Canterbury History

The history of Canterbury and specially selected photographs

‘Scarce any City is there in this Kingdom, which for antiquity of origins, or for the dignity of its fortune, can be compared with ours.’ (John Twyne, Mayor of Canterbury, 1553-54)

Before the Roman conquest of Britain of AD43, there was a prosperous Iron Age trading town named Durwhern in the Canterbury area, where trackways converged to cross the River Stour as it cut through the Downs. The Romans renamed the town Cantiacorum Durovernum, a Romanised version of Durwhern; the other element referred to the Cantiaci, the tribe of Kent. After the end of Roman rule, the whole of Kent fell to Germanic invaders from the North Sea coast and Denmark. A kingdom of Kent emerged, with Cantwarabyrig, meaning ‘the burg, or defended settlement, of the Kentish people’, as its capital.

During the Roman period, the town of Cantiacorum Durovernum was very important, for here the Roman road now called Watling Street passed on its way from the port of Richborough (the gateway to Britannia) to London and beyond. Roads from two other Roman ports also converged here, one from Dover and the other from Lympne. There were also roads to Reculver and to the port at Fordwich on the River Stour. The town thrived, complete with baths, a forum, an amphitheatre and defensive walls. Canterbury’s Roman Museum has been built around the remains of a Roman town house which was discovered beneath the Longmarket shopping development (the entrance is in Butchery Lane). The house had several rooms and corridors with colourful mosaic floors, and some of these can be seen in the museum.

In the late 6th century Pope Gregory sent a mission to England to convert the Anglo-Saxon people to Christianity. The mission was led by Augustine (later St Augustine). He and his companions landed in south-east England and made for Canterbury, from where King Ethelbert ruled the kingdom of Kent. Ethelbert’s wife Bertha, a Frankish princess, was already a practising Christian and worshipped in St Martin’s Church, which probably dates back to a Christian church here that was founded during the Roman period. Ethelbert was baptised on Whitsunday, AD597. He allowed Augustine to found two monasteries, one outside the city walls, originally dedicated to St Peter and St Paul but which later became known as St Augustine’s Abbey, and Christ Church Priory within the walls. Augustine and most of the Anglo-Saxon archbishops and Kentish kings were buried in St Augustine’s Abbey, while Christ Church Priory became the archbishop’s seat, or ‘cathedra’.

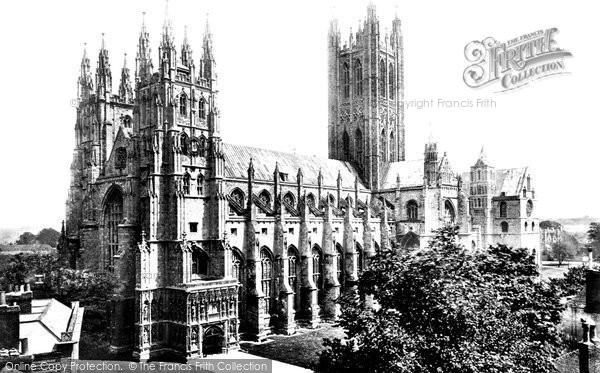

Canterbury is famous the world over for its cathedral. The present building was founded by the Normans in 1070, but the nave was rebuilt to the designs of Henry Yevele between 1378 and 1405 and the central tower, Bell Harry Tower, was added c1500. The earliest Norman work is found in the crypt, the largest Norman crypt in Britain. Canterbury Cathedral has been an object of pilgrimage for many centuries, a pilgrimage immortalised by Geoffrey Chaucer (1335-1400) in his ‘Canterbury Tales’, which depicts a group of pilgrims setting out from Southwark to Canterbury. The object of their journey was the shrine of St Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury famously martyred in 1170 by four of Henry II’s over-zealous knights. Thomas Becket was canonised in 1173, and the shrine of St Thomas rapidly became the destination of one of the three major European pilgrimages; the other two were to Santiago de Compostela in western Spain and to Rome, the mother church in the Middle Ages of all Christendom:

‘And specially, from every shires ende Of Engelond, to Caunturbury they wende, The hooly blisful martir for the seke That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke ..’

The Museum of Canterbury in Stour Street is housed in one of Canterbury’s finest medieval buildings, in what was formerly the Poor Priests’ Hospital (‘hospital’ on those days meant accommodation, or ‘hostel’). The building was at one time also used as a workhouse for the destitute. Amongst the fascinating exhibits in the museum is a collection of medieval pilgrim badges. These badges were usually made of pewter, and were bought by pilgrims in the Middle Ages to show all the places that had been visited, in much the same way as some people nowadays collect souvenir badges from tourist spots. The Canterbury badges usually bore a likeness of St Thomas.

The first castle in Canterbury was a wooden ‘motte and bailey’ castle at Dane John. In the late 18th century the Dane John Mound was created to mark the spot, surrounded by an attractive park. The early castle was replaced by Canterbury Castle, which was completed during the reign of Henry I (1100-1135). This was one of the first castles in England to be built of stone, but its ruined keep off Castle Street, once one of the largest in the country, is all that remains.

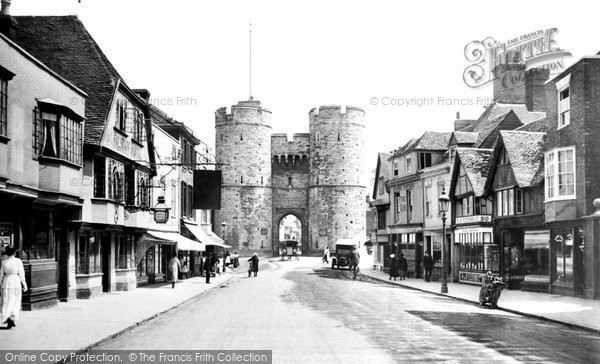

Long stretches (about 1 mile) of Canterbury’s Norman and medieval city walls, built on Roman foundations, are still visible - the best sections can be seen at Dane John and Broad Street. A small fragment of the Roman Queningate can still be seen opposite the Great Gate of St Augustine’s Abbey, and foundations of the Roman wall can be seen at Burgate and Northgate (where a huge length is built into the church of St Mary there). The medieval walls once included 21 watch-towers, many of which have survived, although they have often been incorporated into houses.

From the late 16th century a number of Huguenots and Walloons fled from religious persecution in France and Flanders and came to England, bringing with them their weaving skills, especially of silk. Some of them came to Canterbury, and the Weavers’ House in the High Street (now a restaurant) was the centre of much of their industry. It once housed hundreds of looms and the river below was used in part of the cloth-making process. Some of these Huguenot refugees prospered; they contributed a great deal to Canterbury, and some of them became councillors, including Alderman Sabine, who is believed to have built the timber-fronted ‘leaning house’ at 28 Palace Street, once known as the King’s School Shop; Avery Sabine was a woolcomber and his initials are near the door. Historians believe that the house was built by Sabine to house weavers; the small windows at the bottom of the building were to let in the light as the weavers worked. The house is famous because it appears to be resting on the building next door, and its front door is sharply angled.

The Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe was born in Canterbury, probably in 1564, and educated at King’s School; his father, John, was a cobbler in the city. Marlowe is best known for his plays ‘Tamburlaine the Great’, ‘Edward II’ and ‘The Tragical History of Dr Faustus’, and his poetry, one of the most popular works being ‘The Passionate Shepherd to his Love’. The Marlowe Theatre in Canterbury is named after him. The Marlowe family had a reputation for being loud, boisterous and often at war with their neighbours. One of Christopher’s sisters was known for being a ‘scowld’, but it is not known whether she was ever subjected to the humiliation of Canterbury’s ducking stool over the River Stour near the Weavers’ House. The ducking stool that can be seen there today is a modern replica of the stool used in medieval times to punish nagging women by ducking them in the river. It was also used to test women suspected of being witches by submerging them in the river - if they were guilty they would survive by using their magic powers, but if they were innocent they would drown.

Canterbury was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe in 1942 during the ‘Baedeker raids’ of the Second World War; these were air raids deliberately aimed at some of the most historic British cities, chosen from the Baedeker guide books, and were an attempt by the Germans to lower British morale. The cathedral suffered some damage, but the bombs destroyed a great deal of the city itself. However, one result of the damage was that much of Canterbury’s Roman foundations were discovered during reconstruction work, and much more is now known about the city’s earliest years.

Despite the damage suffered both by war and modern development, Canterbury still contains many ancient buildings. Nowadays the pilgrims to the city take the form of modern tourists, who flock here in their thousands each year to soak up the atmosphere of this holy and historic place.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.