Blackpool History

The history of Blackpool and specially selected photographs

For the past hundred years Blackpool has maintained its position as the premier seaside resort in England an still attracts millions of visitors each year. From its humble beginnings as a village of two hundred or so cottages, Blackpool has grown into a town with a resident population of over 150,000 people. Its greatest landmark is of course the Tower, an example of high Victorian engineering at its best, which rises to a height of 518ft and offers breathtaking views from the top.

The first reference to Blackpool that we have with any certainty appears in the Bispham Church register for 1602 recording the christening of Ellen Cowban, daughter of Thomas Cowban of blackpoole. And that is precisely what the place was; a black pool near the mouth of the Spen, its waters coloured by the peaty moss through which it flowed. The area was remote, marshy and windswept and was a part of Lancashire known as Agmunderness, whose main townships included Poulton, Rossall, Bispham, Lytham, Thornton and Inskip. When Ellen was alive most people along this part of the coast lived in single-storey cottages built with arched timbers (crooks), wattle and clay walls, and thatch made from rushes. One of the first houses of any substance to be built near the blackpool was Fox Hall.

It is said that around the year 1655 Edward Tyldesley, a member of a Catholic pro- Royalist family whose seat was at Myerscough Hall, near Garstang, built Fox Hall as a summer residence. An alternative theory is that given the Hall's remote location, it was in fact used as a base for pro-Royalist activities and that Charles II may well have been a regular visitor in the years before the Restoration. The Hall was close enough to the sea to allow the King a chance of escape should the need arise. Fox Hall was eventually abandoned by the Tyldesleys and after being used as a farm was converted into an inn; alas nothing remains of the original building.

In 1751 Blackpool as a town in its own right appears on a map, thanks to cartographer Emmanuel Bowen who recorded the place as Black Pool Town. There wasn't much to see, perhaps twenty or thirty cottages, but it was a start and the craze for sea-bathing was gaining momentum and by the end of the 1750s Black Pool Town consisted of cottages, the Gynn Inn, two hotels and Fox Hall.

It was in the 1780s that the area became a fashionable haunt for the sea-bathing set. In 1784 a summer season coach service operated from the Lower Swan Inn, Manchester, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The journey took about twelve hours, the inside fare being 14s and a meal stop was made at the Black Bull Inn, Preston.

Most of the inhabitants however continued to earn their living either labouring on the land, or fishing, or both. One story about the village goes back to the year 1799 when the Lancashire potato crop failed, and the corn harvest was so poor that prices rocketed. On top of this a freak storm broke along the coast, wrecking fishing boats, flooding inland and destroying or damaging many of the cottages. The people of Blackpool were now facing winter with little or no reserves of food and unable to meet the prices being demanded inland. But salvation comes in many forms. As the storm destroyed their homes and livelihoods, it also carried with it a merchantship, sails torn away and rudder smashed. Despite their own suffering men made their way down to the beach to try and help the crew of the stricken ship which by now was aground and in danger of breaking up. Then from nowhere a giant wave lifted the vessel bodily and brought it further up the beach, enabling the crew to be rescued before she broke up. Amid the debris were barrels, sacks and packages; it turned out that her cargo was mainly provisions, the bulk of it peas. The people of Blackpool survived the winter of 1799-1800 on a diet of peas, fish and cockles.

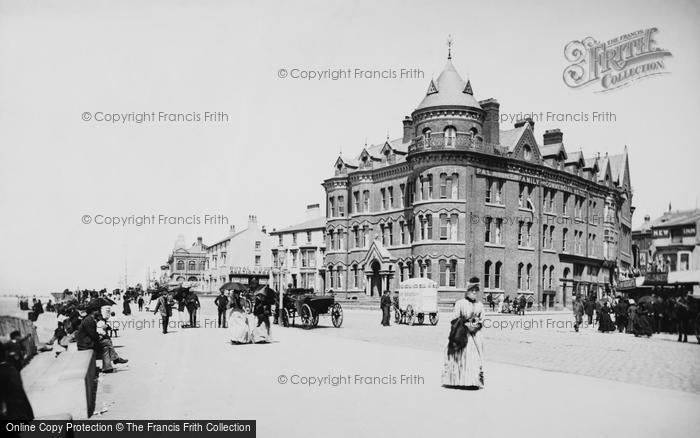

By the time the railway arrived in Blackpool in 1846 it was already a resort attracting several thousand visitors a year. Baileys Hotel, later the Metropole, had opened in 1776 and the first bathing machines had been imported by an enterprising inn keeper as early as 1730, though whether or not they were available for hire on Sundays so that the frail could be trundled to and from church is unknown; the two machines at Lytham were.

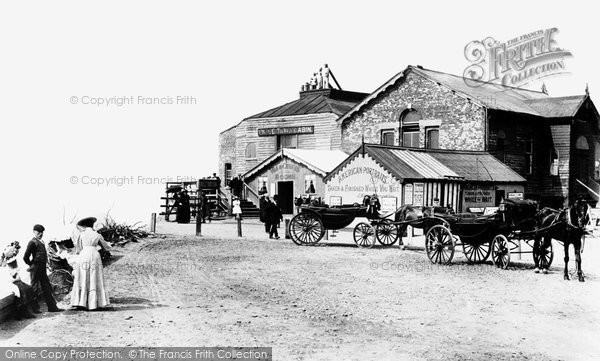

One of the earliest attractions was Uncle Tom's Cabin, which started out as little more than a wooden hut from which Thomas Parkinson sold sweetmeats and ginger beer during the summer season. Parkinson appears to have gone under the name Uncle Tom hence the Uncle Tom's Cabin. Eventually Parkinson sold out to a man named Taylor who went into partnership with another man in order to develop the business, even if they did turn down the chance to buy the field the cabin stood in and the one next to it for just £15. Fate now plays its hand. Some time after Taylor had taken over, a wooden bust of a negro, thought to be a ship's figurehead, was washed ashore. By coincidence one of the best selling books of the time was Uncle Tom's Cabin, so Taylor simply stuck the figurehead on the roof, added those of Eva and Topsy implying that the cabin was in fact named after the hero of the book.

During the 1830s Blackpool was still developing along genteel lines, though it must be said that for several decades the tradition of Lancashire working people and their families visiting the town had already begun, albeit on a small scale. Many would make the journey by cart, some would even walk, just to spend a few hours away from the dust, grit, grime and monotony of mill and factory life. Some resorts simply didn't want the lower social orders at play; the Yorkshire spa Scarborough even issued a broadsheet stating that 'the watering place has no wish for a greater influx of vagrants and those who have no money to spend'. The Scarborough broadsheet was also an attack on the railways, the very mode of transport that would bring both it and the likes of Blackpool and Southport much of their wealth.

By the 1870s many Lancashire cotton workers were enjoying the luxury of three unpaid days holiday a year, which when tacked onto a weekend gave a handy five-day break. Another important development for Blackpool's holiday industry was the passing of the Bank Holidays Act in 1871. With specific days allocated for holidays the railways companies could schedule special excursion trains, knowing that they would be filled.

With the railway investment in Blackpool's infrastructure and attractions gathered momentum. The North Pier opened in 1863 and was followed by a second, the South Jetty in 1868. In 1879 electric lighting was introduced along the promenade and the first illuminated tramcars ran as early as 1897, inspired it is said by the Kaiser's birthday celebrations in Berlin.

While Scarborough, Southport and Morcambe continued to provide for the genteel classes, Blackpool was developing along more gregarious lines. When it was opened in 1878 the Winter Gardens was probably the town's last throw at catering for a sophisticated audience, it housed a library, reading room, art gallery and concert hall, but the writing was on the wall as early as Whit weekend 1879, when the Garden's principal attraction was a young lady being fired from a cannon. As the popularity of the Gardens grew so Uncle Tom's Cabin declined despite it too having its own dance orchestra. For Uncle Tom's the end would come in 1906; not the victim of financial circumstances, but to nature itself when cliff erosion caused a part of the buildings to collapse.

In September 1885 Blackpool opened the first fare-paying street tramway in the country to be equipped with electric cars. Initially the tramway was confined to the promenade where it ran over a two-mile single line with passing loops every three hundred yards. The trams were powered by what was known as the conduit system, a positive current being carried by copper conductors in a central channel between the tracks. The cars were fitted with a shoe which fitted into the conduit and made contact with the conductors thereby picking up the current. The cars were capable of speeds in excess of 15mph but were in fact restricted by an interfering Board of Trade to 8mph. Though successful the system had its drawbacks in that the conduit was prone to loss of current due to it filling with sea water or drifting sand. The Corporation took over the line in 1892 and converted it to overhead wire in 1898-99.

In 1894 Blackpool pulled off the seaside coupe of the century with the opening of the Tower. At 518ft high, the Tower was based on that in Paris, Blackpool has never been shy at borrowing good ideas from elsewhere. As the crowds flocked in to see this engineering masterpiece, other resorts announced their intentions to build their own towers, but only Morcambe and New Brighton ever got anywhere. The Tower was followed in 1899 with the opening of the Tower Ballroom, modelled on the Paris Opera House, and famed for its mighty Wurlitzer organ which would feature in countless BBC broadcasts and make organist Reginald Dixon a household name.

By the beginning of the 20th century Blackpool was the preferred holiday destination for the majority of Lancashire cotton workers, but it was also drawing in holiday-maker from as far a field as Scotland, the Midlands and the North East. During Wakes Week 1919 no less that 10,000 people from Nelson stayed in Blackpool, while just 1,000 headed off to Southport and around 500 went to the Isle of Man via Fleetwood. The town became adept at handling large influxes of people. On Bank Holiday Monday in August 1937 no less than 425 special trains ran to Blackpool and that over the bank holiday period the town is said to have had five million visitors. True or not ,we do know that on one day in July 1945 over 100,000 people came to the town by train.

The 1920 Dunlop Guide describes Blackpool as ' the most popular seaside resort in England: scene of the holiday revels of Manchester, Liverpool, and the industrial centres of Lancashire generally. Blackpool has gone into the "business" of catering for the million exactly as into a business, and it was the pioneer in the advertising of local attractions, having secured a local Act of Parliament authorising expenditure out of the rates for that purpose. It is a frankly democratic and by no means exclusive place, but the entertainments, of which there is an almost endless variety, are the very best of their kind. The theatres, concert halls, zoological gardens, dancing saloons or ballrooms, gardens, Eiffel Tower, and other ingenious attractions are maintained with the most lavish expenditure of money. The site of Blackpool, a little over a century ago, was a sandy waste, and the town is scarce half-a-century old.'

Blackpool continues to attract large numbers of visitors despite the competition from package holidays and last minute deals by travel agents. The Pleasure Gardens prides itself on its spectacular rides and seems to be locked in some kind of duel with Alton Towers to come up with the most hair raising. The trams continue to run and the Tower is still standing, other places would have almost certainly got rid of both of them in the so called name of progress. If you have never been to Blackpool don't knock it until you have tried it.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Blackpool History in Photos

More Blackpool PhotosMore Blackpool history

What you are reading here about Blackpool are excerpts from our book Blackpool Photographic Memories by Clive Hardy, just one of our Photographic Memories books.