Newcastle upon Tyne History

The history of Newcastle upon Tyne and specially selected photographs

The settlements that have developed around the mouth of the River Tyne lie in an area steeped in history, which was once part of the powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria; but in around AD120, centuries before the Anglo-Saxons came here, Roman soldiers were building a great defensive wall out of stone and turf that spanned the entire width of Britain from Bowness on the east coast to Wallsend on the west, a distance of 73 miles. What is now known as Hadrian’s Wall was created to prevent military invasions from the north by the Pictish tribes of the north. It was the northern border of the Roman Empire in Britain for hundreds of years, and was certainly the most heavily defended fortification in the Empire. Surviving sections of Hadrian’s Wall can be seen on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne, at Denton, on the A69.

The Roman name for Newcastle was 'Pons Aelius'. There was a Roman bridge here; ‘Pons’ means bridge, and ‘Aelius’ was the family name of the emperor who gave his name to Hadrian’s Wall, so the name can be translated as ‘The Bridge of Hadrian’.

The original New Castle on the Tyne was built by Robert Curthose, the brave but short tempered and headstrong eldest son of William the Conqueror, on his return from campaigning against Malcolm III of Scotland. It was a motte and bailey: a wooden tower on a mound was protected by a ditch on its west side and by precipitous banks on the other three, and it was from this fortification that Newcastle would derive its name. This castle was replaced by a stone castle in the late 12th century.

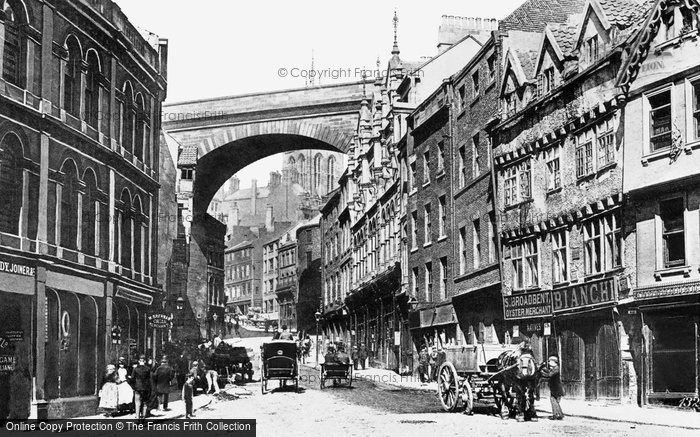

Medieval Newcastle was protected by a town wall with six main gateways: Sand Gate, West Gate, New Gate, Pandon Gate, Pilgrim Gate, and Close Gate. Along the wall were seventeen towers, and there were also a number of small turrets between the towers and gates which acted as lookout posts. The 16th-century antiquarian John Leland was most impressed with Newcastle’s defences, describing them as ‘far passing all the waulls of the cities of England and most of the cities of Europe’. Today the best surviving section of the old town wall to be seen is to the west of the city centre in the vicinity of Stowell Street; the remains of four towers may also be seen along this section of the defences. There is a smaller section of wall near Forth Street behind the Central Station, but nothing has survived of the walls to the north of Newcastle, and only three isolated towers remain to the east.

In the vicinity of City Road you can see the remains of one of the seventeen towers that guarded the town wall around medieval Newcastle. This tower has a small gateway called the Sally Port - the gateway from which the defenders of Newcastle would ‘sally forth’ out of the town against the enemy.

St Nicholas’s Church in Newcastle was the fourth largest parish church in England until it became a cathedral in 1882, when Newcastle was awarded city status. A small part of the cathedral is late 12th-century, but most of the architecture is from the 14th and 15th centuries.In St Nicholas’s Cathedral in Newcastle is a magnificent memorial brass of 1441. It is one of the largest in the country, and commemorates Roger Thornton and his wife, Agnes, and their many children - seven sons and seven daughters. Roger Thornton was a ‘Dick Whittington-style’ self-made man who arrived in the town with nothing, but when on to become a successful merchant; he was also Lord Mayor of Newcastle three times. A local rhyme said:

‘In at the Westgate came Thornton in with a happen hapt in a ram's skin.’

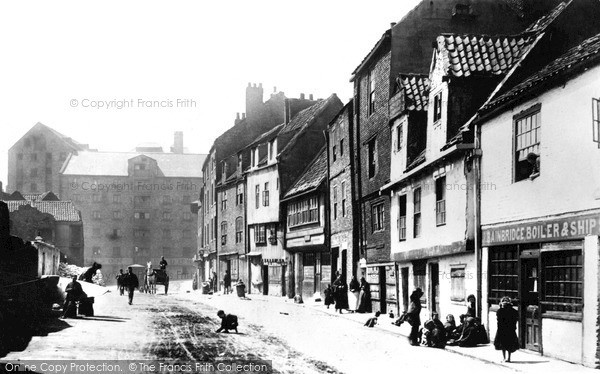

Agriculture, fishing and coalmining provided a livelihood in the area for many centuries. Newcastle's port developed in the 16th century and Charles I ensured Newcastle’s prosperity when he granted the town the east of England coal trading rights, but this monopoly was to the detriment of nearby Sunderland, and the Tyne-Wear rivalry that ensued still exists. At the western end of the Newcastle quayside is a street called Sandgate. This street was the area where the keelmen lived. The keelmen were unique to the Tyneside region. They were highly skilled boatmen, who handled the movement of coal from the riverside to the ships waiting on the Tyne. The keelmen took their name from their small vessels, called keels, which could carry around 20 tons of coal. The first recorded use of keels for transporting coal on the Tyne comes from the early 1300s. The keelmen thought of themselves as a separate community, and wore a distinctive blue jacket, along with a yellow waistcoat, flared trousers and a black silk hat tied with a ribbon.

In the 18th century Newcastle became an important print centre, ranking with London, Oxford and Cambridge; the Literary and Philosophical Society of 1793, with its debates and large stock of books in several languages, predated the London Library by 50 years. Newcastle also became an important glass producer, and there was a rope-making industry here.

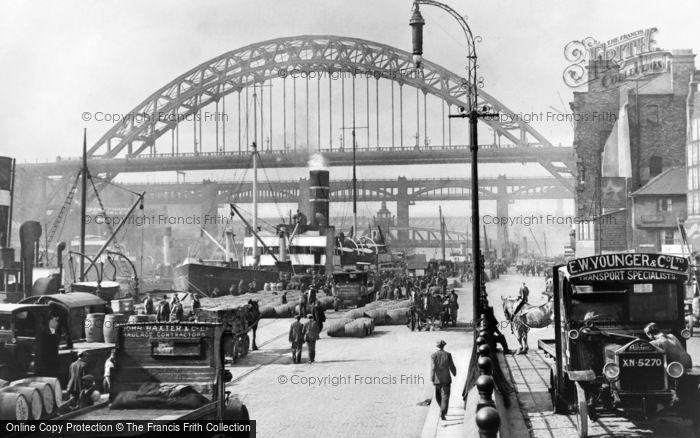

However, Tyneside really boomed in the 19th century, becoming the industrial and commercial capital of the north-east, its wealth stemming from coal, iron and steel. Newcastle, along with the shipyards lower down the river, was amongst the world's largest shipbuilding and ship-repairing centres. The shipbuilding industry around the River Tyne employed thousands of people. At the beginning of the 20th century British shipyards were at the forefront of both world shipbuilding and ship repairing, and could build a battleship twice as fast as any American yard, and five times faster than the embryonic Japanese shipbuilding industry. In its heyday, Tyneside was a hive of heavy industry. There were dozens of coalmines working, shipyards lined the banks of the Tyne,The economic depression of the 1930s caused a rapid decline in shipbuilding business and hit the area particularly hard, resulting in high levels of unemployment and great hardship.

There is a long tradition of markets in Newcastle. Some of the historical markets gave their names to parts of the city centre, such as Hay Market and Bigg Market (bigg was a form of barley); other markets were the Herb Market, the Cloth Market and the Butter Market. Paddy’s Market was for second-hand clothes, and was so popular that it has given its name to a local phrase to describe somewhere busy and crowded: ‘It’s like Paddy’s Market!’

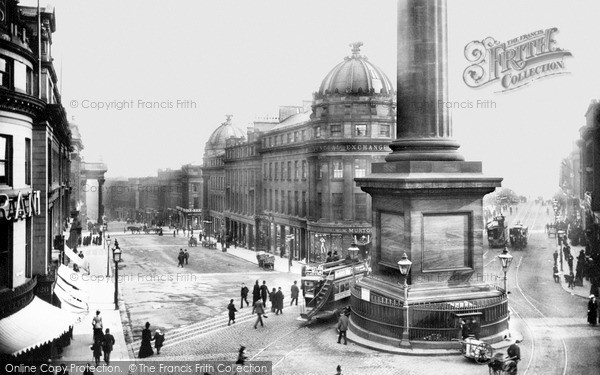

The imposing monument in Grey Street is a major landmark of Newcastle. It commemorates Earl Grey (1764-1845), who was the MP for Northumberland for more than 20 years and also the Prime Minister who masterminded the Reform Bill of 1832. This important piece of legislation gave seats in Parliament to the new towns created by the Industrial Revolution, and also extended the franchise. It was a reform that had been strongly resisted by the more reactionary element of British society, and was achieved after over 50 years of agitation from people who felt that those who were creating the wealth of the country should be represented in its Parliament.

Grainger Street in Newcastle is named after one of the three prominent 19th-century citizens who were responsible for much of the town centre. Richard Grainger and John Dobson supplied the architectural talent, and John Clayton the money and influence. These men planned and built one of the finest town centres in England, favouring the elegant and graceful Classical style instead of the Gothic Revival that was so fashionable with other Victorian architects. Their choice has stood the test of time.

When the late 18th-century bridge over the Tyne at Newcastle was demolished in the 1870s to make way for the Swing Bridge, traces of an earlier medieval bridge (destroyed by flood in 1771) and a Roman bridge were discovered. The Swing Bridge cost £228,000 to build. It has an overall length of 560ft; the swing section is 281ft, giving two navigable channels each 104ft wide. The superstructure was designed and built by Sir W G Armstrong at Elswick and was floated into place.

The Gateshead Millennium Bridge, a foot and cycle bridge spanning the River Tyne between Newcastle and Gateshead, was lifted into place in November 2000 by one of the world’s largest floating cranes, and was opened to the public on 17 September 2001. The bridge, which cost £22 million to build, has become a tourist attraction renowned for its elegance and beauty. Huge hydraulic rams on each side of the bridge allow it to tilt back on special pivots, allowing river traffic on the Tyne to pass underneath. This manoeuvre has led to it being nicknamed the Blinking Eye Bridge.

Attached to the exterior wall of Newcastle’s Civic Centre is a bronze figure that represents the River God of the Tyne; his head is bowed and a stream of water flows from his raised right arm. The figure was created in 1968 by David Wynne, and is his interpretation of a stone carving of a figure of the Tyne River God dating from 1786 on the wall of Somerset House in London. The original figure, which was part of a series of eight carvings representing the most important rivers in the country, had fish tangled in his hair and held picks and baskets of coal, which represented the trade and industry of the Tyne in the late 18th century. Nowadays, ‘Canny Newcassel’ looks forward into the 21st century as a vibrant, exciting and modern commercial city.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.