Chelmsford History

The history of Chelmsford and specially selected photographs

Not everybody likes Chelmsford, it is true. When the young Charles Dickens stayed there in 1835, he found it “the dullest and most stupid spot on the face of the Earth”. His main complaint was that none of the shops sold Sunday papers.

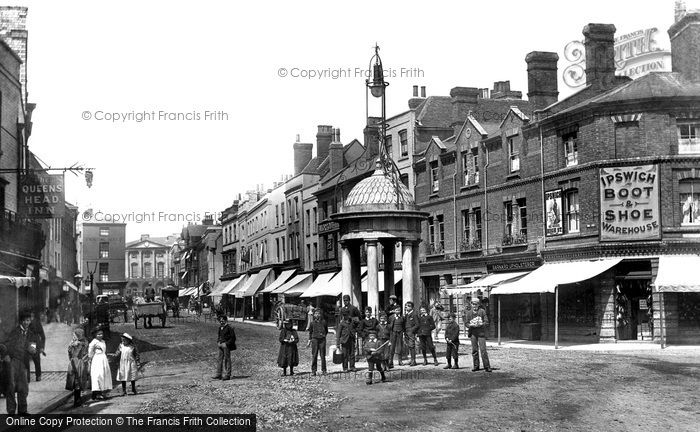

Chelmsfordians know different, though not all of them would care to admit it. It is a town that has been through many incarnations – market town, coaching town, industrial town, shopping town. For this reason, it frequently seems to be a town in transition.

The photographs in tThe Francis Frith Collection chart some of the changes Chelmsford has been through: horse-drawn vehicles vanishing in the face of bicycles, and then cars; the loss of old timber-framed shops; brave new civic buildings sprouting up in their place. Some fixtures seem to be ever-present – the Stone Bridge, for example – whilst elsewhere an inn becomes a church, and the church becomes a supermarket, all in the space of a few decades.

This is very much a feature of Chelmsford – and it’s a criticism that’s been constantly levelled against it: the failure to preserve its oldest and most interesting buildings. It’s true that much has been lost in recent years – Tindal Street, the Corn Exchange, the Friars – and that a lot of the newer architecture is, to put it mildly, lacking in appeal.

There’s a famous map of Chelmsford, drawn in 1591 by John Walker, in which every shop and tenement is faithfully depicted. It is a place of timbered gables, square courtyards, and chimneys like little red hammer-heads. There’s almost nothing here that’s recognisable, except the familiar shape of the High Street – wide at the top, and narrowing as it sweeps over the bridge into Moulsham; and the way the two rivers, the Can and the Chelmer, hold the town in their V-shaped clinch. So, even today, there is an older Chelmsford to be seen, it’s just that sometimes you have to use your imagination.

The earliest of the Frith photographs capture the town at a time of immense civic pride. It had become a borough in 1888. This was a very big deal: contemporary pictures show a sea of proud townspeople clamouring round the Corn Exchange on the day the Charter of Incorporation arrived from London. Interestingly enough, in 2012 Chelmsford applied for city status as part of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations. The application was successful, making Chelmsford Essex’s first city. It all comes round again, as they say.

For much of the 19th century, though, Chelmsford had been trying to pull itself up by the bootlaces: the upmarket development of New London Road, with its churches, infirmary and townhouses, had begun in 1839; four years later, the railway had steamed into town on an enormous red-brick viaduct. A Board of Health had been busy building a waterworks, opening a cemetery, and relocating the livestock market. Soon after Chelmsford’s incorporation, the town acquired its Recreation Ground: an expanse of fields and watermeadows were now laid-out with paths, flowerbeds, bridges and bowling-greens. Not far away, there were nonconformist churches and literary institutes appearing almost overnight. And in 1914, St Mary’s church achieved new status: a plucky little cathedral at the hub of England’s largest diocese.

However, if one is looking for Chelmsford’s architectural heyday, it’s usual to focus on the contributions of John Johnson, the County Surveyor in the late 1700s: his were the Shire Hall and the Stone Bridge – still two of Chelmsford’s most recognisable features. He also rebuilt the church after its roof fell in.

The Stone Bridge serves to remind us that Chelmsford’s origins were water-related. A Roman encampment had been established at the point where the London-Colchester road bridged the River Can. After a while, it developed into a small town called Caesaromagus – Caesar’s plain – the only town in Britain to bear Caesar’s name. It had shops, a temple and a bath-house. Everything had crumbled away, however, by the time the Saxons arrived – even the bridge. The new settlers avoided settling on the old site, preferring the higher ground near what’s now Rectory Lane. Nevertheless, there was one particular East Saxon – a man called Ceolmaer – who was in some way connected with a ford across the smaller of the two local rivers. At any rate, he gave his name to it: Ceolmaer’s ford – Chelmsford. It seems to have been a notorious crossing-point.

The Can was given a new bridge in 1100, and the through-traffic (which had been making a detour through Writtle for several centuries) was able to pass this way again. But there was still no town yet. It wasn’t until 1199 that Chelmsford was granted a market: this was to occur once a week, on Fridays. A triangular market-place appeared; the market-stalls became permanent shops, and a church was built to serve the new community. Chelmsford’s buildings met Moulsham’s at the bridge – it’s important to remember that this has always been a town of two halves.

The new settlement seemed to have a certain kudos. It made a good stop-over point for courtiers on royal business; its central position meant it was a convenient place for Essex’s assizes to be held; and at some point a friary was established in Moulsham. By the mid 13th century, Chelmsford was the county town.

And so it has remained, though it has always had its detractors. Chelmsford has simply learnt to weather the unfavourable write-ups in guide-books, the gentle lampooning by television comedians. It has suffered, certainly, from sharing a bed with Colchester – arguably the most historically interesting town in Britain.

Chelmsford isn’t a large place by any means, but then Essex, despite its high population, has never been a county of big towns. Nor is Chelmsford a glamorous place, because for the past hundred years, at least, its prime concerns have been industrial. We shouldn’t forget that Chelmsford was the first town in Britain to install electric streetlamps (albeit briefly), or that it was the cradle of radio-broadcasting. And, indeed, of ball-bearing manufacture. Let’s hear it for Crompton’s, Marconi’s, and Hoffman’s – Chelmsford’s “big three” engineering firms.

The Francis Frith Collection also contains pictures of some of Chelmsford’s outlying villages. Some of these outliers had already been engulfed by Chelmsford at the start of the 20th century, but it’s true to say that they still retain their own characteristics: Springfield with its mill and canal-basin; Great Baddow with its majestic church; Writtle with its duck-pond, village-green and timber-framed houses. Danbury and Little Baddow figure here, too: parishes of heathlands, woods, and surprising hills. On the opposite side of Chelmsford stands Pleshey, a curious village built inside the ramparts of a long-collapsed castle; and, completing the tour, Great and Little Waltham – hardy thoroughfare settlements that have become quiet backwaters since acquiring their bypasses.

History is a peculiar thing. Like nature, it can be extremely cruel: all too often, there’s a dog-eat-dogness about it – a quality that’s particularly pronounced in Chelmsford. The old gives way to the new. And it’s for this reason that Chelmsford, for better or for worse, is always “of its time”. Right now, it seems to be reinventing itself as a town of plazas, riverside walks, and shopping experiences. Good luck to it. Elsewhere, along Wharf Road, it’s just opened a new county record office that’s widely regarded as the best in the country. And, love it or loathe it, there’s the annual ‘V’ festival in Hylands Park. People are hearing of Chelmsford, who had never heard of it before.

Outside Loveday’s, the long-established jeweller’s at Baddow Road corner, there’s a sculpture. It was unveiled in 1999, and is called “Guardian Figures”. On one side there’s a Roman centurion, on the other side a Dominican friar. It’s good to remember the pioneers.

Chelmsford may not have sold Sunday papers in 1835, but it’s really got a lot going for it.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Chelmsford History in Photos

More Chelmsford PhotosMore Chelmsford history

What you are reading here about Chelmsford are excerpts from our book Chelmsford Photographic Memories by Russell Thompson, just one of our Photographic Memories books.