Portsmouth History

The history of Portsmouth and specially selected photographs

The sea, geography and war, each, between them, have determined the history and development of Portsmouth, and still determine the city’s fortunes today. The great natural harbour and, to a lesser extent, neighbouring Langstone Harbour, provide safe anchorages, and the deep water channel which hugs the coast has brought ships safely to these shores over many centuries. Portsmouth’s geographical position on the south coast, within easy striking distance of French shores, placed first the area and later, the town itself, firmly on a natural line for sea-borne traffic connecting this country with the continent from the Bronze Age. Finally, and most importantly, Portsmouth has supplied this country with the ‘sinews of war’ since the late 12th century. A royal dockyard and garrison town since the early Tudor period, Portsmouth flourished when this country was at war and languished in peacetime. It was John Leland, the 16th century traveller and antiquarian, who visited Portsmouth c1540 and noted in his journal that ‘the toun of Portesmouth is bare and litle occupied in time of pece’. The sea, geography and war have shaped the history of this city.

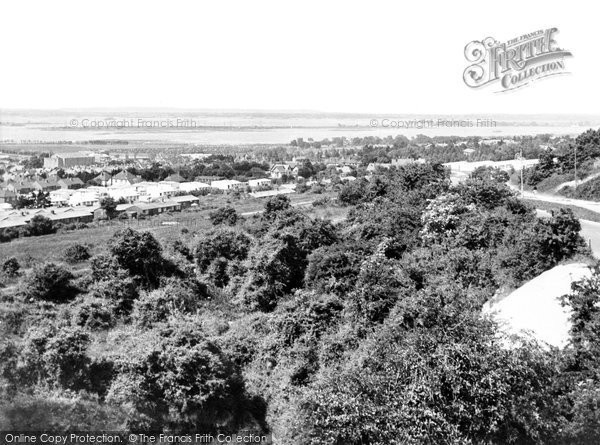

The Early Years: The original township was established in the late 12th century, in the southwest corner of a low-lying, marshy island, Portsea Island, which is flanked on the west by Portsmouth Harbour and on the east by Langstone Harbour. Portsea Island’s southern shores are lapped by the Solent and sheltered by the Isle of Wight. Its northern shores are separated from the mainland by Portscreek, a narrow channel which links the two harbours. The fertile coastal strip to the north of the creek rises dramatically to the top of Portsdown, the three-hundred-foot-high chalk outlier of the South Downs which runs east to west from the outskirts of Havant to the boundaries of Fareham, and effectively separates Portsmouth from greater Hampshire.

The new township at the harbour mouth was founded by a wealthy French merchant and landowner called Jean de Gisors c1180. He had interests in the Portsmouth area already. His grandfather, Thibaud de Gisors, had been granted the manor of Titchfield by William the Conqueror’s son and successor as King William Rufus, for services which he, Thibaud, had rendered the English side in Normandy in the struggles between the English and the French in the early 12th century.

Jean de Gisors was probably drawn to the site at the harbour mouth by its potential for developing cross-channel trading links. The community at the top of the harbour was ceasing to be an attractive option for development as the northern reaches were now silting up significantly.

Many new towns were established in the 12th and 13th centuries, including at least eleven in Hampshire. The ‘new’ Portsmouth conforms very much to the general pattern. It was built on the initiative of the lord of the manor on a well-established grid pattern of streets and lanes. A marketplace was designated and settlers encouraged to move into the town on favourable terms in the hope of long-term financial benefit accruing to the lord of the manor and his family from developing trade. In fact, it is more than likely that Portsmouth’s fair and market, which were granted formally in the first Royal Charter of 1194, had been established some years before by Jean de Gisors.

There were other advantages to this new site. The harbour, of course, provided a safe anchorage, but a settlement just inside the harbour mouth and near the deep-water channel and open sea could take larger ships than the site at the top of the harbour. The shingle spit at the harbour entrance also provided additional protection for ships within its lee. The Camber, as it has been called from that day to this, provided an obvious site for a quayside - the Town Quay, as it became subsequently known.

Jean de Gisors and his family did not benefit long from the revenues coming in from his new development. He forfeited all his English property, including Portsmouth, to the Crown in 1194 - for backing the king’s brother, Prince John, when the king, Richard I, was a prisoner of the German Emperor, Henry VI. After King Richard returned to England in March 1194, John’s rebellion against his brother collapsed, his partisans and known supporters fled - and their lands were confiscated. Exchequer records note that ‘Portsmouth is an escheat of the lord king and is worth with its belongings £20’. Land which was confiscated by the Crown was usually sold on promptly to whoever was prepared to pay the best price. The king’s financial needs were pressing. He had still to pay the balance owing on his ransom and he had to find the resources to assemble a fleet and put an army into the field to wrest back Normandy from the French king. Much of the land of John’s supporters was therefore sold on, but the king did not dispose of Portsmouth. As stated in the city’s first royal charter, granted by the king to local residents on 2 May 1194, the king ‘retained’ the town in his own hands. The reasons were simple - sea, geography and war.

Richard I, like Jean de Gisors before him, could see the strategic importance of this township beside the sea. It lay on an administrative axis stretching from the old Norman ducal capital of Rouen to Caen, a town which had been growing in importance during the 12th century and where Richard’s father, Henry II, had established the Norman Exchequer in 1172 in the great fortress built by William the Conqueror. From Caen, it was an easy journey across the Channel to Portsmouth and from there to the old Saxon capital of Winchester, where the English treasury was still located. Portsmouth would be a useful link in this chain of communication. Unlike in Southampton, there was no powerful merchant class in Portsmouth likely to frustrate the king and his designs. During Richard’s reign, many loads of treasure were shipped across the Channel through Portsmouth. The harbour was also a useful rendezvous and haven for ships transporting troops, and had plenty of space ashore to assemble men and supplies for military campaigns. The town prospered in the remaining years of Richard’s reign.

He put the town’s facilities to good use immediately. Men and ships were summoned to Portsmouth, where he joined them on 25 April, anxious to put to sea at once. The weather was not promising, though. When he tried to sail on 2 May, in the teeth of a gale, he was forced to put back into port. The weather did not improve sufficiently for him to attempt the crossing again for another ten days. It was during his brief stay in the town at this time that Richard granted Portsmouth its first royal charter. Portsmouth was now a royal borough, independent of county administration. The town was entitled to hold a fair annually for fifteen days and a weekly market. It was also granted exemption from a wide range of different tolls and exactions, and given criminal jurisdiction within its boundaries.

All sides could be pleased with the deal. Portsmouth now joined the ranks of those other towns in England, many much larger, such as Norwich, Ipswich, Lincoln and Gloucester, who also acquired similar privileges at this time. The king brought firmly under royal control an important new strategic position on the south coast. There was no risk now of a powerful merchant group emerging which might threaten the military and naval role planned for Portsmouth. Work began immediately on the construction of appropriate accommodation for king and court. Described variously as the King’s House or the king’s houses, the new buildings occupied a site at the top of Penny Street belonging today to Portsmouth Grammar School, but known as Kingshall Green for much of its history. In due course, a great hall with cellars, a chapel and domestic buildings was constructed on the site, surrounded by walls and a ditch.

Records show that large sums of money were spent at this time on the king’s houses, their defence and other works in the town, including, possibly, ship repair facilities. A separate set of accounts had to be established in the Exchequer to record expenditure. They itemise not only the large sums of money passing through the town for transport to Normandy, and the costs of the building works, but also such domestic expenditure as the 14 tonnels of wine unloaded and placed in the cellars of the King’s House and what it cost to take the king’s hawks to Normandy with ‘engines of war’. These were probably wooden structures capable of hurling missiles at the enemy, or even wooden towers on wheels for siege work. The accounts also record the considerable numbers of fighting men moved through Portsmouth at this time in ships requisitioned specifically for such purposes.

As for the ship repair facilities, these may well have been part and parcel of the king’s plans for making Portsmouth the base for his galleys on the English side of the Channel. At the same time as work began in Portsmouth, similar developments were taking place on the Seine, at Les Andelys, midway between Le Havre and Paris, beneath Richard’s great castle of Chateau Gaillard. Les Andelys would be the base for the galleys in Normandy. Richard’s successor, his brother, John, is usually the one credited with establishing Portsmouth dockyard in the early 13th century, but it is looking increasingly likely that Richard should have the credit for this initiative some 30 years previously.

Little survives above ground today of the late 12th-century town other than the medieval grid pattern of streets and the chancel and transepts of St Thomas’s Church, now Portsmouth Cathedral. Portsmouth Cathedral is the oldest surviving building in Portsmouth. The original chancel and transepts are part of the chapel built on the instructions of Jean de Gisors in the 1180s. They are impressive in scale. Money was clearly not stinted on the project. Nikolaus Pevsner, in the ‘Hampshire’ volume of ‘The Buildings of England’ series, describes St Thomas’s as having ‘more of the character of a miniature cathedral or monastic church’. Excavations undertaken between 1968 and 1971 in Oyster Street - on the site of the medieval quayside - did uncover something of the original settlement, however. There was evidence of permanent occupation from the late 12th century, clearly identified from a combination of stratigraphy and structural remains - beam slots or gulleys, post holes, hearths and depressions - and ceramic and other finds. There is evidence of at least two permanent buildings in the earliest occupation levels, and a complex of buildings, a well and water cistern in the 13th- and 14th- century levels when the town was beginning to grow in size.

A system of local government was in place by the early 13th century. There are references to town officials and a borough court in both the Southwick Cartularies and in Exchequer records. References to a common seal occur from the 1240s and by the end of the century there is definitely a mayor and a common seal in use to authenticate official documents.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Portsmouth History in Photos

More Portsmouth PhotosMore Portsmouth history

What you are reading here about Portsmouth are excerpts from our book Portsmouth - A History & Celebration by Sarah Quail, just one of our A History & Celebration books.