Basildon History

The history of Basildon and specially selected photographs

Destruction and regeneration are common themes. They occur in several mythologies - the Biblical flood and the Germanic Twilight of the Gods are examples that spring readily to mind. The context is generally the same: an old world, having become unworkable, is destroyed by water or fire and replaced by a gleaming new Utopia. In mythology, it is all very clear-cut. Everything is black, white, green or gold.

It is improbable that Teutonic myth was foremost in the mind of the Rt Hon Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town & Country Planning, as he stood in Laindon High Road School one October night in 1948. Nevertheless, there were parallels. The old world was a sprawl of cottages and sheds - dwellings that were being described as 'sub-standard'. The deluge, if it came, would not be of fire and water, but of mud and, many predicted, tears. The Minister was in Laindon to persuade the town's understandably horrified freeholders to sacrifice their homes for a better, brighter future. In fairness, no-one had expected his task to be an easy one.

Basildon has an unusual history. The majority of towns just seem to happen. Of course, they are subject to changes in economics, technology, geography, and the social climate; but change is seldom wholesale. The town we now call Basildon, however, is rather different, in that it was created very deliberately. And it happened not once, but twice. At the start of the 19th century, Basildon was a small parish with a negligible population. It was bounded on the west by Laindon, Dunton, Langdon Hills and Lee Chapel; on the south and east by Vange, Pitsea and Nevendon. All were quiet, agricultural places - but those days were numbered.

The problem lay in the stodgy London clay that characterises this part of Essex. Always a devil to plough, the farmers used to call it 'three horse land'. Cheap grain was starting to be imported from America, and what with some poor harvests in the 1870s, an agricultural depression was soon underway in England. The writing, it seemed, was on the barn wall. Land was being put to new uses. Out on the coast, farming and fishing villages were reinventing themselves as new-fangled watering-places. Southend was Essex's prime example. There had been a meandering railway line connecting Southend to London since the 1850s, but it was the building of a second, more direct line that affects our story. Completed in 1889, it cut straight across the Basildon area, re-joining the older line at Pitsea Junction.

With south-east Essex suddenly accessible, and farmland falling out of cultivation, something was bound to happen. It did. From 1885 onwards, land-agents had been acquiring the disused fields and offering them for sale as building land. After a few false starts, they hit upon the idea of carving the land into minuscule plots, roughly 18 ft wide, and offering them to buyers of fairly limited means. These early plots tended to centre on the stations at Laindon and Pitsea. Advertisements appeared at strategic points around London, many of them stressing the hygienic nature of the countryside: 'Laindon - a lovely, lofty locality, loved by Londoners ... Rejuvenating rural residence', declared one alliteration-fixated leaflet.

The land-agents subsidised the rail fares of interested parties, and filled them with food and alcohol as soon as they stepped off the train. For this reason, the plots became known as 'champagne estates'. Many of the customers were poor East Londoners, who could not have afforded to buy a plot even if they had wished to. They just wanted a day out. Several of them did buy plots - under the influence - and never returned.

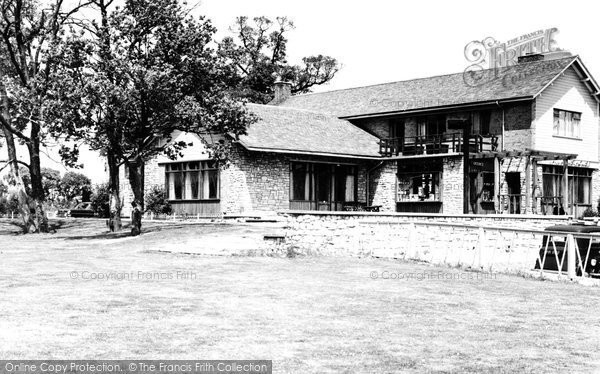

To stress the negative angle, however, is to do a disservice to the thousands of people who, over the next six decades, made the plotlands their home. The sales continued after the First World War, and the heyday of these rough-and-ready freeholdings was to occur in the 1920s and 30s. At first, the plotlands had simply been intended as weekend retreats for weary Londoners. Families would pitch a bell-tent on their patch of land. Gradually, however, they got the building instinct, and would arrive on Friday nights with a barrow-load of timber. Bizarre townships of shacks and bungalows began sprouting up like mushrooms. Often a railway carriage or a London bus would find its way onto a plot, and metamorphose into somebody's home. With the depression of the 1920s, these first-time builders were unable to afford luxuries such as bricks. They often resorted to corrugated iron and asbestos sheeting - anything that came to hand.

Nevertheless, people had begun to actually live in their constructions, and to commute to work. Basic though the accommodation was, it was often better than whatever London rookery they had left behind them. Maybe the advertisements were true: perhaps Pitsea was, indeed, 'picturesque' and Laindon 'lovely'. As the estates grew, so did the villages themselves: Laindon High Road became a continuous string of shops, as did the London Road at Vange and Pitsea. In terms of other amenities, however, progress was slow: mains water, for instance, was out of the question for most plotland dwellings. And, whilst some of the inhabitants clubbed together and solidified their roadways with duckboards, cinders, or (very occasionally) concrete, many roads were never more than grass tracks - wild in summer, abominable in winter.

During the Second World War, some of the unsold plots returned to agricultural purposes. The plotlanders, meanwhile, had become a permanent fixture, despite the flimsy nature of their homes. By the end of the 1940s, the population of Laindon-Pitsea was 25,000. The local authority, Billericay Urban District Council, was concerned about the lack of facilities in the area, but could simply not afford to give this big, sprawling settlement the makeover it so urgently needed.

Anyway, south-east England had more immediate problems. East London had suffered badly during the recent bombing raids. 20,000 people had lost their homes in East and West Ham alone. Something had to be done for them: new starts, and - if necessary - new towns. Sure enough, the New Towns Act was passed in 1946, and the search began for suitable locations. Stevenage, Crawley, Harlow ... all became names to conjure with. Billericay UDC must have thought it was Christmas: here was an opportunity to re-plan and rebuild on a major scale, and furthermore, the government would foot the bill. The Council were consequently unique in actually asking to be considered as the site for a New Town. The government liked the idea: after all, because of the plotlands, Laindon and Pitsea already had strong links with East London. The scheme was given official approval in May 1948, and the Minister for Town & Country Planning was sent, in due course, to explain the situation to the freeholders.

The Laindon Residents' Protection Association had sprung into life as soon as the news leaked out. For years, the freeholders had poured all their hopes, resources and time into what was now being described as a 'shanty town'. They were going to fight these proposals every step of the way. However, Basildon New Town's story is, as we know, a story of the little guy taking on the big corporation - and losing. Indeed, a vast number of residents welcomed the New Town with open arms. And who could blame them? There would be electric lighting, brick walls and flushing toilets.

Basildon Development Corporation was formed by the Department of the Environment in order to manage the New Town. They had a mountain to climb: the designated area was in roughly 30,000 ownerships. There were 1,300 acres of wasteland, of which half had no traceable owner. This was still causing headaches into the 1980s, as long-lost contracts turned up and descendants of would-be plotlanders tried to claim their inheritance. Some of the established freeholders did not go gently - barricading themselves inside their homes, or clambering onto their roofs with shotguns. 'Basildon was built on tears' became a familiar observation.

In any case, Basildon could not be built overnight. With an original target of 50,000 people living in 15 self-contained 'neighbourhoods', it would take time. An area between Laindon and Pitsea, not far from the old village of Basildon, had been selected as the centre of the New Town. But how could business and industry be attracted to an as-yet non-existent town? How could the freeholders be integrated with the incoming population?

The Development Corporation spent the next 37 years building houses. Several of the sites earmarked for development were saved by conservationists, much to their credit. It was not until 1986 that the Development Corporation was disbanded.

There had been mistakes, naturally. The wholesale demolition of almost all the area's ancient houses and farms now seems scandalous. There were human problems too, such as the 'Basildon blues' that afflicted some of the new settlers when they found themselves on half-built housing estates in the middle of nowhere. Where were the shops? The entertainments? Why did this New Town have no hospital or central railway station?

In many ways, Basildon's story is the story of the 20th century. All across the country, people were having changes thrust upon them by forces that were outside their control. They were understandably eager to claw back whatever they could, and make some tangible, attainable changes of their own. The Rt Hon Lewis Silkin knew that. When he stood and faced Laindon's freeholders in 1948, he used words like 'civilisation', 'knowledge' and 'community' - big things. Ideals. For decades, Basildon had been about small-scale, home-made things. But there was a wider world out there, and it was changing.

Outside it was already dark. Slowly, though, the second half of the 20th century was stirring into life.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Basildon History in Photos

More Basildon PhotosMore Basildon history

What you are reading here about Basildon are excerpts from our book Basildon Living Memories by Russell Thompson, just one of our Living Memories books.