History in Photos

More York PhotosMore York history

What you are reading here about York are excerpts from our book York Photographic Memories by Maureen Anderson, just one of our Photographic Memories books.