Blackburn History

The history of Blackburn and specially selected photographs

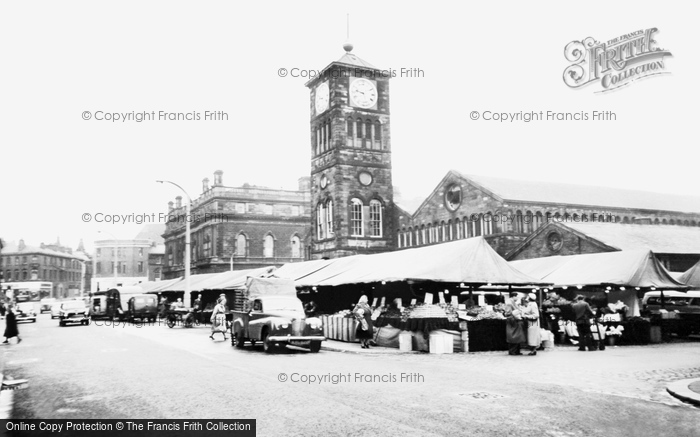

Celia Fiennes toured England at the end of the 17th century. She did not visit Blackburn. Thirty years later Daniel Defoe toured the country. He visited Bolton, Bury and Preston, and viewed Pendle from afar, but he did not come to Blackburn either. At this time Blackburn was the market town for north-east Lancashire, and had a population of a little over 5,000.

In 1933 J B Priestley made his 'English Journey', and he did visit Blackburn. In the 200 years since Defoe’s time, remarkable things had happened to the town. Handloom weaving as an adjunct to small-scale farming had been practised in the area for centuries, and quite extensively since the 18th century. With the invention of the power loom, the warehouses, which had been used to store the cloth pieces brought in by the handloom weavers, were converted into mills. Power looms were installed, and the formerly independent handloom weavers became employees. Their remote cottages had to be given up, and new homes, long rows of terraced houses, were built near the mills.

There was plenty of coal to be had fairly locally, and the damp climate suited the spinning and weaving of cotton fibres; and so the cotton industry boomed in Blackburn. The population had soared to a peak of 133,000 by 1911. At the time of Priestley's visit, however, the industry was in decline. It was a world-wide slump, but Blackburn, having relied heavily on just one industry, was hit particularly badly. Priestley described Blackburn as 'a sad-looking town', but added:

'The streets are not filled with men dismally loafing about. You do not see abandoned shops, which look as if they are closed for ever, down every street. Everything that was there before the slump, except the businesses themselves, is struggling on. In nearly every instance, the whole town is there, just as it was, but not in the condition it was. Its life is suffering from a deep internal injury’.

Blackburn stands on the river of the same name. It may be that the name means simply ‘black stream’, although in the Domesday Book it is written ‘Blacheborne’ and may be a reference to bleaching. If poor communications was the reason for its lack of visits by itinerant chroniclers of the English scene, then the industrialisation of Blackburn soon remedied the situation. The Leeds to Liverpool Canal reached Blackburn from the east in 1810 and from the west in 1816. The Turnpike Trust built Whalley New Road in 1820 and Preston New Road in 1825. The railway to Preston opened in 1846, to Accrington in 1848, to Burnley and Colne in 1850, and to Chorley and Wigan in 1869.

And along these lines of communication came those vital raw materials, coal and cotton, and perhaps the most significant raw material of all: human labour. The proliferation of mills sucked people in like a fire sucks in oxygen. They came from the rural areas nearby, from rural areas further afield, from Scotland and from Ireland. It was their labour which made Blackburn prosperous.

By 1836, in his ‘History of the County Palatine of Lancaster’, Edward Baines was able to describe the town thus: 'In the early stages of the cotton business, the inhabitants in general were indigent and scantily provided; (and this is still the case, so far as the hand-loom weavers are concerned;) but decisive proofs of wealth now appear in this place on every hand: handsome new erections are continually rising up, public institutions for the improvement of the mind and the extension of human happiness are rapidly increasing; and this place, at one time proverbial for its rudeness and want of civilisation, may now fairly rank, in point of opulence and intelligence, with many of the principal towns in the kingdom’.

The slump observed by J B Priestley was a temporary, if significant, setback. It was recognised that the former laissez-faire approach to the cotton industry could not be maintained, and that a more organised approach was needed. An act of parliament to control the industry was proposed, but World War Two intervened, and the demand for military clothing and equipment revived the industry.

After the war demand for cotton goods remained strong; the main problem was shortage of labour. Many employees had left to do war-work, and did not return. The solution was found by recruiting people from India, Pakistan and from among the displaced Asian population of East Africa

The fortunes of the cotton industry in Blackburn can be gauged by the number of looms in operation. The high point was reached in 1917, with 94,000 looms. By 1937 there were 35,000. After the war there was a slight increase, but from 1956 onwards there was a steady decline; by 1976 there were only 2,100. To all intents and purposes, the cotton industry and the 20th century came to an end together. By 1999 there were just 100 looms running in the town.

Again, communications have come to the town's rescue. The construction of the M65 in the mid 1990s linked Blackburn to the motorway network, bringing Manchester Airport to within a 40-minute drive and Liverpool Docks to within 90 minutes. Paper, chemicals, rubber and plastic industries are now all represented in the borough, and the town presents as busy and as prosperous a face as ever it did in its prime as a cotton town.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Blackburn History in Photos

More Blackburn PhotosMore Blackburn history

What you are reading here about Blackburn are excerpts from our book Blackburn Town and City Memories by Alan Duckworth, just one of our Town & City Memories books.