Bath History

The history of Bath and specially selected photographs

'Oh, who can ever be tired of Bath?' Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

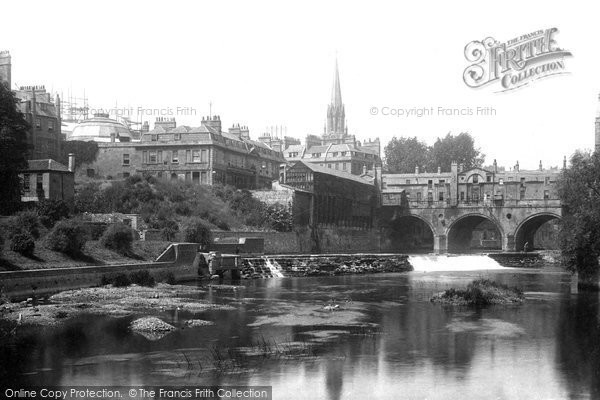

Bath is rightly designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is perhaps the most remarkably architecturally unified town in England, a quite outstanding example of Georgian town planning and even more so the vision of a father and son, John Wood the Elder and John Wood the Younger, a vision carried on by inspired architects like Thomas Baldwin in the later eighteenth century and even respected by the late Victorian architect, John Brydon. Who can forget the stunning architectural impact of the vast Royal Crescent or the sinuously curving Lansdown Crescent? From about 1720 to the 1820s an unique and mercifully complete Georgian city both overlaid the medieval city and expanded to the north, east and to a lesser extent the south of this town situated on a bend of the River Avon, thirteen miles east of the second city of the country, Bristol.

The Woods' extraordinary and dynamic vision built it, but its success as a spa town owed as much to the 'King' of Bath, Richard 'Beau' Nash who presided over its social success for nigh on half a century until his death in 1761. He 'by the force of Genius .. erected the City of BATH into a Province of Pleasure, and became by universal Consent its Legislator, and Ruler' and the city was 'able to vie with any city in Europe, in the politeness of its amusements, and the elegance of its accommodations'. Queen Anne had taken the waters in 1702 and this regal endorsement set the city on its way. However it is easy walking through the Georgian streets, squares, circuses and crescents to forget that the city had already had a long and illustrious history and we will look at that before returning to the eighteenth century.

The city's origins go back well before the Roman conquest of Britain in the first century AD. It appears that the springs were sacred to the Celtic Goddess, Sul. It is not surprising as these hot springs on the site of the city issuing forth over a quarter of a million gallons each and every day must have appeared a marvel of nature. The ancients clearly took a view that is still held today that if the waters tasted awful (and they do) they must be curative! When the Roman conquerors arrived after the invasion of 43 AD they rapidly conquered south and east England and constructed a military road from Lincoln to Axminster, completed by 47 AD, as a temporary frontier beyond which they soon advanced as far north as Scotland. This road still exists and is known as by the Anglo-Saxon name of the Fosse Way. The Roman military engineers brought it from Cirencester in the Cotswolds to cross the Avon at Bath before heading south-west towards Devon.

Presumably the Romans heard about the mineral waters and the shrine to Sul. Being great assimilators of native deities they rapidly took over the cult's springs and turned Sul into their own goddess, Minerva. Bath or rather Aquae Sulis, the 'waters of Sul' very rapidly became noted throughout Britannia and Gaul (modern day France) and thousands of the ill flocked here for cures for rheumatic and similar diseases. The Romans built a very impressive collection of bath houses and pools buildings, over three hundred feet long by one hundred and fifty wide. There was an oval, a circular and a square bath but the largest and a rectangular one was only rediscovered in 1880. Lead-lined it had steps into it from the sides and was surrounded by colonnades. Later it was stone vaulted over. The bases of the piers remain and the bath itself of course, fed by hot springs at a constant 50 degrees Celsius. John Brydon in 1897 constructed an appropriately Roman building around the newly discovered bath, open to the sky.

There was also an important temple dedicated to Sul-Minerva and fragments of this have come to light, but by far the most important were the remnants of its main pediment found in 1790 during building works for Thomas Baldwin's Pump Room. It is of the highest, indeed metropolitan quality and depicts the snake-haired and bearded Gorgon's head on the shield of Minerva which is supported by two winged Victories which I suppose must have been confused for angels when first found.

After the Roman legions left around 410 AD the town's fortunes declined and the baths fell into ruin. In 577 AD the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Bath, along with the old Roman towns of Gloucester and Cirencester fell to the Saxons, Cuthwine and Ceawlin, after a mighty battle at nearby Dyrham, killing in the process no less than three British kings. In 603 AD St Augustine passed through and by 676 AD the monastery established in the city received its first royal endowments of land. The Anglo-Saxon period was one of relative obscurity for the decaying town, although King Edgar was crowned king here at a great assembly in May 973 AD and in 1013 Swein Forkbeard, King of Denmark, accepted the fealty of the west of England at Bath. In the eleventh century the fortunes of the town revived and the abbey, now a Benedictine monastery, became one of the most important in England. After the Norman Conquest it became the seat of a bishopric in 1088 and a large Norman church was built. The present Abbey church was built on the site of the Norman nave only and is obviously much smaller than its great Norman predecessor, fragments of which remain incorporated in the east end. Bishop King commissioned the leading court architects of the day, Robert and William Vertue, to design the new church and it rose slowly from 1499 onwards, a magnificent Perpendicualr Gothic building with a fine central tower. A victim of the dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, work stuttered and stopped and the nave was only roofed (in timber rather than stone) in the early seventeenth century. The present stone vaults over the nave are nineteenth century.

The medieval town was a prosperous one, being in the centre of a wool and cloth producing area with a river to carry exports to Bristol. Indeed it was still important in 1700 when the town began its new life as a centre of fashionable health and leisure pursuits. Unfortunately very little of the medieval town survives, apart of course from some of its street plan. The Abbey is by far the biggest medieval artefact: of the rest there is only the much altered fifteenth century church of St Mary Magdalen and a bit of the town wall. There is physically little of the Tudors and Stuarts up to the Restoration of Charles II either.

The waters, however, had been taken from the fifteenth century on and the King's Bath was the focus, mostly of immersion but also a certain amount of drinking of the water (not from the bath itself, I should add). The 1597 spring or well top of the bath was replicated a century ago as its centrepiece and there is a famous print of men and women enjoying themselves in the King's Bath together: shocking behaviour to Beau Nash, the Arbiter of Elegance.

However, it is to the eighteenth century we must return. The city was in effect rebuilt, replanned and greatly expanded to accommodate the fashionable visitors who soon flocked to the city to take the waters, to gamble, attend assemblies and generally enjoy themselves for the Bath 'season'. Huge numbers of houses were built, mainly to rent to the visitors. Fortunes were made (and lost) by landowners, speculative builders and architects. Indeed one the best architects to work in and for the city, Thomas Baldwin went bankrupt.

Beau Nash organised and presided over the fashionable throng while John Wood the Elder, scathing of the architecture put up before he settled in the city in the 1727, provided the architectural genius to turn a provincial city into a 'New Rome', possibly at the instigation of Ralph Allen who owned Bath stone quarries and was involved in moves to make the River Avon navigable to Bristol. He encouraged Wood 'to turn his Thoughts towards the Improvement of the City by Building'. In 1725, while still living in Yorkshire, Wood produced his first draft plan to develop land owned in the main by Robert Gay.

Wood started with Queen Square in 1728 where he designed each side as what became known as 'palace fronts'. This was an idea he probably copied from 1720 terraces in London's Grosvenor Square in which the terrace houses, usually three windows or bays wide, are built as if a vast palace facade with a centrepiece, usually pedimented and with the end houses treated as end pavilions. This rapidly became the norm, not only in Bath but elsewhere in England, and helped significantly in giving the townscape great dignity and coherence. He built the 'Grand Place of Assembly to be called the Royal Forum of Bath', now called, rather less grandiosely, North Parade and South Parade, and much else besides. His other great design was the King's Circus, now just called the Circus, which he had just started building when he died in May 1754. His son, also called John and born in Bath in 1727, took over to complete the Circus and designed that remarkable and unequalled tour de force, the Royal Crescent of 1767-74, probably the first crescent in England. The Woods also designed public buildings, the younger John the New Assembly Rooms and the Hot Bath, for example.

Sadly Wood the Younger died at the height of his powers and relatively young in 1781. However other architects and developers took up the palm, including Thomas Baldwin, Richard Eveleigh, John Palmer and, in the nineteenth century Henry Goodridge and John Brydon, The Georgian legacy is, however, what makes Bath great. It is very much one of the finest cities in England, if not in Europe.

I have known and visited Bath for over thirty years. I have looked down over the city from Bathampton Down and have walked the hills and valleys of the Avon and Midford Brook over the years and its architecture and townscape never cease to stun me.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Bath History in Photos

More Bath PhotosMore Bath history

What you are reading here about Bath are excerpts from our book Bath Photographic Memories by Martin Andrew, just one of our Photographic Memories books.