Plymouth History

The history of Plymouth and specially selected photographs

Despite the role it has played in many of Britain's great historic moments and periods, Plymouth is a city apart. Although only 200 miles from London - the same distance as, say, Manchester or Liverpool - its location on the south-west peninsula has given Plymouth an isolation, even today, that other cities lack. And it is not merely the distance that has isolated the city - its site is bounded on all sides by obstacles. To the north are the stern hills of Dartmoor, to the east the River Plym and to the west the Tamar. Early visitors to the peninsula on which the city would eventually grow would have to wait for the tide at the Ebb Ford, where Marsh Mills roundabout now stands, before they could cross the Plym and put their feet up at the Crabtree Inn, which over the centuries welcomed many a tired and mud-spattered traveller. Those coming from the west had two choices: to travel north to Gunnislake, the lowest bridge on the Tamar and some twenty miles up the river, and thence via Tavistock and Roborough Down, or to take the ferry that ran at Saltash across the strong tides of the Tamar. Even for land travellers, Plymouth was a place governed by the tides.

Plymouth grew from several small settlements, one of the earliest being Mountbatten, at the mouth of the Plym. The site of an Iron Age cemetery, Mountbatten is thought to have been a trading post from as early as 1,000 BC, and in Roman times exported cattle, hides and tin - the first indication of the maritime future of the area. Opposite Mountbatten the small fishing village of Sutton grew around the sheltered harbour of Sutton Pool; it eventually became a town when it was granted a market in 1254 by Henry III. By this time, ships loading tin from the rich port of Plympton had started to use Sutton too, and a lively trade was developing. Fish, hides, lead, wool and cloth were exported, while iron, fruit, wine, onions, garlic and wheat were landed.

1295 saw an event that was to point the wat for future development when Edward I assembled the fleet at Plymouth for the first time. The port occupies a crucial strategic position guarding the Western Approaches; it was this factor that was to cement Plymouth's importance, and was probably a consideration when Henry VI granted the borough charter in 1439.

If Plymouth's maritime status brought prosperity, it also meant that the port was often in the front line, especially when Spain was involved. Francis Drake, knighted by Elizabeth I for his circumnavigation of the globe in 1577-80, sailed from Plymouth to 'singe the King of Spain's beard' at Cadiz in 1587 and returned to face his sternest test in 1588 - the Spanish Armada. His apparent bravado on insisting that he finish his game of bowls at Plymouth before engaging the mightly Spanish fleet was dictated by the mundane fact that his ships could not sail until the tide had turned, but what is not in doubt is that his courage and seamanship helped carry the day for the English fleet. Drake did not, as is commonly believed, command the fleet - that responsibility fell to Lord Howard.

Years of fighting Catholic Spain probably explain the streak of puritanism that Plymouth showed for the next hundred years. The city welcomed the nonconformist Pilgrim Fathers when the Mayflower put in for repairs and provisions before sailing for the New World in 1620, and during the Civil War of the 17th century it took Cromwell's side. Plymouth was isolated, as Barnstaple, Bideford and Exeter were all captured by the Royalists and Royalist ships blockaded the Sound.

The nine thousand Parliamentarian troops garrisoned at Plymouth held out under siege for two years, winning a famous victory in December 1643 in the battle whcih raged around Tothill and Freedom Park. Prince Maurice Road and Mount Gould are named after the Royalist and Parliamentarian commanders. Plymouth was eventually relieved in March 1645 when Cromwell and Fairfax met in the city.

Upon the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Charles II decided that Plymouth's defences needed strenghthening and commissioned the building of the Citadel. One of the finest and largest Restoration forts in the country, it boasted upon completion 152 guns, some of which faced the city as a reminder to Plymothians of their true place in the order of things.

Secretary of the Navy Samuel Pepys, now known for his diaries but also effectively the founder of the Royal Navy as we know it, visited Plymouth with Charles II in 1676 to inspect sites for a new Royal Dockyard. Turnchapel, at the mouth of the Plym, was considered, but eventually the prize was given to the Tamar. The Tamar's disadvantages - strong tides, a narrow and winding entrance and often contrary winds - also acted in its favour as they gave the river natural defences from attack; work started on what is now Devonport's South Yard in 1691. Another sign of the port's growing stature was the building in 1696 of Winstanley's 120-foot lighthouse on the Eddystone Rocks fourteen miles off the Hoe, the first in a series of four that would culminate in the current lighthouse built by Douglas in 1878.

Investment notwithstanding, Plymouth struggled for the fist half of the 18th century. Fishing still thrived, particularly for pilchards, and trade carried on, but Plymouth has never figured near the top of the table as a commercial port because of its isolation and the lack of nearby markets. Bristol and Liverpool made fortunes from the slave trade, and London's demand for commodities ensured that her docks were always busy, but Plymouth slumbered on, depressed and waiting for a turn in the tides of history.

War, by now a recurring theme in the fortunes of the city, provided the catalyst. From 1756 a succession of conflicts - the Seven Years' War, the American War of Independence and the Napoleonic Wars - caused an upturn in Plymouth's fortunes. Her isolation was eased in 1758 with the completion of the Great West Road, although it still took twelve hours to reach Exeter. The Royal Naval Hospital in Stonehouse was built in 1758-62, the dockyard bustled, and in 1812 the famous Scots engineer John Rennie began the construction of the Breakwater. A massive undertaking which was not completed until 1841, the Breakwater was a crucial development. Generations of mariners such as Grenville, Howard and Raleigh had complained that the relatively narrow entrances to the Plym and Tamar were dangerous in foul weather; mariners would often run before the storm to anchor in the sheltered waters of Tor Bay. Now, all a gale-battered ship had to do was slip in through the eastern or western entrances and move into the lee of the Breakwater, with plenty of sea-room and calm water in which to anchor.

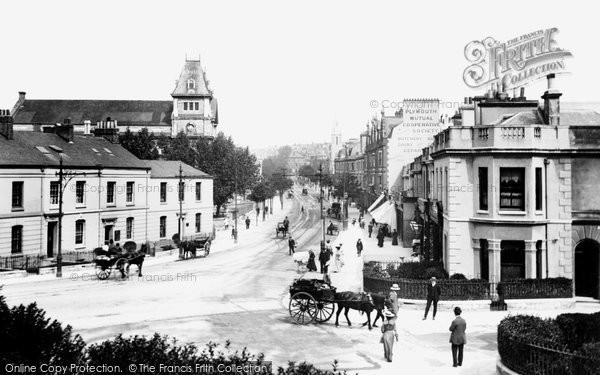

The railway arrived in 1848-49, and at last Plymouth had a rapid connection with the rest of the country. Isambard Kingdom Brunel's magnificent railway bridge over the Tamar, completed shortly before the great man's death in 1859, had more than a mere practical significance - it was a symbol of Plymouth moving with the times.

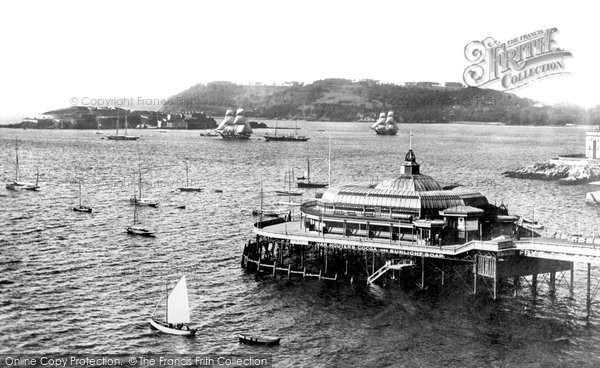

John Foulston's Theatre Royal provided entertainment for those who could afford it, while those of lesser means could promenade on the pier or take the air on the Hoe. In the 1920s and 1930s, transatlantic liners anchored in the Sound, discharging passengers such as Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Rudolph Valentino to catch their train to London from the Millbay Docks.

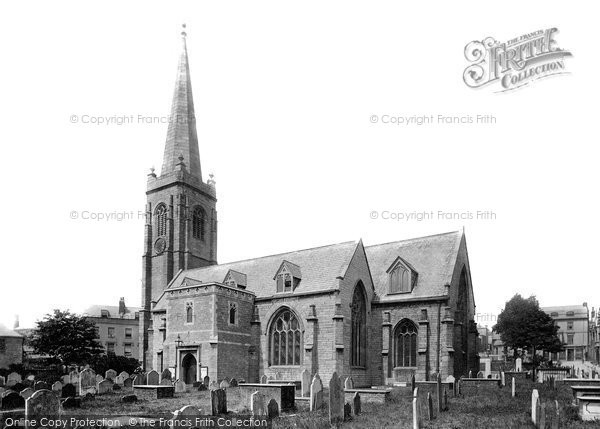

Plymouth prospered, but the clouds of war were gathering again; during the Second World War the city lived through its darkest hours. As a major naval port, Plymouth was high on the Luftwaffe's target list. A series of intense air raids in 1941 left the city devastated; much of the city centre was reduced to rubble, and fine buildings such as the Theatre Royal, the Royal Hotel, the Post Office and the Municipal Buildings were lost for ever. But the people of Plymouth were unbowed. Thousands left the city each night for the foothills of Dartmoor and safety from the bombs, and returned to work the next day. The shell of St Andrew's Church was planted with flowers and hundreds came to worship in the 'Garden Church', while on hot summer evenings, thousands would come from the ruined city to dance on the Hoe with digitaries like Lady Nancy Astor MP and cock a defiant snook at Nazism.

Once the war was over, thoughts turned to reconstruction. It is a loal joke that what Hitler started, the town planners finished: it is true that the new, geometric street plan of the city centre is a little uninspiring, but St Andrew's still stands, and the broad sweep of Armada Way leads one seawards to the heights of the Hoe.

Stand on the Promenade on a clear day and turn through 360 degrees, and all around are reminders of Plymouth's past. To the north are the blue hills of Dartmoor, source of the tin that caused the port to come into existence. West is the entrance to the Tamar, home to the frigates, aircraft carriers and submarines which slip in and out of port in all weathers, even in peacetime. Merchantmen anchor in the lee of the Breakwater, ready to discharge their cargoes of petrol and fertiliser on the wharves of the Plym, and trawlers set sail from a largely unchanged Barbican for the fishing grounds. And on the horizon, the Eddystone light winks unceasingly, a beacon for mariners heading for one of Britain's great ports.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Plymouth History in Photos

More Plymouth PhotosMore Plymouth history

What you are reading here about Plymouth are excerpts from our book Around Plymouth Photographic Memories by Martin Dunning, just one of our Photographic Memories books.