Norwich History

The history of Norwich and specially selected photographs

Norwich is a fine city, despite the ravages of Second World War bombing and wholesale ‘improvement’. Like all modern cities, it is surrounded by suburbs in which can be found the remnants of older villages. It has a population of about 170,000. In the early nineteenth century, when almost all the city was still within the medieval walls it had a population of about 35,000.

A Roman road once crossed the river Wensum at Caistor-by-Norwich where, it is thought, there was a government weaving works producing cloth for Roman army uniforms. Clearly wool production has a very long history in East Anglia. The first real settlements in what is now Norwich were Anglo-Saxon. These grew sufficiently to become a fortified burgh which by about 920 AD had its own mint, and had been given the name Norwic. It continued to grow and by 1066 could sustain about 40 churches and was the third largest port on the east coast of England after London and York.

After the Norman Conquest more than 100 houses were cleared for the castle and more for a new market-place and the cathedral close area. The cathedral, or rather the bishop and the priory, arrived in 1094 when the see was transferred from Thetford.

The city spread rapidly and from the mid thirteenth until the mid fourteenth centuries, stone city walls were built with no less than 11 fortified gateways. The walls, stretches of which survive today were about 2.5 miles long. They protected only three sides of the large medieval city. The fourth side was protected by a mile of the bank of the River Wensum.

The medieval city grew up on the wool trade and it was one of England’s wealthiest cities with a population of about 15,000 by 1340. Indeed until 1700 it was the second largest and wealthiest city after London.

The southern areas of the city, such as Ber Street and Rouen Road were bombed during the Second World war and subsequently and redeveloped with what can tactfully be termed mixed success; the huge number of surviving churches, as well as the cathedral and the intricate street pattern, give a quite remarkable feel of a medieval city.

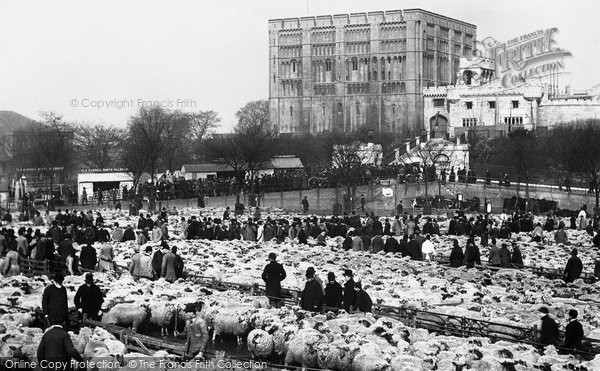

Norwich’s Norman castle-keep is all that survives of the medieval castle buildings and is a remarkable structure. Built around 1100, on a low hill, it replaced an earlier Norman timber castle. At over 70 ft high it dominates many parts of the town, in fact considerably more so than the Cathedral which is more prominent beyond the city. The castle appears an austere cube in distant views, but from closer to, the tier after tier of blind arches can be seen. All this work is new stone put up when the castle was refaced in the 1830s. This is an accurate copy of the Norman work but in alien Bath stone, instead of the original pale Caen limestone from Normandy, which was brought by barges up the Wensum.

Attached to the castle is the old prison, built in the 1820s on a radial plan, at the time the very latest in prison planning. The castle had actually been a gaol, many centuries before, and certainly by the early thirteenth century. In 1887 the city bought the castle and converted the gaol into an art gallery and museum. The gallery has many fine works by the Norwich School of topographical artists, including John Sell Cotman and John Crome.

In the first half of the fourteenth century, the city’s timber defensive palisade, on an earthen bank behind a ditch was wholly replaced in stone. Some idea of the scale of the enterprise can be given by raw statistics: 40 towers, 11 gateways, more than 2½ miles of 20 ft high wall, the wall had arcades supporting a wall walk behind the battlements and was fronted by ditches 20 ft deep and 60 ft across. Even then the walls did not surround the whole city, for the mile or so of the Wensum river frontage in the east has no walling. The best place to see surviving stretches of the wall of this great medieval enterprise is in Chapelfield Gardens. A number of towers survive. These include the pair of boom towers that raised a chain across the Rover Wensum to prevent enemy shipping penetrating the city and, more splendidly, the isolated brick faced Cow Tower of 1390 which defends a curve of the Wensum where there is no wall.

For 900 years, the city of Norwich has had its bishopric, transferred from Thetford in 1094. The first bishop of Norwich, Herbert de Losinga, had bought the bishop of Thetford’s mitre in 1091, along with the Abbacy of Winchester, from William Rufus who was quite happy to sell ecclesiastical appointments. Thetford was too near the mighty Abbey of Bury St Edmunds with whom the bishops of Thetford had been in near continuous dispute. Norwich had the undoubted advantage of being a long way from Bury and had long been a thriving town. De Losing arrived and, in the high-handed way of Norman aristocrats, promptly cleared a substantial part of the town to make his cathedral precinct. The foundation stone for Herbert’s great cathedral was laid in 1096. The east arm, the chancel, was ready for dedication in September 1101. De Losinga died in 1119 and never saw his great project completed, indeed it had reached only the east part of the nave. It was completed by his successor in 1145.

Remarkably little has happened since, compared with the history of many other English cathedrals. The building is still essentially Norman and only the great late fifteenth century spire has materially changed distant views. It soars to 315 ft, the second highest spire in England after Salisbury. Its predecessor had been blown through the choir roof in a great gale in 1362, which also resulted, in the building of the superb spacious clerestory of the choir.

The greatest and, remarkably, most successful and harmonious change to the Norman cathedral, was the addition of stone vaults throughout, after a disastrous fire in 1463. The nave was done first followed by the transepts and the choir by 1500. It is astonishing that these intricate rib patterns and their glorious carved bosses complement the Norman work of 300 years before, but they undoubtedly do. The cathedral is one of the finest in England and one of the most complete Norman ones. Herbert de Losinga and his successor, Eborard de Montgomery, would still feel at home.

Outside the cathedral there is a considerable acreage of green space within the precinct walls. The tranquil precincts are focused on Upper and Lower Closes. They run down to the River Wensum and contain a considerable number of historic houses as well as substantial remains of the pre-Reformation priory. Much of its medieval precinct wall survives, together with the watergate to the Wensum at Pull’s Ferry and two medieval gatehouses into the town: truly a splendid legacy.

The other medieval glory of the city, apart from the cathedral of course, is its parish churches. An astonishing number survive, many with non-ecclesiastical uses now, but, even so, few cities can rival this profusion. At its medieval peak the city had 56 parish churches within the walls. There are still 31, although there were 36 before the Second World War. Five were destroyed by bombs. Such dominance, combined with the old street patterns give a remarkably medieval flavour to Norwich, despite an overwhelming majority of post-medieval secular buildings.

In the past the River Wensum was the city’s most active trade route. South-east of the city it joined the River Yare which reaches the North Seat at Great Yarmouth. The wealth of Norwich depended on the river down which flowed its worsted and cloth trade. Indeed, so great was the trade that during the Middle Ages Norwich became the third most important east-coast port and until about 1700 was the second largest city in England.

Turnpike roads of the late 18th century, and after 1844 the railway, reduced the importance of the river to the newly-industrialised city, which by now had textile, shoe-making, leather-working, brewing and metal industries. But until the First World War the river was humming with activity, mostly sailing barges carrying bulky goods, raw materials and local trade. Leisure boating took over in the 1920s and a yacht station was established by Riverside Road. This is still immensely popular and for much of the year, Broads cruisers and boats tie up at the numerous moorings so that holiday-makers can visit the city.

Historically of course, the river was also a valued part of the city defences. The city grew in the river’s loop so, in effect, the river was a wide wet moat along its east side. The defences included the boom towers south of Carrow Bridge, whose chain boom could be raised to close the river, preventing access upstream and the Cow Tower at the bend opposite St James’ Hill. The cathedral precincts’ watergate, known as Pull’s Ferry after an Elizabethan ferryman, originally guarded the entrance to a canal that ran west into the Close; barges brought building stone from Normandy up the canal for the cathedral and priory.

Now the river bank has a splendid riverside walk from east of Whitefriars Bridge, through parks around Cow Tower and Pull’s Ferry, to beyond the boom towers. The city has several municipal parks: these range from Chapelfield Gardens, laid out in 1877 by the city Corporation on an infilled reservoir, to the extraordinary Eaton Park of the 1920s in the suburbs. The most untamed public open space taken over by the city Corporation is the 180 acres of the famous Mousehold Heath, which was bought in the 1880s. The heath had originally been an area of about 6000 acres. Once Anglo-Saxon 'wildwood', most of it was enclosed about 1800.

The city’s expansion in the 20th and 21st centuries has absorbed a number of villages, including Heigham and Old Lakeham. In the process it has acquired an outer an inner ring road, the University of East Anglia, and a population of more than 180,000. Despite all this, the city retains its qualities and its historic core: it is a city to be savoured and visited and re-visited.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Norwich History in Photos

More Norwich PhotosMore Norwich history

What you are reading here about Norwich are excerpts from our book Norwich Photographic Memories by Martin Andrew, just one of our Photographic Memories books.