Worcester History

The history of Worcester and specially selected photographs

For over 2000 years there has been a settlement at Worcester, as numerous Iron Age finds indicate. It owes its origin to the River Severn, which was fordable at this point at low tide, making it the only crossing point between Gloucester and Bridgnorth, and therefore of both practical and strategic importance. A small farming community developed initially, and only attained a degree of prominence in the Roman period, after the 20th Legion built a road along the east bank of the Severn, linking forts at Kingsholm (Gloucester) and Wroxeter (near Shrewsbury). What was later to become Worcester lay on the route of the road and soon developed into a river port (possibly called Vertis) mainly for transporting salt brought from the mines at Droitwich.

Despite the beginnings of trade and commerce, Worcester's economy was still mainly agrarian, exploiting the fertile soils of the river terraces. However, in the 2nd century a major iron smelting industry developed, which seems to have begun in the Deansway/Broad Street area of the city, close to the river. Despite the importance of the iron smelting operations, Worcester was never in the first rank of Roman towns. But it does seem to have become a flourishing industrial and commercial centre which made good use of its rich agricultural hinterland. This probably ensured its survival in the years of instability which began in the late 3rd century. Worcester's growth was reversed and iron production ceased but, unlike many other settlements, it did survive continuing instability, Roman withdrawal in the 5th century and the remorseless spread of invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes across the country.

After the Romans left, a British community seems to have established control over Worcester until the 7th century, when it became part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the Hwicce, whose power base was at Winchcombe in Gloucestershire. In c680 Worcester acquired a cathedral dedicated to St Peter, and a bishop called Bosel. Weogornaceaster, as the Anglo-Saxons called the town, became an increasingly important religious centre, with the wealth of the church acting as a stimulus for commerce.

In the 890s Aethelred of Mercia refortified Worcester, which acquired earth walls and ditches, establishing it as a ‘burh’ (fortified borough) and administrative centre, and marking a significant step forward. It established the structure around which the later medieval town was to develop - a structure still visible in today's street plan. Bishop (later Saint) Oswald founded a monastic community of Benedictines for whom he built a new cathedral (next to St Peter's) dedicated to Christ and St Mary. Completed by 983, the site of Oswald's cathedral lies beneath the present building. Late Saxon Worcester had become a prosperous town, ecclesiastically important, with a valuable agricultural hinterland and an economy based on trade and local manufacturing, supplemented by taxes levied on river and road traffic passing through. Nevertheless, Viking raids into the Severn Valley must have added a touch of uncertainty to daily life, and on one memorable occasion in 1041, the Danish King Harthacnut tried to raise taxes from Worcester. The king's would-be tax collector was murdered by outraged citizens and his flayed skin nailed to the cathedral door (where traces of it remained for centuries). Harthacnut sent a retaliatory raiding party but the citizens took refuge on Bevere Island upriver and the Danes contented themselves with sacking the town and burning the cathedral before they left the area.

When the Normans arrived they found a well-established town with the foundations already laid for the important medieval city which was to develop. Under the leadership of Urse d'Abitot, Sheriff of Worcester from 1069, the Normans built a castle, of which no trace remains. Wulfstan, the Saxon bishop, was allowed to stay in office and rebuilt the cathedral between 1084 and 1089 on the site of St Mary's. Some fragments of his building still survive, notably the crypt. Respected by Saxons and Normans alike, Bishop (later Saint) Wulfstan had considerable influence and helped Worcester become the most important ecclesiastical centre in the West Midlands.

The 12th and 13th centuries were turbulent times for Worcester due to the endless squabblings between kings and nobles. The strategic nature of the river crossing meant everybody was keen to control it. The Civil War (1135-54) of King Stephen's reign was a particularly bad time, especially when the king captured and burnt the city, but it was only one of numerous conflicts throughout these two centuries. It is not surprising that substantial city walls were deemed necessary, and they were completed some time during King John's reign. Nevertheless, Worcester prospered: by the 14th century it had a cathedral, 11 churches and four monastic communities. Its suburbs were spreading north along Foregate Street and The Tything, east along Lowesmoor and south along Sidbury, while the suburb of St John's was taking shape across the river. In 1377 the population was 3,000; by the 16th century it had grown to 8,000. The community engaged in an enormous variety of trades and crafts and traded with France, Germany, Spain, Iceland and the Low Countries. Cloth and clothing manufacture came to dominate the economy in the 15th century and the city acquired an international reputation for its products.

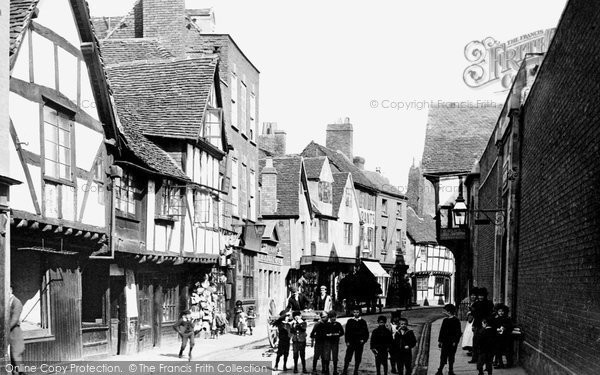

During the 16th and 17th centuries it began to look as though the good times were over. Other Severn Valley towns were eroding Worcester's regional dominance and the clothing industry was in decline. In 1637 the city was badly hit by plague, which killed perhaps one in ten of the population. And then came the Civil War: Worcester, strategically important as ever, found itself once more in the thick of the action. Both the first skirmish (1642) and the final battle (1651) were fought in or close to the city, and after Charles I's victory at Edgehill, Worcester became a Royalist garrison. In 1646 it withstood three months of siege before surrendering. During the siege some medieval suburbs were deliberately destroyed by the garrison to prevent the Parliamentarians approaching too close to the city walls. Further massive damage took place during the Battle of Worcester in 1651 and it is not surprising that the city has few surviving medieval buildings. Ordinary citizens must have been deeply resentful of both sides in the Civil War, but what was perceived as Worcester's staunch loyalty to the Stuart cause earned it the name Faithful City.

Despite the disruption and destruction, Worcester got back to business as soon as the fighting stopped. A 1661 census listed it as the 11th city of the kingdom and it flourished anew in the late 17th century, making good use of its position by the Severn. Indeed, it is hard to overstate the importance of the river in the city's history. Though its strategic significance often brought conflict, its principal role for most of its history has been a commercial one. By the end of the 17th century the Severn was busier than any other European river except the Meuse, and Worcester was one of its principal ports.

Superficially at least, Worcester prospered throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but this was deceptive. The city needed to diversify its manufacturing base and to improve its infrastructure, but it did neither. Too much of the population was still dependent on the declining clothing industry (particularly glove making) with its desperately low wages. All the money lavished by the wealthy on grand houses and churches could not altogether hide the fact that a huge underclass lived in great poverty in squalid slums. Some efforts were made to address the problem, particularly by local Whigs, and it was partly to reduce unemployment that in 1751 a group of businessmen founded the Worcester Porcelain Works. By 1788 a rival firm, Chamberlain & Co, had set up on Severn Street. In that same year George III, in town to enjoy the Three Choirs Festival, toured the Severn Street works and ordered three dinner services for the royal household. The company received the royal warrant in 1789 and the internationally renowned Royal Worcester, formed from a merger of the rivals, still operates from the same site today.

Severn trade was given a welcome boost by the growing canal system: the Droitwich Canal, the Staffordshire and Worcestershire, and the Worcester and Birmingham all played their part, but major improvements were needed on the river itself. Though the Severn was tidal up to Worcester, and navigable almost as far as Welshpool, the navigation had never been an easy one. Water levels were very low in summer and above Gloucester the river was little more than a series of pools separated by rock bars with minimal depth of water above them. In 1827 the completion of the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal boosted trade by enabling traffic on the lower Severn to bypass the river, but the opening of the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway in 1841 led to a reduction in canal traffic. It was only between 1842 and 1844 that the navigation of the upper Severn was at last improved. Locks and weirs were built, causing the upper tidal limit to move south to Gloucester, and the river was dredged. In 1890 further improvements were made to encourage larger vessels from the channel ports, but the river was losing out heavily to the railway, even though Worcester's rail links were, and remain, inadequate. The 20th century growth of road transport dealt the final blow, though it was 1961 before the last commercial cargo left Diglis Basin by narrowboat.

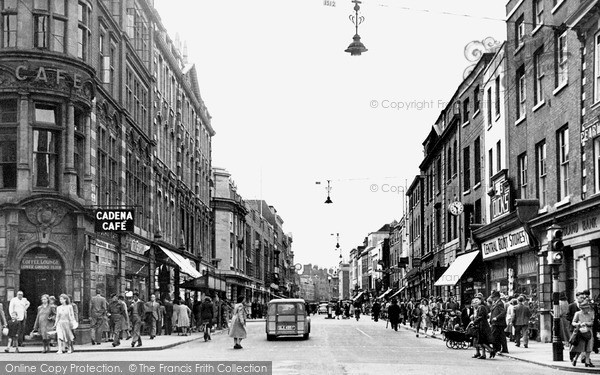

In 1826 the government abolished import duty on foreign gloves, a move which brought about the end of Worcester's gloving industry. Other industries sprang up, such as brewing, bottle making, vinegar production and engineering. Throughout the late 19th century conditions for the urban poor slowly began to improve, with increased provision of fresh water and better sanitation, though it was only in the 1920s that slum clearance began. Housing for the better off, however, expanded considerably through the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Later, in the 1960s, massive redevelopment of the city centre involved the wholesale demolition of most of the remaining ancient buildings, and the imposition of a brutal road system, cutting the cathedral off from High Street. It made Worcester a byword for how not to do things.

After the M5 replaced the Severn and the canals as a trading route, Worcester became important for distribution and light engineering and over the last two decades it has expanded again. In the centre an effort has been made to make further redevelopment more sympathetic to the historic fabric and some (though not nearly enough) of the 60s horrors have been swept away. Nothing can restore what has been lost; yet it is not all bad news. The medieval street pattern remains clearly visible, as do stretches of the city walls. The cathedral and the monastic ruins, together with Edgar Tower and the 15th-, 16th- and 17th-century buildings of Friar Street, New Street and Corn Market hint at the glory that was medieval Worcester. There is an abundance of elegant Georgian architecture and some good Victorian buildings too, of both the exuberant, flamboyant type and the solid, sensible variety. Despite all that has been lost, Worcester is still a rewarding city to explore and tourism is today playing an increasingly important part in its economy.

An added attraction is that every third year the city hosts Europe's oldest musical festival, the Three Choirs, which it has shared with Hereford and Gloucester since 1719. The music of Worcester's most famous son, Sir Edward Elgar, often features in the festival programme. Other tastes in music and the arts are well catered for, and sport is important too, with the bonus that the county cricket ground is generally agreed to be the most attractive in the country. The River Severn continues to play an important role, pleasure steamers sharing the water with canoes, dragon boats, cruisers and an abundance of narrowboats whose owners (or hirers) are now bent on pleasure, not commerce.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Worcester History in Photos

More Worcester PhotosMore Worcester history

What you are reading here about Worcester are excerpts from our book Worcester Photographic Memories by Julie Meech, just one of our Photographic Memories books.