Doncaster History

The history of Doncaster and specially selected photographs

During the Roman period, a fort was built at Doncaster to guard a crossing place across the River Don. The name of the fort was first recorded as ‘Caer Daun’, but it was later known as ‘Danum’, which gave Doncaster the first part of its name; the ‘caster’ part derives from an Anglo-Saxon corruption of the Latin word ‘Castra’ for a military camp. The site of the Roman fort is believed to have been where the minster church of St George now stands. The present building, which was promoted to a minster in 2004, was constructed between 1854 and 1858 to a design by Sir George Gilbert Scott (and considered to be one of his finest works) to replace an earlier church which had been destroyed by fire some five years earlier. There is a local story that as the old church burned the vicar suddenly exclaimed: ‘Good gracious, and I have left my false teeth in the vestry!’

King Richard I granted Doncaster a town charter in 1194, and in 1248 a charter was granted for a market to be held in the town. Doncaster thrived and prospered during the Middle Ages, and by 1334 it was the wealthiest town in southern Yorkshire.

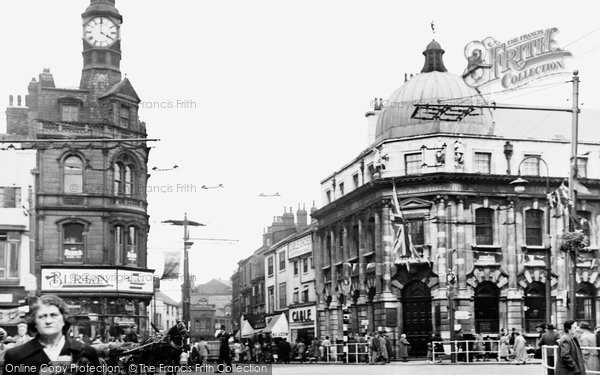

Many of the town’s street names have ‘gate’ in their names, such as Baxtergate. This derives from an old Scandinavian word for ‘street’ or ‘the way to’, and is a reminder of the time when much of Yorkshire was settled by people of Danish origin. In the Middle Ages, people plying the same craft or trade tended to live and work in the same part of town, and ‘Baxtergate’ originally meant ‘the bakers’ street’. The junction of Baxtergate, Frenchgate, St Sepulchre Gate and High Street is known as Clock Corner because of the huge clock on the tower that tops the building there. There has been a clock on the site since 1731 but the present Clock Corner building was erected in 1894. In recent years the clock has been mended and restored. It plays a Westminster chime on the hour and every quarter from 8am to 10pm. In addition, for the ten days running up until Christmas the clock plays the Christmas carol ‘Silent Night,’ and on New Year’s Eve it plays ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

Doncaster owes its transformation from an agricultural to an industrial centre to the coming of the railways in the 19th century, when the Great Northern Railway chose Doncaster for the site of its locomotive and carriage and wagon workshops. The Doncaster Plant was particularly famous for building LNER 2, 4, and 6 Class locomotives such as the Mallard, the holder of the world speed record for steam locomotives, and the Flying Scotsman, notably used on the London to Edinburgh service, both of which are now in the National Railway Museum in York.

In the early part of the 20th century Doncaster became one of the largest coal mining areas in the country, and the town was ringed with pit villages. However, the local coal mining industry declined in the 1980s as elsewhere around the country, as pits were closed and most of the mining jobs were lost. In its heyday, Doncaster’s coalfields helped to develop many other local industries, especially steel foundries, wire mills and glass production, many of which are still in business; Bridon (formerly British Ropes) is believed to be the largest wire rope manufacturing plant in Europe; and local firms such as Rockware Glass are still renowned high quality specialist glass manufacturers.

Doncaster’s electric street tramway opened on 2 June 1902; it operated fifteen open-top cars, each capable of carrying a total of 56 passengers. In 1928 Doncaster introduced trolleybuses. These gradually took over all the existing tram routes, and the tramway closed on 8 June 1935. The trolleybuses themselves were finally replaced by diesel and petrol buses in December 1963.

There have been horseracing meetings in Doncaster since 1600, but it was the St Leger of 1776 that put the town on the racing calendar. It was established by Lt Gen Anthony St Leger in 1776 and is the oldest classic race.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.