Ipswich History

The history of Ipswich and specially selected photographs

Many people tend to draw a comparison between Ipswich and Norwich as the major towns in their respective counties. If nothing else, an East Anglian derby match between Norwich City and Ipswich Town football clubs excites far more local passion than if either team were playing Manchester United! Although both towns are founded on ancient communities, Ipswich is more important than Norwich as a port - and indeed, it always has been. It is situated at the point where the freshwater River Gipping joins the head of the tidal Orwell Estuary, and even as far back as the 7th century Ipswich was not merely a trading port, it was the biggest in the country. Known then as Gippeswic, this Anglo-Saxon port survived many Viking raids. It very quickly established itself as a place of industry, producing a distinctive grey type of pottery which we know was widely distributed, both throughout East Anglia and beyond. It is very likely that the close proximity of the East Anglian royal palace at Rendlesham had a marked bearing on the fortunes of the town, as much trade in imported fine wines, furs and textiles passed through here, as well as the products of the local industry being sent from here to other ports along the coast.

By the time of the Conquest, Ipswich had its own mint, and by the beginning of the 13th century the town's status was confirmed with its first charter, awarded by King John. The middle ages saw the town prosper through the East Anglian wool trade, and by the 17th century, there was also a thriving ship-building industry using Suffolk oak, with shipyards lining the banks of the Orwell. Indeed, in 1614, Ipswich was quoted as having more shipwrights than any port in England. In Georgian times, the town suffered a commercial decline, but its prosperity was restored by the Industrial Revolution, evidenced by the large number of 19th century houses in the town. Engineering businesses like Ransomes established themselves, producing everything from railway equipment to agricultural machinery.

But at the end of the 18th century, the most pressing problem was with the docks, where large ships were unable to berth. The river was silting up, and even at high tide it was becoming impossible to get upstream. The solution, which took another forty years, was to construct the Wet Dock by isolating a bend in the river and diverting the river itself into a bypass channel known as the New Cut. With lock gates to control access to it, the Wet Dock provided the means for ships to be able to dock at any state of the tide - at the time, it was the largest such enclosed area of water in Europe. Further improvements were made to the dock, but by the end of the First World War, the port had expanded beyond the Wet Dock - the river had been dredged and quays built to accommodate large ships. Ships do still unload in the Wet Dock, but increasingly it is being taken over by yachts and pleasure boats, while the cargo vessels unload at the riverside quays - the oil and grain terminals on the east bank, and the container and roll-on roll-off berths on the west.

The railway arrived in Ipswich in 1846, and with that came further expansion and improvements to the town's prosperity. However, it was not until 1860 that a tunnel was cut through Stoke Hill, thus enabling the line to be continued to Bury St Edmunds and Norwich.

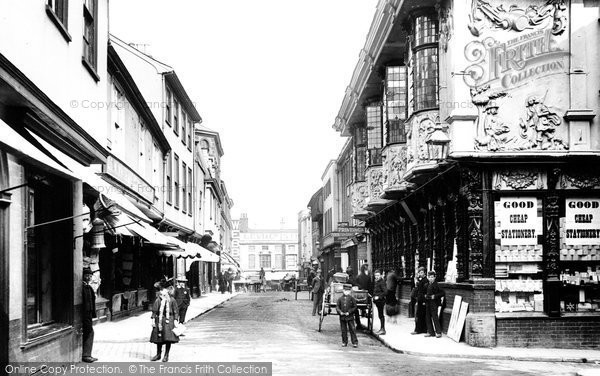

The basic street pattern of the town centre is still that of the medieval town, including a fine range of buildings dating from the 15th century onwards. Like Norwich, Ipswich was once surrounded by a wall, a legacy of which can be found in many of the street names, such as Westgate and Northgate. Cornhill, with its flamboyant mock Italian and Jacobean-style buildings, is on the original site of the market place of the town; it was also the place where several 'heretics' were burned at the stake. One block away is the Buttermarket, which contains the town's most famous building, the Ancient House. Also known as Sparrowe's House, this remarkable building is over five hundred years old; the walls of its upper floors, with their bay windows, overhang the lower part. Its interest lies in the elaborate moulded plasterwork designs on its outer walls - it is probably the best surviving example of pargetting in Britain. The panels below the first floor windows represent the continents of the known world at that time - Europe, Asia, Africa and America - along with the arms of Charles II (who, it is said, hid here after the Battle of Worcester) over the main doorway.

Just to the west is the Unitarian Meeting House, built about 1700. Inside, four great wooden pillars, said to be from ships' masts, form part of the structure, while the carved pulpit is quite probably the work of Grinling Gibbons. It is likely that this building was one of the first purpose-built non-conformist chapels, the Toleration Act having been passed only ten years previously. On the corner where St Nicholas Street is joined by Silent Street stands a magnificent group of Tudor houses with a carved corner post. Cardinal Wolsey is reputed to have been born in this area, and a plaque on one of the houses commemorates this. Nearby is Wolsey's Gate, the only surviving part of Cardinal Wolsey's ambitious plan to build a College of Cardinals. The building was started in 1527, and would have been quite extensive. But Wolsey fell from grace when he failed to support Henry VIII's wish to marry Anne Boleyn, and it was never completed. The brick gateway, with its barely discernible royal cipher, is all that remains.

Just a few years later, Christchurch Mansion was built on the site of the 12th century priory of the Holy Trinity. This Tudor country house is now a museum, and its adjoining art gallery houses a fine collection of paintings by Constable and Gainsborough. It is interesting to recall that this marvellous house almost became a housing estate in the late 19th century. The Cobbold brewing family bought the building and then presented it to the town, thus enabling us still to enjoy this monument to gracious living.

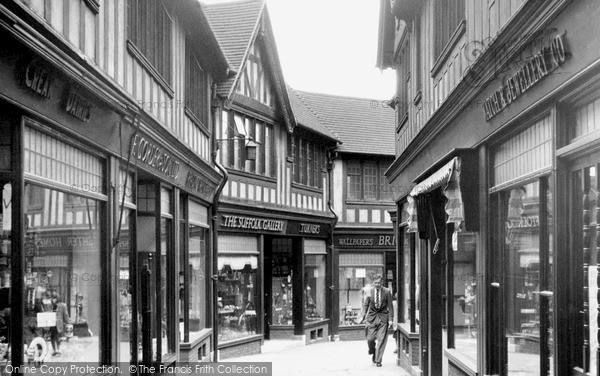

Tavern Street contains the Great White Horse Hotel, which, despite its Georgian facade, is a timber-framed building dating back to the 16th century. Famous visitors have included Dickens (who wrote about it in Pickwick Papers), George II in 1736, Louis XVIII of France in 1807, and Lord Nelson in 1800. Opposite the hotel stands a group of buildings which appear to be Tudor, but are in fact reproductions, built in the 1930s when such imitations were in vogue.

Today, despite the presence of the two major ports of Harwich and Felixstowe only ten miles away at the mouth of the Orwell, Ipswich remains an important industrial and commercial centre.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Ipswich History in Photos

More Ipswich PhotosMore Ipswich history

What you are reading here about Ipswich are excerpts from our book Ipswich Photographic Memories by Clive Tully, just one of our Photographic Memories books.