Gloucester History

The history of Gloucester and specially selected photographs

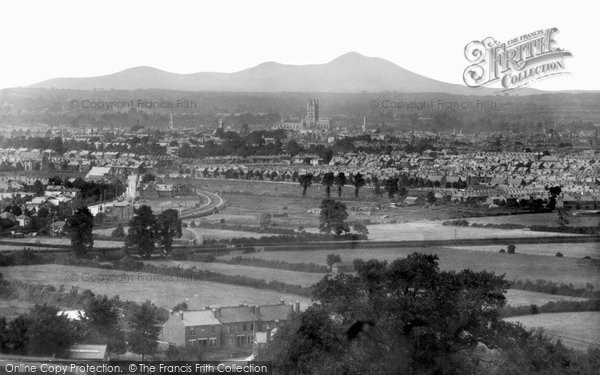

The City of Gloucester stands on the site of an old Roman fortress, and around the year AD 43, the Christian faith came literally floating up the Severn river with the advancing legions from Rome. To educate the people that lived in this old part of west Britain? They certainly did. And here they built a Roman station - Glevum, or Gloucester as we know it today. The reason for this location was that the site was the first point on the Severn river where a bridge could easily be built; the same reasoning that made London such a major centre of residence and business at the time. By AD 97, or thereabouts, it is documented that Gloucester was a self-governing city, what we would call a colony or Colonia today. This status was bestowed on the city by the Roman occupiers of the time, and in particular Emperor Nerva. The famous Roman Second Legion, which he led, retired its soldiers and families to the settlement of Glevum from its base in Caerleon (Isca Silurum). Because of this the area flourished and became the commercial centre of the Severn valley. And Gloucester enjoyed the same, if not similar, rights as the city of Rome itself. The corners of Brunswick Road and Parliament Street reflect the old defensive land lines of the original fortress, where gateways to the city’s core could be found. Roman reference to the area was not made until 577, and more likely 582. At this time, just north of Bath at Deorham (now Dyrham), Caewlin led his army on Candidianus, a Roman Briton, and two Welsh Princes, Fernvael and Cynvael, all of whom represented Britain in Roman terms. All three were killed and Caewlin ensured the whole area, encompassing Glevum, was passed back in to English hands. Organised Christian institutions in Glevum perished.

After this Gloucester formed part of an area called Hwicce and King Aethelred of Mercia laid the foundations of a monastery in 681. Periods of instability followed with Welsh invasions raking the city, fires through negligence caused damage, and the civil war between Beornwulf (King of Mercia) and Coelwulf, his successor, tearing the fabric out of the area and destroying the foundations laid down by the Romans 600 years before. Thereafter the Danes encamped about the city and plundered everything in their wake. But Alfred the Great moved them on at the battle of Ethandune in 878, after which he passed the city to his daughter, Aethelflaed, and her husband Aethelred.

It is interesting that archaeology, an ongoing process of course, is still teaching us about the city and its origins dating back thousands of years. We do know that many celebrities of the day found their way to Gloucester, and many historic dates are centred on the city. In 900 Aethelflaed founded a free chapel royal in the city to keep the remains of St Oswald, and in 1085 William ordered the doomsday survey from the palace buildings, located in the area known today as Kingsholm. Edward the Confessor resided in the city, as did Alfred the Great. And Aethelstan, Emperor of all Britain died in the city in 940. Rufus ‘The Red King’ penned his poetic lines there after illness that he would never again rule England a sick man, and Henry I made his son Robert an Earl of Gloucester.

During the mid-11th century Ealdred, the Bishop of Worcester, set about resetting the monastery buildings in Gloucester. The appointed abbot was a man called Wulfstan, who was succeeded in 1072 by Serlo, the founder of the present cathedral of Gloucester. In fact the history of the cathedral begins with Serlo, who energetically raised funds and placed buildings and construction within the confines of the cathedral that were not only grand but sumptuous.

Gloucester city has many features but, of course, the main one is its cathedral. It will surprise many people that it has only been a cathedral since 1540. Prior to that date it was a church described as the Benedictine abbey of St Peter, its cathedral status would have to wait. The history of the building itself will always be in doubt. Abbot Serlo is given the benefit of the doubt that it was he who built the cathedral from its foundations. An earlier Bishop, Ealdred, had furnished Glevum with a church north of the Roman wall of the city; had Serlo stripped these down totally, or did he, as some suspect, move the structure to form a part of the new church buildings? The answer may lie with the crypt, which boasts work from two different periods and is the cause of further speculation. Could it be that Serlo built the main body of the church, and Bishop Ealdred built the crypt? Or that Serlo added weight to the crypt building as a necessity of time and ruin? It is open to conjecture, which makes the structure that more interesting and appealing. Whatever the case, by the year 1100 the church was dedicated, broadly with the same ground plan as it has today. In 1122 the wooden roof of the central tower burst into flames during a congregation, and much of the tower was lost. In 1170 the western tower collapsed, and at this point the reader may well begin to query the stability of the entire building.

An architect would point to inferior work - the structure does not have the solidity of Durham or Winchester. However, Helias of Hereford, a man who was called a ‘building enthusiast’ of the time, presided over the rebuilding of the central tower in a very English style, his talent for interior design assisted by Abbot Henry Foliot. In 1239 it was rededicated by Walter Cantelupe, Bishop of Worcester.

Fire again damaged the abbey in 1300, the damage taking seven years to correct, and Abbot John Thokey took on the challenge of building the new dormitory, and the whole of the south aisle of the nave - which was ready for collapse. The windows and vaulting of the aisle remain as a dedication to his hard work. If there was ever a question over structure, there is none over its restoration. The cathedral boasts daring masonry work, and ingenious redesign. The men and women who dared to work in dangerous conditions saved the nave from falling down like a deck of cards or, in the words of Professor Willis, “Like a capsized ship”. Building would then go on for over two more centuries as the cathedral took on a very different feel.

Gloucester is the birthplace of the Perpendicular style. Thokey and his successors all contributed to the focus of the Perpendicular nature of the church and Abbot’s Wigmore, Staunton and Horton can all take the plaudits for continuing Thokey’s vision. Perpendicular roof vaulting is believed to have been commenced by Wigmore and his master builders in about 1350, and the work is unparalleled. The Norman style was tampered with and the cathedral acquired characteristics not seen anywhere else in England. Walter Froucester, a renowned figure in the history of the building, completed the cloisters which many would say have not been matched - anywhere! It is a perfect structure. The cathedral now had a Norman nave, Gothic vaulting, a Perpendicular choir and transepts in a Romanesque outer shell. Morwent would be involved in the South Porch in years to come and Thomas Seabroke planned the cathedral’s greatest feature, the central tower. Abbot’s Hanley and Farley finished the building off with the Lady chapel to leave the cathedral as we know it today. Not a mismatch of styles and ideas, but a transformation over centuries of building, of decoration and refurbishment that leave us with a view of one of the most unique and special buildings England has to offer.

In 1378 a Parliament met in Gloucester which formed the constitutional heritage of the whole of the country. And Henry VIII visited the city with Anne Boleyn as his queen, and again with Jane Seymour, after Anne‘s decapitation as a traitor. From then on every King and Queen would visit Gloucester, and Elizabeth I granted Gloucester the privilege of a seaport.

The great Civil War saw Gloucester as the only supporter of Parliament whose army of the time had been obliterated. The city stood alone. In fact Lord Essex gathered an army from London and, defying all, marched to save the city. Colonel Edward Massey, the city’s governor, was by this time ready to serve anyone, be it King or Parliament, as Prince Rupert amassed an army of 6,000 cavalry troops on the east of the city, while to the west stood 8,000 infantry. It seemed the city would fall if Lord Essex could not make it in time. Only some 2,000 men held firm within the city, testament to the strong-willed people of the area that are portrayed in this book. King Charles I called for Gloucester’s surrender and was defied. Lord Essex rallied 14,000 men and marched on foot from London to Gloucester. It took 13 days - some say 18. The people inside the city were awoken on 5 September 1643 by a blaze of cannon fire from Prestbury Hill, Cheltenham, as Lord Essex announced the arrival of his army. The royalists streamed away from the city walls and the London army marched in to the city’s confines. Having held off the Royalist forces for weeks, all Massey had left was three barrels of gunpowder. Massey was indeed a mercenary soldier, a soldier of fortune for whom self-preservation was the main cause. But he was, and always will be, known as the defender of Gloucester.

The meeting point of Gloucester’s four main streets - Westgate, Eastgate, Northgate and Southgate Streets, which constitute the arms of a cross drawn through the heart of the city - provides Gloucester’s focal point. Today, the main shopping areas of the city spring from these roads. The meeting of these four roads is known as The Cross, which is dominated by St Michael’s Tower. This structure dates back to the 14th century, and the roads lead away from here to the old city gates of Gloucester. Prior to this an old stone cross was in this position, however because of its size and obstruction of the highway it was removed in, according to the journals of the day referring to “The Antient Cross”, the week of 5 November 5th 1751. Following an Act of Parliament in 1749, the streets of Gloucester were to be enlarged, and a number of buildings taken down.

The port of Gloucester is adjacent to the Bearland courts and city police station, and has enjoyed a huge resurgence in fortune in recent years. It is the furthest inland port in Great Britain, and is connected to the Severn estuary by the Gloucester and Berkeley canal. During the expansion of the railways in the mid-19th century, masses of produce found its way via these docks. Prominent was corn, grain and timber, but it would not have been out of place to see convict ships setting off for every corner of the globe as impressive quays and warehouses sprang up to cater for the new trade. It was Queen Elizabeth I who granted the city a charter in 1580, which gave it the title of a seaport, and for centuries thereafter Gloucester was a major sea artery for trade. In 1654 the very first HMS Gloucester was launched, and in 1982 the tenth vessel so-named was launched. In 1780 over 600 ships were logged as mooring at the dockside.

It is hard to picture the scene of the docks in the 19th century with the area packed tightly with sailing vessels of all shapes and sizes, with little regard for rules and regulations. Companies such as Haine & Corry, established coal and builders merchants, and Price, Walker & Co (Romans timber yard), did business here for many years. Later on, wartime submarines would venture in to the Severn estuary from these docks via the canal, to fight against German aggressors. Today the docks are well-preserved with small restaurants, shops and drinking clubs for all ages. The City Council is housed in the North Warehouse, and then there is the waterways museum - a focal point for visitors, with a whole day’s-worth of browsing heritage to consume. Many of the warehouses remain, vast buildings that have also enjoyed redecoration, and at every turn there is a reminder of what has gone before. The antiques centre on the dockside, on the site of the old lock warehouse, houses 110 dealers on five floors covering 20,000 sq feet. Gloucester docks are indeed a visit in themselves, rising to the right leaving the city towards the Bristol Road, and encompassing new and old buildings around the striking watery vein running through the middle - the reason why the whole area is what it is. So dedicated to the past are these docks, that TV film makers often visit the area, ‘The Onedin Line’ was filmed here over a number of years. The Glorious Glosters, a regiment of great tradition, has its history charted at the military museum too.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Gloucester History in Photos

More Gloucester PhotosMore Gloucester history

What you are reading here about Gloucester are excerpts from our book Gloucester Photographic Memories by Keith Haynes, just one of our Photographic Memories books.