Wolverhampton History

The history of Wolverhampton and specially selected photographs

Heated arguments rage about whether Wolverhampton is in or out of the Black Country. In fact the city lies squarely across the north-west border of the region and was historically in Staffordshire. Residents in the leafy western suburbs some years ago were surprised to see new signs on the main roads welcoming them to the Black Country. The inhabitants of the industrial eastern suburbs on the other hand are amazed that anyone could imagine that they were not part of the Black Country.

There are two Wolverhamptons. One matches the prevailing national image of a dull, uninteresting, unattractive industrial city with nothing worthy of distinction other than Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club. The other Wolverhampton is the one that Wulfrunians know: a city with a distinct and thriving shopping centre, with miles of quiet green suburbs and distinct local village or town centres such as Penn, Tettenhall, Bilston and Wednesfield. Wulfrunians have all the advantages of living in the West Midland conurbation with the bonus of never being more than two or three miles from unspoiled open countryside.

The local accent is distinct from that of neighbours such as Sedgley, Dudley, Tipton and Birmingham, most of all Birmingham. The Wolverhampton accent is sadly not highly regarded nationally and is lumped together with all West Midland accents as Brummie. Nothing annoys Wolverhampton folk more than to be labelled Brummies by their accent. In fact they would not live in Birmingham if they had the choice, and they pity those who do.

The list of famous people coming from Wolverhampton is not a long one, consisting largely of modern sportsmen and women and popular singers. The most successful pop acts are Slade and Beverley Knight. However Dame Maggie Teyte, the early 20th-century international soprano was also born in Wolverhampton. The town attained some notoriety in the 1960s when the local MP Enoch Powell made his famous speech on immigration predicting dire consequences if it was not controlled.

Wolverhampton was a town, and is now a city, that began as an Anglo-Saxon settlement well before the Domesday survey of 1086. Some of the place names in the area are Celtic: Penn (hill, top), Trysull Brook, now the Smestow Brook, (from ‘troi’, the Celtic word for turn, twist), but no evidence of a pre-Anglo-Saxon settlement at Wolverhampton has been found. Let us at this point dispose of the myth, recently become more widespread, that the Mercian king Wulfhere founded the town in the 7th century. There is no evidence for this apart from a fanciful derivation of the name of the town. The traditional foundation date is AD985, when Aethelred granted land at Heantune to Lady Wulfruna, but this suggests there already was a settlement. She endowed the church in 994.

After the Conquest of 1066 the Norman barons were given control of all England by the new king, William I, who gave to Samson of Bayeux the lands of Hantone (High town), together with the slaves, villagers and other inhabitants, who would have carried on their lives much as before, not caring which particular lord they served.

In medieval times the town was a centre of the wool trade, hence the woolsack in its coat of arms.

Wolverhampton has featured remarkably little in national upheavals over its thousand years. After the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, some of the conspirators were chased to nearby Holbeach House at Himley. The town was very active in the 1640s during the English Civil War. In 1642 Prince Rupert passed through the town stopping at a house in Victoria Street. Important local families supported the king so Wolverhampton was a Royalist town if anything, but it fell without resistance to the Parliamentarians in 1643. King Charles I came through in 1645 and stayed overnight. The fleeing King Charles II stayed at Moseley Old Hall and hid in the oak tree at Boscobel, and the restoration of the monarchy was declared on High Green (Queen Square) in 1660, but that was all the excitement there was going to be.

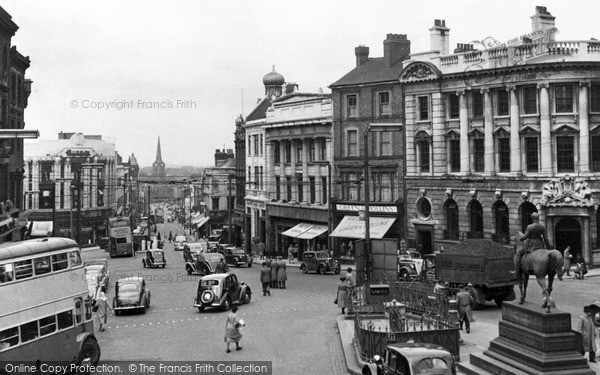

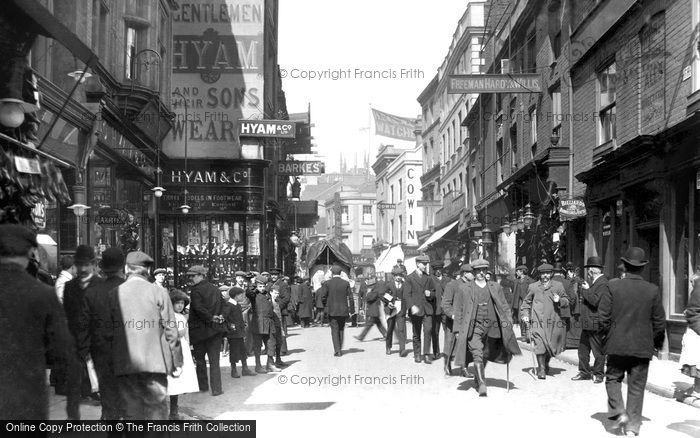

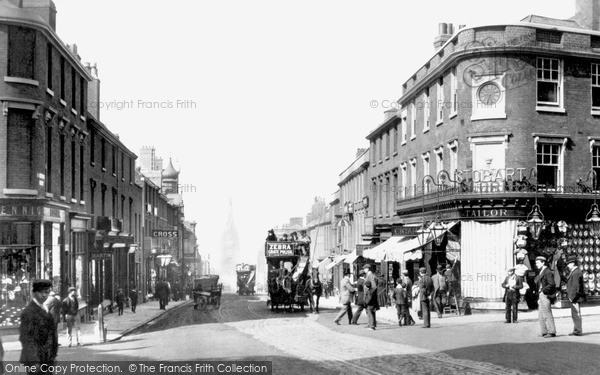

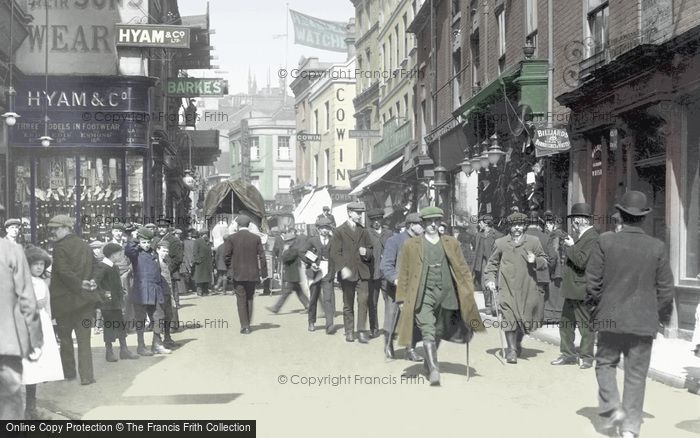

Little of medieval, Tudor and 17th-century Wolverhampton survives today. We can still see the churches in the city centre and at Penn, Bushbury and Tettenhall, a half-timbered remnant in Victoria Street, another in Exchange Street and a few scattered farm buildings, for example at Northicote and Merridale. The basic street plan however survives remarkably well. In the city centre the modern streets generally overlie their medieval counterparts. Former places such as High Green (Queen Square), Cock Street (Victoria Street), Horse Fair (Wulfruna Street), Goat or Tup Street (North Street) and Barn Street (Salop Street) have all been renamed, but Dudley Street, Lichfield Street and Stafford Street still bear their old names. Old photographs and engravings show some of the buildings that have been lost. There was a fine Tudor hall in Queen Square, demolished in 1841. Lichfield Street was lined with half-timbered buildings until all were cleared away in the 1880s to widen the street and build the Art Gallery. The building on the corner where Barclays Bank now stands was a particularly fine example of 16th-century architecture that lasted until the 1870s. The town centre was largely rebuilt in the 19th century and much Victorian architecture remains in several main streets, but Dudley Street and Victoria Street, the two main shopping areas, consist of more modern buildings with very few exceptions. The photographs in this book of Queen Square, the area round the Art Gallery and down Lichfield Street to the Britannia Hotel are still very recognizable today. Most of the buildings look cleaner and in better repair now than they did 50 years ago. Other pictures will be familiar to older inhabitants but strange to the young. The area around Molineux and down North Street for example has completely changed since the 1970s. Although much enlarged by many new houses, Tettenhall and Penn are still highly sought-after residential districts, while Bilston and Wednesfield have benefited from bypasses, but retain much of their character.

The industrial revolution that began in Shropshire came to Wolverhampton, a quiet little market town, and completely transformed it. The population grew from 12,000 in 1801, to 50,000 by 1851, 100,000 by 1921 and nearly 250,000 today, with the inclusion of Bilston, Tettenhall and Wednesfield. The population has been greater than this since the war, but the replacement of many of the streets of small terraced houses by modern houses at a lower density has meant that fewer people live inside the city boundaries. The 19th century saw the rapid building of much needed housing, which for the ordinary worker was largely cheap and crowded, although many better houses were built for the middle classes. Wolverhampton has had its borders drawn very tightly around the existing built-up areas, so much expansion has had to take place just outside the borough boundaries in Staffordshire, in Perton and Wombourne.

Wolverhampton’s industries in the 19th century ranged from japanned ware, lock manufacture, tin ware, steel products, chemical works, brewing, iron foundries and brassware, to hundreds of small manufacturing businesses making everything the consumer needed. Wolverhampton was ideally placed to benefit from the proximity of raw materials and good transport connections by road and canal, and later rail. A hundred years ago the town was described by some as being without trees and greenery, a real part of the Black Country, and by others as being elevated, airy and surrounded by lovely countryside. This conflict of images of the city is still the same today. Industrial development continued through the 20th century as Wolverhampton added other industries such as vehicle and engine manufacture to its industrial base.

After the demolition of whole districts in the 1950s, 60s and 70s for redevelopment and to construct the ring road, local planners realised almost too late that they still had much of interest and attractiveness worth preserving in the city. A process of preservation and regeneration began which has included restoration work on Lindy Lou and the upper floor of the building next door in Victoria Street, shops in Lichfield Passage and Worcester Street, terraces of 18th-century buildings in King Street, George Street and Snow Hill, and St Peter’s Gardens. There are other examples around the city of similar efforts to rescue its architectural heritage. Parallel with this has been the drive to put residential accommodation back in the city centre. In common with many places, by the 1990s the centre of Wolverhampton had become a place in which no-one would choose to live. In the last ten years upper floors of shops have been renovated to become apartments, and prestige city centre homes have appeared in Market Square, by the canal in Horseley Field and elsewhere.

Wolverhampton is unfortunate in lacking an outer ring road. The roads into the city are generally wide and do their job well but through traffic going from north to south and east to west has to go almost into the centre to get round the city, take an enormous detour, or suffer the clogged M6. The M54 and Black Country Route have helped a little, as has the new toll motorway, but it is a pity that no-one had the foresight in the 1930s to plan a route around the perimeter of the town. To build such a route would nowadays be very expensive and disruptive of residential areas and the proposed construction of a route further out into the countryside, such as the currently abandoned western bypass, has been understandably bitterly fought against by people who moved out there for some peace and quiet.

Until recently scant regard was paid to preserving the heritage of the buildings all around us, especially in a city like Wolverhampton, which was not regarded as being of great architectural interest. Fortunately we now live in an age when old buildings are valued for giving us continuity with our past, and a good quality of urban environment is recognised as an asset in our daily lives. We all feel better for living in an attractive and well looked after place. It is also the case that prosperity attracts prosperity and the downward economic slide of a town is worsened by obvious signs of urban blight. Whatever our political views might be, it is unarguable that Wolverhampton today is a cleaner, brighter and better cared-for place than it has been for a long time.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Wolverhampton History in Photos

More Wolverhampton PhotosMore Wolverhampton history

What you are reading here about Wolverhampton are excerpts from our book Wolverhampton Photographic Memories by David Clare, just one of our Photographic Memories books.